Recently, while reading the fascinating oral history of ‘60s girl groups, ‘But Will You Love Me Tomorrow?’, I was quite taken by a brief chapter on The Shirelles concerning a monumental concert fundraiser in Alabama that has largely been forgotten. As the Summer heat bears down this Juneteenth, let’s take a look back at Salute to Freedom ’63 for this installment of Insist!

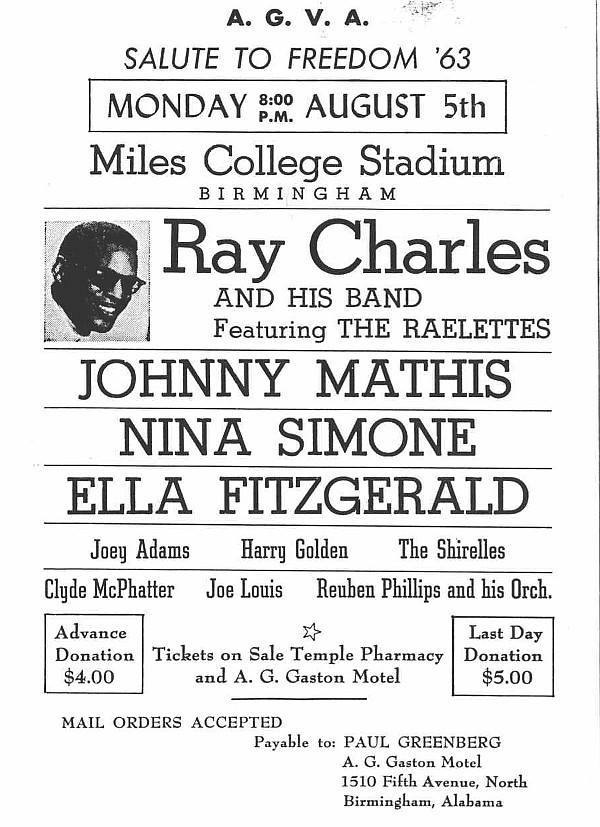

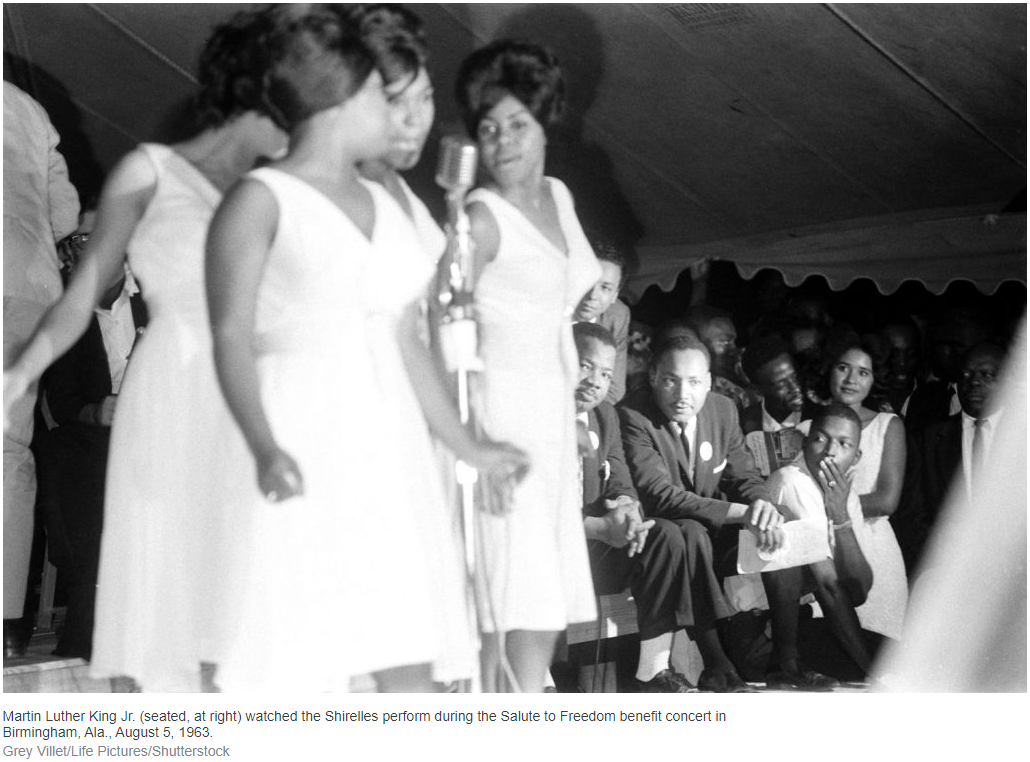

Birmingham, Alabama, August 5th, 1963. In a city and time rife with tension and conflict, only two weeks from city segregation ordinances being repealed, and only months since the Birmingham Campaign for civil rights, the Salute to Freedom event was a major happening and endeavor. One of many events put on by national civil rights organizations as fundraisers for the upcoming March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, the Birmingham event was absurdly laden with talent and prominence. Martin Luther King, Jr (then head of SCLC) and James Baldwin were there, along with Joe Louis and Dick Gregory. And included on the musical slate, none other than Ray Charles, Nina Simone, Johnny Mathis, Clyde McPhatter, the Shirelles and Ella Fitzgerald (though it isn’t clear if she actually performed).

With an event of this stature, and with divisions in the area so stark, attendance and interest and scrutiny were sure to be high. Local press and authorities effectively ignored and stonewalled the event, while volunteers drummed up promotion and ticket sales. Initially planned for the large auditorium downtown, permission was denied at the last minute, forcing the event to be held five miles out of town on the football field at Miles College, on a makeshift stage. Only one major hotel would allow attendees as guests. Cab drivers refused service. Birmingham police wouldn’t work the show. Even still, the event was able to occur, on a 98 degree day, with upwards of 16,000 attending, many even walking miles with their own chairs.

Salute to Freedom ‘63 ran late into the evening, and at one point during Johnny Mathis’s performance, the rickety stage partially gave way, injuring several people onstage. The show carried on but the difficulties were far from over. The performers, who were traveling together on a chartered plan from New York, were delayed several hours returning due to a bomb threat at the airport. National press barely covered the event, with the old gray lady only running four lines about it, primarily concerning the stage collapse. Though never published, there are thankfully a few terrific photos courtesy of LIFE magazine: March on Washington: Rare Photos of a Star-Studded Fundraiser, 1963.

Just over three weeks later, on August 28th, was the March on Washington. Then only a couple of weeks later, on September 15th, Ku Klux Klan members bombed the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, killing four young girls. John Coltrane composed his stunning ‘Alabama’ in response to the bombing. We’ll conclude this Insist post with a live clip of the tune:

Thanks Christina Manzella for

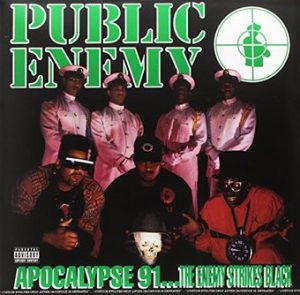

Thanks Christina Manzella for  No strangers to controversy and militant political statements, Public Enemy ratcheted up their rage even higher with their fourth album

No strangers to controversy and militant political statements, Public Enemy ratcheted up their rage even higher with their fourth album  Mos Def and Slick Rick are both hip hop legends, and well represented on the box, but this oddball (maybe not that odd, as Mos Def and Talib Kweli did a version of Slick Rick’s ‘Children’s Story’ on their

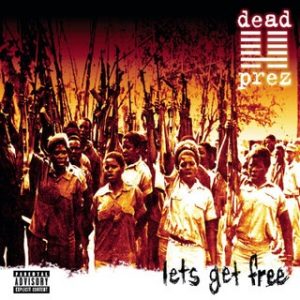

Mos Def and Slick Rick are both hip hop legends, and well represented on the box, but this oddball (maybe not that odd, as Mos Def and Talib Kweli did a version of Slick Rick’s ‘Children’s Story’ on their  No other modern hip-hop group is so consistently and unrelentingly political as Dead Prez (okay, sure, The Coup takes that crown) and one of their toughest tracks is ‘Police State’ from their 2000 debut ‘Let’s Get Free’. There’s no shortage of police commentary content to choose from (for starters see the anthology-included ‘

No other modern hip-hop group is so consistently and unrelentingly political as Dead Prez (okay, sure, The Coup takes that crown) and one of their toughest tracks is ‘Police State’ from their 2000 debut ‘Let’s Get Free’. There’s no shortage of police commentary content to choose from (for starters see the anthology-included ‘ The final album I want to address in this post is my personal favorite, her 2016 EP Coconut Oil. While her earlier and, tragically, lesser-known music spoke of struggle—both personal and more broadly—this six-track EP exudes joy in its reminder to take care of ourselves. In “Scuse Me” and “Coconut Oil,” we find self-love anthems. With lyrics like “I don’t need a crown to know that I’m a queen” in the former and “Don’t worry ’bout the small things, I know I can do all things” in the latter, Lizzo exudes a sort of self-assuredness toward which we all strive. Furthermore, she stresses that, if we can love ourselves, then we know just how deserving of others’ love we are, as illustrated in the lyrics of “Worship” and her first big single, “Good as Hell.” Activism, whether it entails fighting for the collective or for oneself, is exhausting. This EP provides us with that brief break necessary to avoid burnout and to practice a little self-care.

The final album I want to address in this post is my personal favorite, her 2016 EP Coconut Oil. While her earlier and, tragically, lesser-known music spoke of struggle—both personal and more broadly—this six-track EP exudes joy in its reminder to take care of ourselves. In “Scuse Me” and “Coconut Oil,” we find self-love anthems. With lyrics like “I don’t need a crown to know that I’m a queen” in the former and “Don’t worry ’bout the small things, I know I can do all things” in the latter, Lizzo exudes a sort of self-assuredness toward which we all strive. Furthermore, she stresses that, if we can love ourselves, then we know just how deserving of others’ love we are, as illustrated in the lyrics of “Worship” and her first big single, “Good as Hell.” Activism, whether it entails fighting for the collective or for oneself, is exhausting. This EP provides us with that brief break necessary to avoid burnout and to practice a little self-care. Recorded primarily at JazzFest Berlin in 2019, the festival and experience of being in Germany presented her and the band with a series of stressors and slights that very much played out in the band’s confrontational performance that November night. The recording is also bookended with field recordings (set to music) of her giving a hotel staffer the what-for and of comments from her appearance on a panel discussion during the festival.

Recorded primarily at JazzFest Berlin in 2019, the festival and experience of being in Germany presented her and the band with a series of stressors and slights that very much played out in the band’s confrontational performance that November night. The recording is also bookended with field recordings (set to music) of her giving a hotel staffer the what-for and of comments from her appearance on a panel discussion during the festival.