A broadside is a single-sheet notice or advertisement, often textual rather than pictorial. The historical type of broadsides called ephemera (the Latin word, inherited from Greek, referred to things that do not last long) are temporary documents created for a specific purpose and intended to be thrown away.

The Broadsides and Ephemera Collection (David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Duke University) captures written and printed materials of widespread and short-lived use; items, such as event announcements, letters, tickets, posters, social notices, or printouts on current political affairs whose impact was not meant to sustain the test of time. These are the materials that I want to bring to your attention.

The collection includes items from more than 28 countries. The material is quite heterogeneous in terms of content and historical periods. From the Viceroyalty of Peru, to the tensions between Japanese and American soldiers in the early 1940s in the Philippines, one feels a bit like a time traveler without much of a compass, navigating across a sea of material of daunting complexity. After the first scroll through the many rows and tabs in the collection’s Excel sheet, I began questioning, amidst gallons of coffee, the romantic view of the cataloging librarian as a detective of knowledge long lost. Voltaire’s words at the beginning of The Age of Louis XIV regained strength: “Not everything that is done deserves recording”.

Yet, as I delved deeper into the collection, I quickly discovered that Ephemera provides a unique window to understand much about the working of human communities all over the world. In fact, the range of common themes emerging is sort of striking given its geographical and temporal scope. It is actually fun. Let me focus on three themes that consistently emerge across the different sections of the international broadsides.

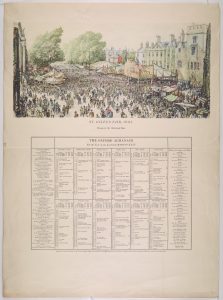

Ephemera work first as a record of the basic organization of social communities. In these instances art becomes a tool to highlight key moments in the everyday life of very diverse communities. The contrast between the 1932 poster for the “Feria de Abril” in Seville, Spain and the 1946 University of Oxford’s Almanac is very telling in this regard. The former serves to mark the most important week in any given year in Seville’s life: around Easter, the city turns into a mixture of art, devotion, and excess in a perfectly balanced and stratified way (different sectors, businesses and social classes get together to party at night after taking part in the parades or processions thanking and honoring the patrons/matrons of the different churches in the city).

The Almanac provides a list of the head of colleges and the university calendar, making public the key milestones in the life of the university. While the purpose and activities highlighted by these two items could not be more different, their basic function is the same. Both convey useful knowledge about the life of two cities driven by very different pursuits. I know where I would rather study, but it is also quite clear where one ought to go to have some real fun.

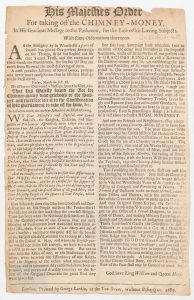

A second function of the sort of items included in the international broadsides is to offer a glimpse of political and social relations in many different places. The records on England, for instance, include a letter from subjects to the new King, William of Orange, thanking him for the removal of a the “hearth tax” in 1689, or a piece capturing neatly the scope and goals of the chartist movement in their quest for universal male suffrage, the secret ballot, and annual Parliament elections among other things.

The contrast between these two documents (William of Orange order for taking off the Chimney-Money, and the Birmingham Reform Petition) captures nicely the road traveled in England from the Glorious Revolution at the end of the 17th century, to the forefront of economic and political modernization in the 19th century, when the Chartism took place.

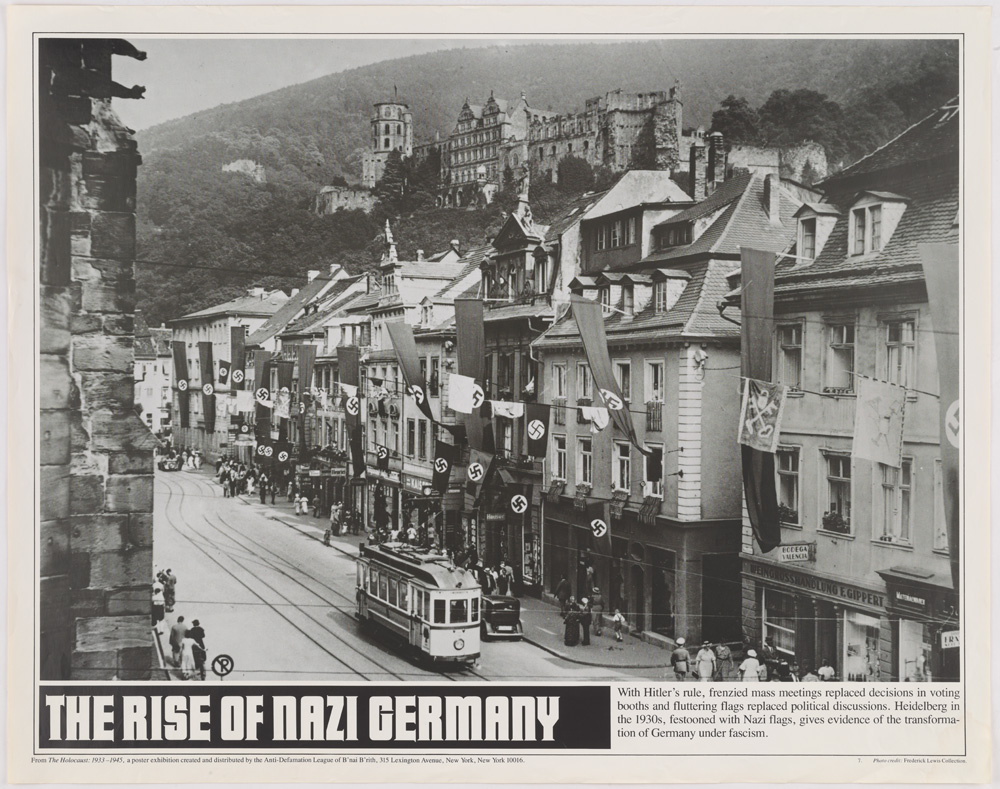

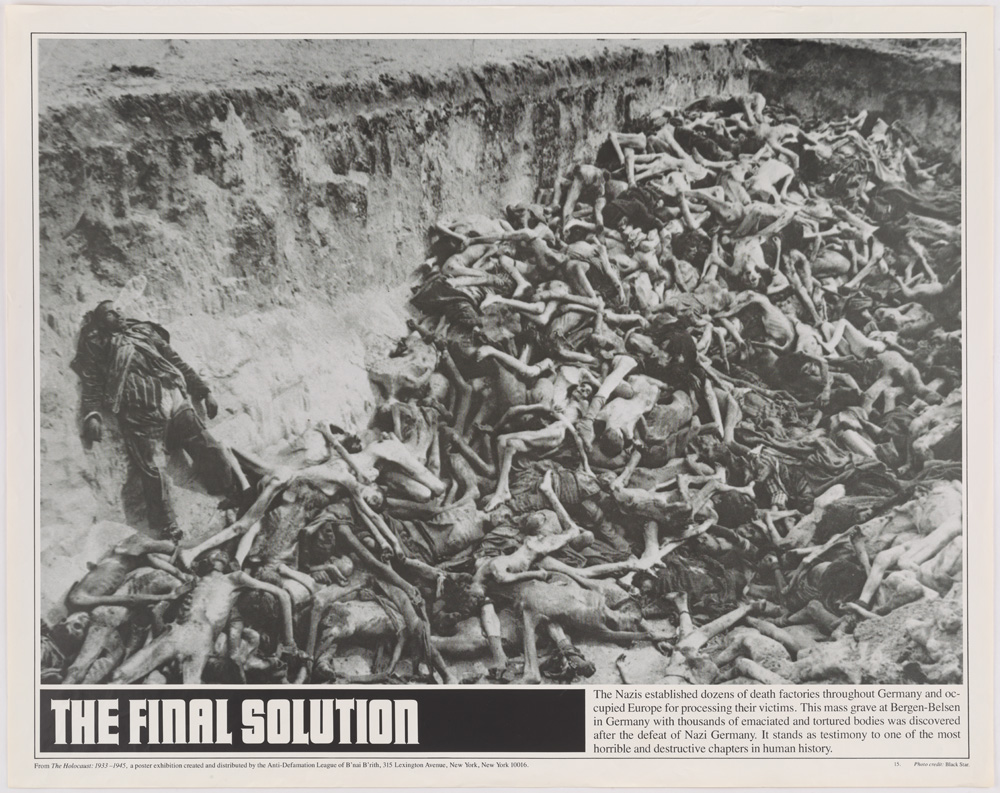

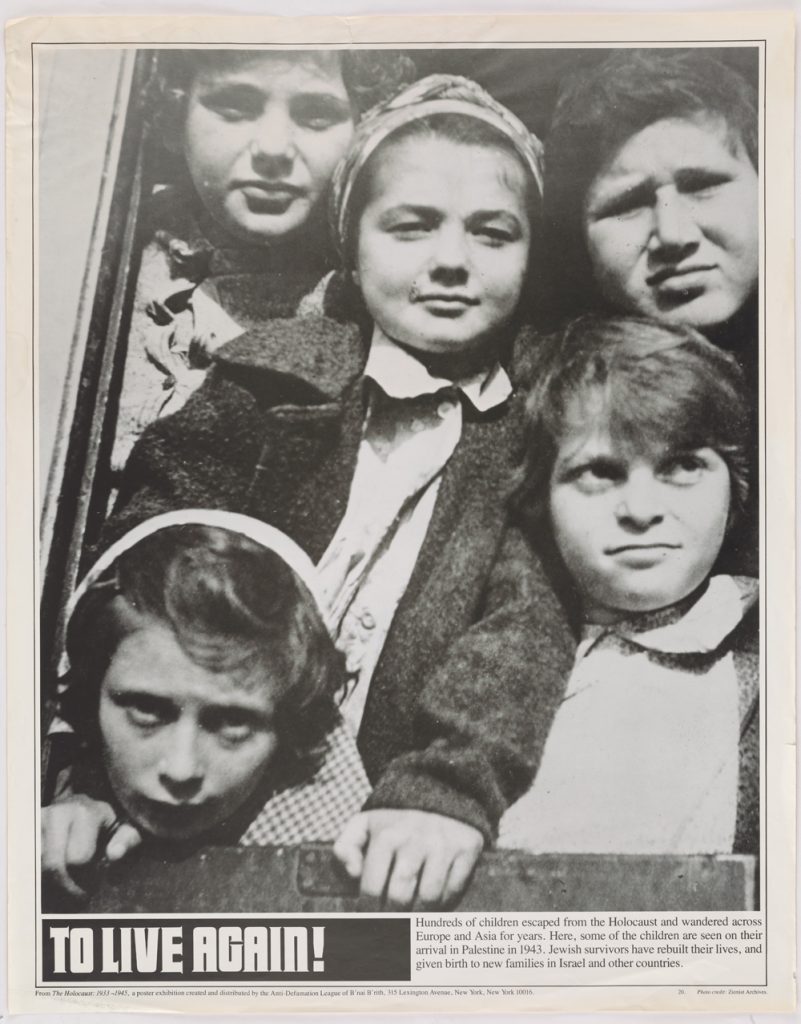

On a grimmer note, the records on Germany capture effectively the rise of the National Socialist German Workers’ Party (commonly referred to in English as the Nazi Party) in the interwar period in cities like Heidelberg, and the consequences that ensued in terms of mass casualties for ones or exile for others.

But the richest and most comprehensive theme that gives coherence to the records across different countries is the one of war and political persuasion/propaganda. Persuasion comes in very different forms. It can be intellectually driven and directed to small circles: the English records feature letters from American activists to English political philosophers such as John Stuart Mill in a quest for support for the anti-slavery movement. Or it can be emotionally driven and directed to broad populations. It is in this particular variety of ephemera where Duke’s International Broadsides Collection really shines.

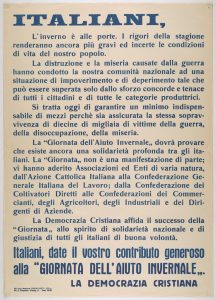

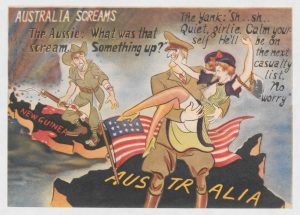

The records contain dozens of art manifestations from pro-Axis actors in Italy, Germany, and Japan, as well as efforts from the British and U.S. armies to undermine the morale and support of Japanese troops in the Philippines after 1945. Among the former, who knew that the motto of House Stark in Game of Thrones (Winter is coming) was to be found in a piece of political propaganda from Italian fascists against the Allies? Or that Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s virtuous smile was wider the more missiles fell on the Italian cities? Or that the good children of Italy were at risk of being pulled apart by the three evils of Communism, Judaism and Freemasonry? Or that the Australian soldiers would do better to return home to protect their women from the American soldiers’ predatory behavior?

Finally, another good example is this tricky Japanese leaflet. At first, it appears to show just an soldier and his wife embracing under the beautiful moon, but when it is unfolded, although we can still see the soldier’s undamaged legs, we see that he is dead on the battlefield near a barbed wire.

Regardless of their goals, values, and motives, and our views about them, it is remarkable to observe how all parties involved use popular forms of art and imagery to appeal to their constituencies’ worst fears and prejudices about the other and to present themselves as the more humane side.

As you can see there is much to learn and enjoy by delving in collections such as the international broadsides. Along the process, the metadata librarian confronts an important trade-off between efficiency and usefulness, between speed in processing and detail in the amount of information provided for the prospective user. If we want the collection to be useful for students and scholars, it is necessary to provide a minimum of contextual information for them to be able to locate each item and make the best of it. Yet in many instances this proves a challenging task, one that may well require hours, if not days, of digging into every possible angle that may prove helpful. At the extreme, this is bound to pose too much of a burden in terms of processing time. At this point, I do not have a magic formula to balance this trade-off but I tend to lean on the side of providing as much detail as required for a proper understanding of each piece. Otherwise, the digitally processed item will fail to meet Voltaire’s criteria for what deserves to be recorded. A record in a vacuum, whether in bites or ink, hardly allows users to appreciate those “little things” that, as Conan Doyle’s axiom has it, “are infinitely the most important”.