Post contributed by Lisa Pruitt, Ph.D., Professor of History and Director, Graduate Program in Public History at Middle Tennessee State University, and a recent recipient of our History of Medicine Travel Grant.

What is your research project?

My project looks at the evolution over time of the concept of the “crippled child.” Of course, physically impaired children have always been present and in all societies. But in the mid-19th century US (a little earlier in Europe), reformers began to see physically disabled children of the impoverished and working classes as a social problem requiring both social and medical intervention. The word “crippled” began to show up in the names of charitable organizations and institutions in the 1860s; their numbers proliferated from the late 19th century to the mid-20th. In the early years, a “crippled child” was usually understood to be a child with a physical impairment, but “normal” intelligence, whose condition physicians and surgeons believed could be improved to the point of allowing the child to achieve economic self-sufficiency in adulthood. More severely impaired children were called “incurables” and were typically excluded from medical or surgical treatment and rehabilitation. The most common conditions that caused physical impairment in children were tuberculosis of the bones and joints, rickets (amongst the poorest classes), and congenital defects such as clubbed feet or congenital dislocation of the hip (now referred to as developmental dysplasia of the hip). Impairments resulting from polio began to increase after the turn of the twentieth century. With improvements in sanitation and the development of antibiotics and the polio vaccine, infectious disease became less significant as a cause of physical disability in children by the mid-20th century. At the same time, the emphasis on treating only those children who could be made self-sufficient began to fade. Charity organizations, like the Association for the Aid of Crippled Children in New York, were surpassed in importance by advocacy organizations such as the National Society for Crippled Children (now Easter Seals). By the 1950s, the medical and advocacy communities began to focus on conditions that earlier would have been considered “incurable” – notably, cerebral palsy, muscular dystrophy, and spina bifida.

What did you use from Duke’s History of Medicine Collections?

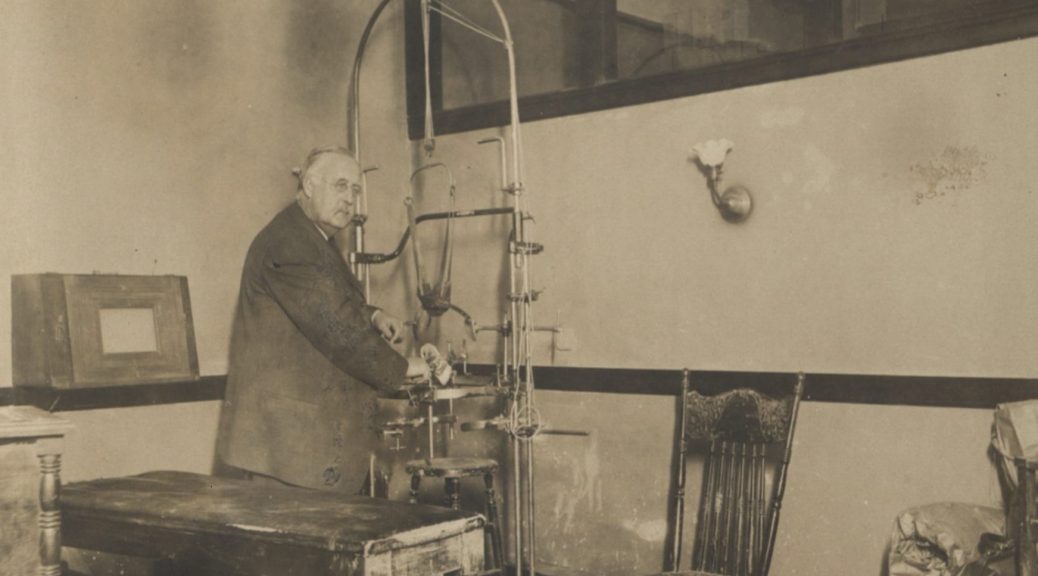

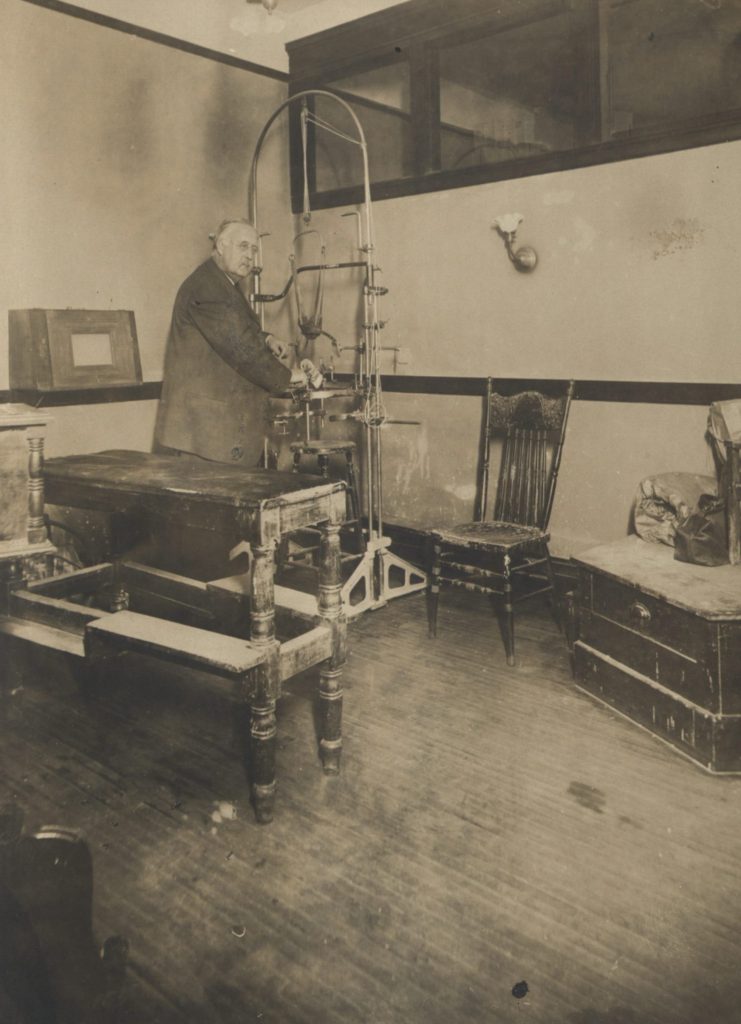

I used the John Ridlon Papers (1846-1936). Ridlon was a prominent orthopedic surgeon who spent his early career in New York in the 1890s and then practiced in Chicago in the early 20th century. I was drawn to his collection in hopes of learning more about the day-to-day work of orthopedic surgeons at that time and especially the impact of x-ray technology on their practice with children. I am also interested in the Home for Destitute Crippled Children in Chicago, with which Ridlon was heavily involved; I hoped I would find some information about that institution as well.

What surprised you or was unexpected?

I found more than I expected about a controversy in 1902-03 involving the highly publicized visit to the United States of Austrian orthopedic surgeon Adolf Lorenz. Lorenz claimed a very high success rate for his “bloodless” cure for congenital dislocation of the hip. In the fall of 1902, J. Ogden Armour (of the Armour meatpacking fortune) brought Lorenz to Chicago to treat his 5-year-old daughter, Lolita, who was born with bilateral dislocation of the hips. Until I accessed the collection, I did not realize that Lolita Armour had been Ridlon’s patient up until that time. Lorenz’s visit was hyped by the Hearst media empire and provoked a wildly enthusiastic response from the general public. American orthopedic surgeons, including Ridlon, were hostile in their responses to Lorenz.

I also did not expect to find such a rich vein of material about the early years of the American Orthopedic Association. Ridlon was a prominent member and corresponded extensively with other leaders of the profession. Early concerns and conflicts surface a lot in that correspondence. I did not have time to delve into this correspondence, but I highly recommend it for anyone interested in the professionalization of orthopedics.

One thing I learned about Ridlon’s practice that surprised me was its national scope. I wasn’t even looking for this information, but in the small amount of correspondence that I sifted through, I found that he had long-term patients in Oklahoma, New Mexico, Colorado, Montana, and (less surprisingly) Ohio. They traveled to see him, but I was surprised to find that he also traveled to them. Talk about house calls!

Anything else you’d like to share?

The Ridlon Papers are a rich resource. The correspondence is extensive. I was lucky that a separate folder on the Lorenz controversy had been created by Ridlon at some point, but I suspect that relevant correspondence is also scattered throughout the collection. Allow lots of time!

I found many interesting things in my research, but I’ll share one document that stood out to me. In this copy of one of his out-going letters from 1899, Ridlon comments on how an x-ray changed his diagnosis. The letter is 3 pages; he makes a humorous comment on the x-ray near the beginning.