by Laura Micham, Merle Hoffman Director, Sallie Bingham Center for Women’s History and Culture, and Meg Brown, E. Rhodes and Leona B. Carpenter Foundation Exhibits Librarian

August 2020 marked the centenary of the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment enfranchising many American women after nearly eighty years of activism. In order to explore the complexities and strategies of the American women’s suffrage movement, students in Duke’s Fall 2019 “Women in the Economy” course examined materials in the Rubenstein Library and then created the exhibition, Beyond Supply and Demand: Duke Economics Students Present 100 Years of American Women’s Suffrage.

One of the biggest challenges for the students was that the full range of contributions to the American women’s suffrage movement is not represented in the Rubenstein Library’s collections, or in the historical record generally. The dominant narrative of the movement, like the historical record of it, has focused on white women who benefited from the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment and neglected the contributions and struggles of Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC). Nevertheless we—students and librarians—tried throughout this exhibit to present a diversity of historical figures and viewpoints.

Because the idea for the suffrage movement began at an anti-slavery conference and borrowed much of its methodology from the abolition movement, it made sense to begin the exhibition there with the first of the ten themes students researched, “Abolition, Racism, and Resistance.” It was equally important to look at all of the themes through the lens of race and resistance because, though much of the current and historical narrative around the suffrage movement has focused on its white leaders, every dimension of the fight for the vote involved BIPOC communities.

For example, BIPOC such as Frances Ellen Watkins Harper, an abolitionist, suffragist, temperance leader, and one of the first African-American women to publish a novel (Iola Leroy, or, Shadows Uplifted, Garrigues Brothers, 1893), fought for human rights through their work in women’s clubs and churches in addition to suffrage organizations. Harper spoke at suffrage conventions in the nineteenth century and often clashed with white leaders. She adamantly believed in acknowledging the racism faced by Black people and how that could not be separated from the struggle for equality, including within the suffrage movement. At the same time, white suffragists and anti-suffragists upheld racist arguments, often dividing the movement and excluding BIPOC.

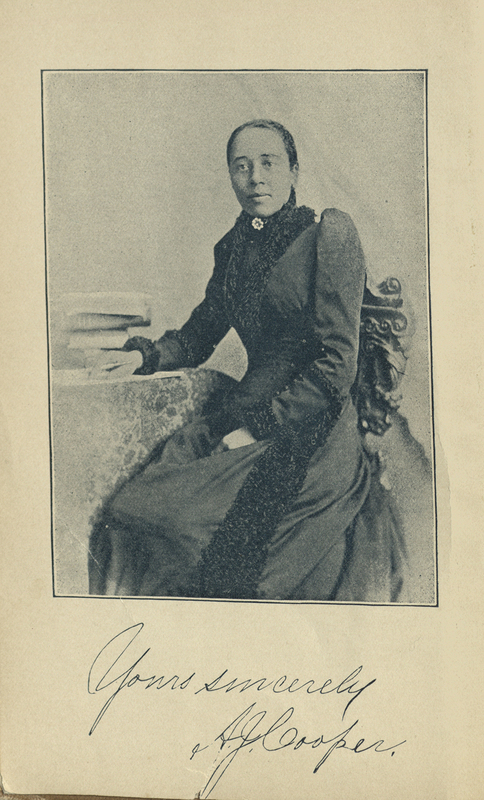

As the exhibit illustrates in almost every section, BIPOC suffragists were not deterred. For example, in the “Bible as a Tool,” religious leader, educator, and activist Nannie Helen Burroughs advocated for civil rights and voting rights for Black people, citing the lack of Christian values in discrimination and segregation and the moral importance of voting. Anna Julia Cooper, along with her groundbreaking volume A Voice From the South (Aldine Printing House, 1892), are featured in the “Regional Realities” section. Considered to be one of the first published articulations of black feminism, Cooper analyzes African American women’s realities facing racism, sexism, economic oppression, and lack of voting rights. This book was an especially powerful statement in a region of the country where most white pro- and anti-suffragists centered their campaigns on the preservation of white supremacy.

The final section of the exhibit, “The Long Tail of Voting Rights,” shows the continued conversation around women’s rights and voting rights after the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment. After 1920, there were invigorated movements to educate and mobilize new women voters, and to fight against voter suppression tactics like literacy laws and intimidation at the polls that disproportionately disenfranchised Black, Indigenous, and People of Color. One of the leaders of these movements was Fannie Lou Hamer who, having personally experienced literacy tests and poll tax requirements, became a field secretary for voter registration and welfare programs with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). In this role and as leader of the Freedom Democratic Party, she helped and encouraged thousands of African Americans to become registered voters. In her 1971 speech which she titled “Nobody’s Free Until Everybody’s Free,” she told the National Women’s Political Caucus in Washington that Black and white women had to work together toward freedom for all.

Dr. Genna Miller, the faculty member who taught the class, observed:

“The learning that went on during the exhibit project went beyond just the names and dates related to the suffrage movement. Students learned research methods and critical thinking skills. Students embraced the opportunity to examine and interpret historical documents written by labor activists, journalists, political and social reformers, and others who offered diverse lenses through which to consider and understand the significance of women’s suffrage, and the vast array of issues that the movement encompassed. Participating in this project with my students and the library staff has been an amazing experience. This could only happen at Duke!”