Post contributed by Kelly Wooten, Librarian for the Sallie Bingham Center for Women’s History and Culture

In the fall 2018 semester, I worked with students in two sections of Dr. Amanda Wetsel’s Writing 101 course, Photography and Anthropology to introduce them to the Rubenstein Library’s collection of artists’ books.

As context, Dr. Wetsel shared that students in Photography and Anthropology consider how anthropologists have treated photographs both as an object of inquiry and a means of communicating their findings. She writes, “As they read both early and contemporary anthropological texts, students think about multiple ways words and images interact. They then conduct ethnographic research on a photographic genre here at Duke, such as lock screen photographs, Instagram accounts, and displays of photos in dorm rooms.” As a final project, several students used the format of an artists’ book to convey their findings with words and photographs.

After their research visit, Dr. Wetsel reflected on how the works the students explored during their session inspired them to think creatively about their own projects:

Viewing artists’ books at the Rubenstein prompted students to think about how the form of a book can reflect its content, how to create powerful texts and format those texts creatively, and ways of making books engaging. As they unfolded the game board of Julie Chen’s A Guide to Higher Learning, stretched Ed Ruscha’s Every Building on the Sunset Strip across the table, tugged down the staircase-like accordion folds of text on Clarissa Sligh’s What’s Happening with Momma and unrolled the delicate, cigarette-shaped scrolls of Amy Pirkle’s Smoke, students thought about how they could adapt the forms to communicate their own research. We’re fortunate to have a range of creative and beautiful artists’ books at the Rubenstein for students to touch, read, and use as inspiration. The form of the artists’ book allowed the students to combine text and photos in powerful and unexpected ways.

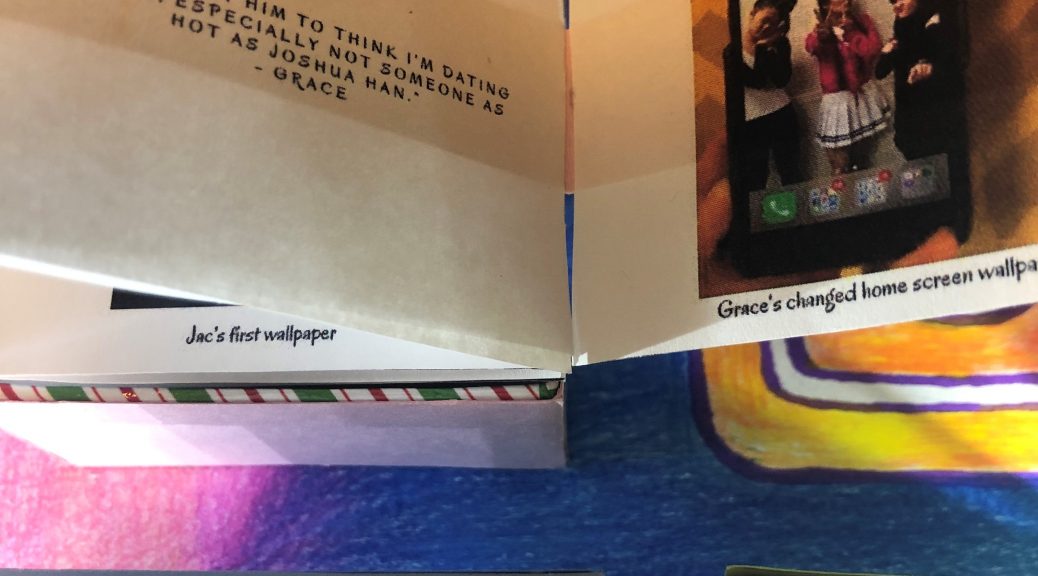

Joanne Kim, ’22, created a book entitled A View into the Wallpaper. The book itself resembles a cell phone, a box which opens to reveal four smaller icon-shaped boxes. She writes:

The transition from home to college life is a daunting change which necessitates adaptation and the reconciliation of homesickness, and in some cases, existentialism. At Duke University, freshmen female and male students handle change differently. Female students respond by physically displaying the change in spaces such as their cellphone lock and home screen wallpaper. Male students seek some consistency in a major time of change, and therefore, keep their lock and home screen wallpapers the same through the transition. All the while, both genders utilize the space as a means of protecting and discovering their core identities throughout their freshman year and beyond.

Joshua Li, ’22, describes his piece Lily as having “six long and blue trapezoidal flaps with a Rubik’s cube at the center.” Each flap as an image of a meme which he presents as a form of community building, and the cube can be removed and played with separately. He shared a quote from the text in the book:

Memes function like a societal adhesive, a catalyst for unity in the ultra-diverse Duke community, as these witty photographs have for many years brought people together through shared laughter and warmth. Similar to how creating and looking at memes promote harmony, solving a Rubik’s cube enables one to achieve that same sense of harmony by restoring order to the scrambled and disorganized faces of the cube.

He titled his book Lily “not only because the end product looked like the flower, but also because in Chinese culture lilies symbolize harmony and unity, which was the main conclusion from my research.” He continues, “The fact that the meme cube is at the center of a display made up of Duke colors (or close to Duke colors – the 3D printers here don’t bleed Duke Blue and white apparently) emphasizes the theme of memes being at the center of Duke University.”