Post contributed by Kaylee P. Alexander, Eleonore Jantz Reference Intern, 2020-2021

Man dies to live, and lives to die no more…until then, we eat cookies.

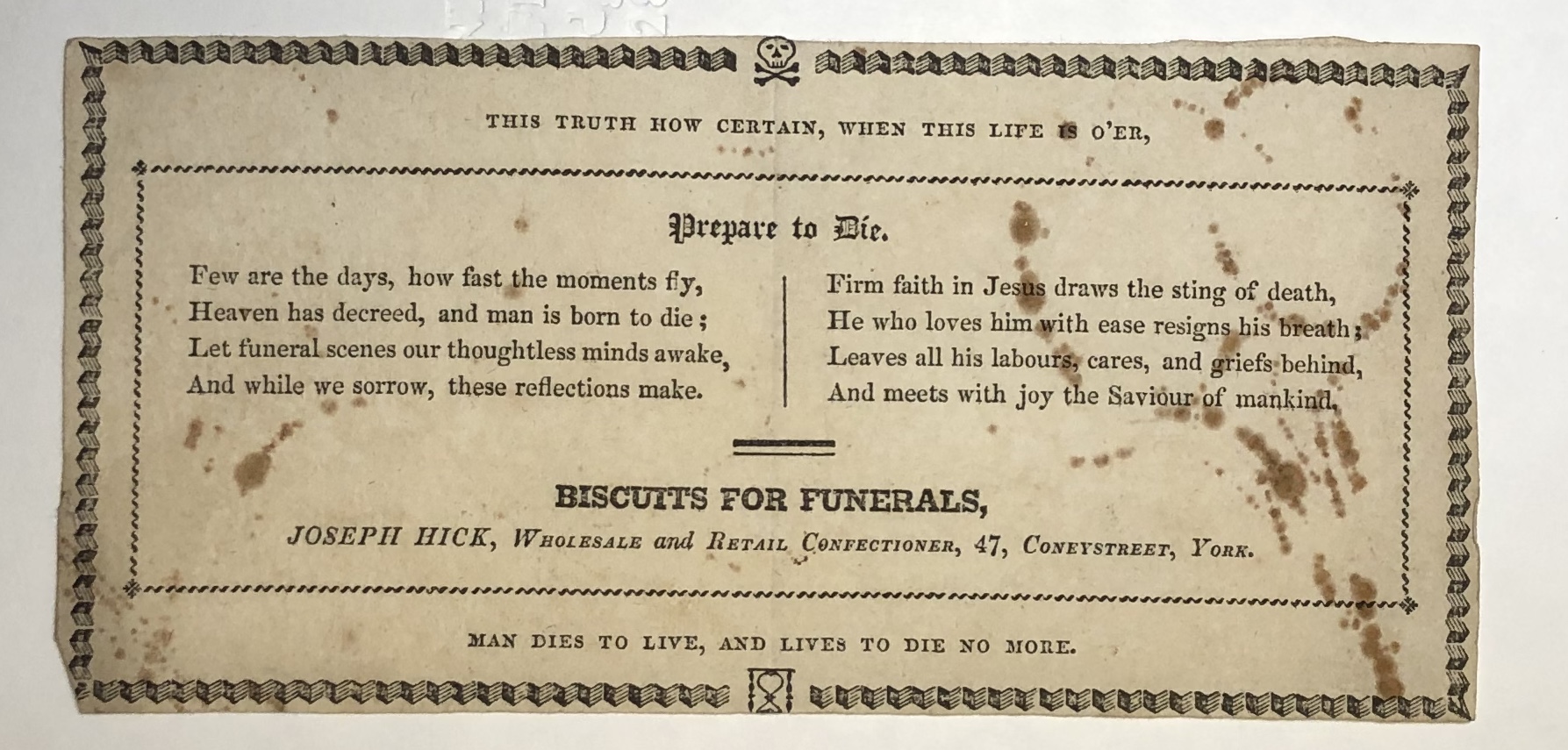

Tucked away in the Rubenstein Library’s box of memorial cards, ribbons, notices and ephemera in the Leona Bowman Carpenter Collection of English and American Literature is a lone advertisement for a curious confection: funeral biscuits. Imploring the reader to prepare for death, the ad suggests that one’s funerary arrangements simply cannot be complete without Hick’s biscuits.

Joseph Hick was a Yorkshire confectioner. In 1803, he had opened his first confectionery in partnership with Richard Kilner. In 1822, Kilner dissolved the partnership, leaving sole ownership to Hick, who relocated the business to 47 Coney Street. Hick operated his own confectionary until his death in 1860, when his estate and confectionery were left to his three children. Hick’s youngest daughter was Mary Ann Craven, the wife of Thomas Craven whose confectionery at 19 High Ousegate had been in operation since 1840. When Thomas died in 1862, Mary Ann was left in control of both confectioneries, which she merged and renamed M.A. Craven. In 1881, her son, Joseph William, joined the firm and the company was renamed M.A. Craven & Son.

With its thick black border, Hick’s advertisement mimics the design of early obituaries while inclusion of the elegy, “Prepare to Die,” hints towards the tradition of funeral cards. It is most likely, however, that the advertisement was intended to provide the reader with a sample design of what they might expect to encounter on the paper wrapper of Hick’s funeral biscuits.

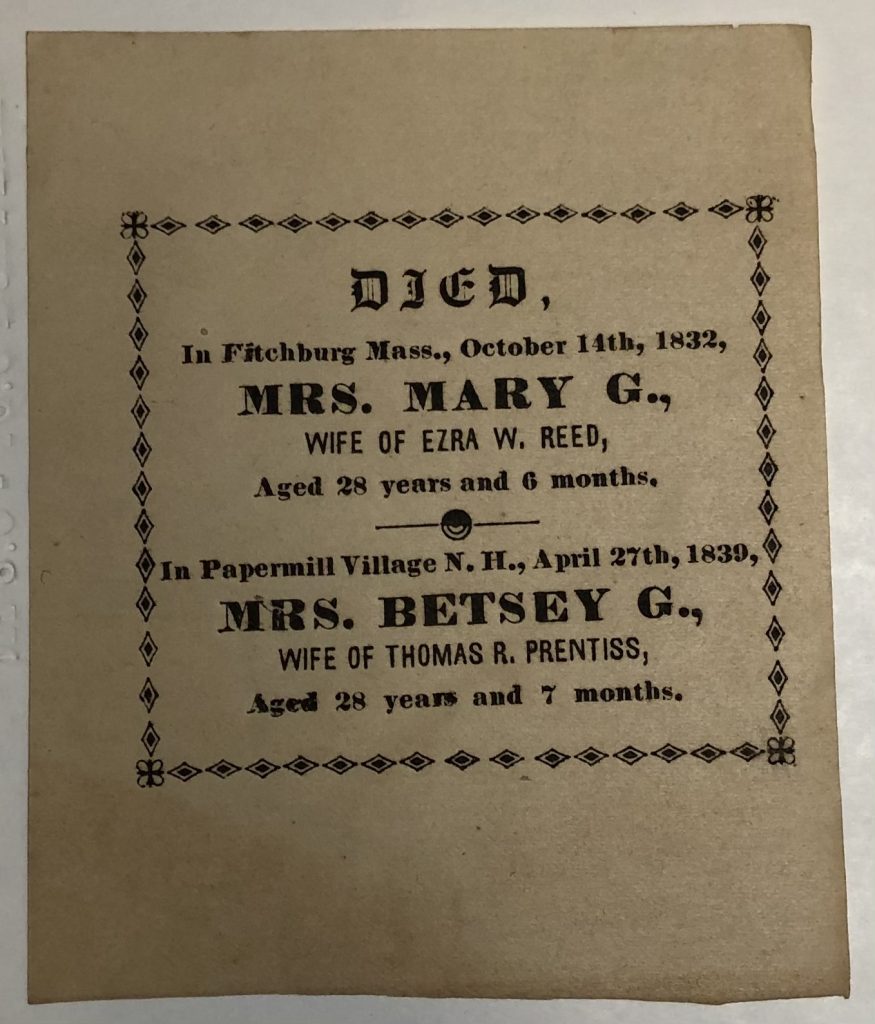

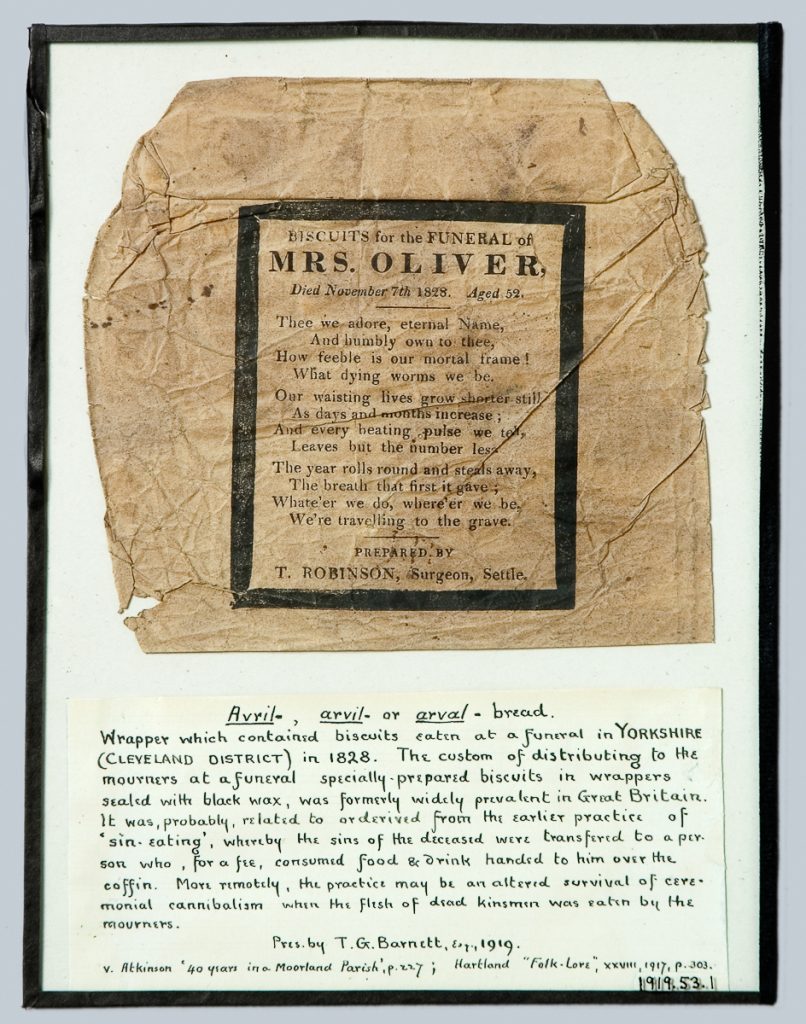

In nineteenth-century England—particularly in Yorkshire and Lancashire—it was customary to send funeral biscuits to the family and friends of the recently deceased. These confections would often be served with wine to funeral guests, and the wrappers, which frequently bore the name of the deceased, became souvenirs for those who had been in attendance. While the collecting of funeral tokens, from gloves to spoons, was commonplace well before the nineteenth century, the distribution and collection of funeral biscuit wrappers seems to most closely anticipate—in design, materials, and text—contemporary practices surrounding funeral cards.

The custom has typically been seen as a relic of Antique practices in which funerary banquets and offerings of wine and cakes for the dead were standard commemorative practices. The English tradition has also been likened to the Welsh practice of sin-eating, in which a designated sin-eater would consume a ritual meal, passed to him over the coffin, in order to absorb the sins of the deceased.

An 1896 text on English customs describes the use of funeral biscuits as follows:

At a funeral near Market Drayton in 1893, the body was brought downstairs, a short service was performed, and then glasses of wine and funeral biscuits were handed to each bearer across the coffin. The clergyman, who had lately come from Pembrokeshire, remarked that he was sorry to see that pagan custom still observed, and that he had put an end to it in his former cure. […] At Padiham wine and funeral biscuits are always given before the funeral, and the clergyman is always expected to go to the house, and hold a service before the funeral party goes to church. Arval bread is eat at funerals at Accrington, and there the guests are expected to put one shilling on the plate used for handing round the funeral biscuits. (Ditchfield, 202-203)

This tradition was not limited to the British Isles. Variants could also be found in other countries of Northern Europe, and was carried to the American colonies in the seventeenth century by the English and Dutch settlers. Here, the life of the funeral cookie lasted through the nineteenth century, before crumbling in the twentieth. The tradition lives one, however, in the passing out of funeral cards that, like the packing of the funeral biscuit, function as mementos of the deceased.

Though the original recipe(s) for funeral biscuits seem to have been lost to time, some have suggested that ginger or molasses cookies would have been the go-to flavors in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. So, if you’re, like me, interested in resurrecting this uncanny confection, check out these historical and contemporary recipes!

Selected References:

Paul Chrystal, Confectionery in Yorkshire Through Time (Gloucestershire: Amberley Publishing, 2009).

Margaret Coffin, Death in Early America: The History and Folklore of Customs and Superstitions of Early Medicine, Funerals, Burials, and Mourning (New York: Elsevier/Nelson Books, 1976).

H. Ditchfield. Old English Customs Extant at the Present Time: An Account of Local Observances, Festival Customs, and Ancient Ceremonies yet Surviving in Great Britain (London: George Redway, 1896).

Robin M. Jensen, “Dining with the Dead: From the Mensa to the Altar in Christian Late Antiquity,” in Commemorating the Dead: Texts and Artifacts in Context, Studies of Roman, Jewish, and Christian Burials, eds. Laurie Brink and Deborah Green (New York: Walter de Gruyter, 2008)

Summer Strevens, The Birth of The Chocolate City: Life in Georgian York (Gloucestershire: Amberley Publishing, 2014).

Is this article available in print form somewhere?

Thank you,

T. Crowder

Hi Thelma,

Unfortunately, no–these blog posts are shared online only. You are welcome to print a copy of the blog post, of course! Please let us know if we can help you get a copy of the post in any way.