Post contributed by Mattison Bond, Project Research and Outreach Associate, John Hope Franklin Research Center

Highlighting Oral Histories by State Part 3

We at the John Hope Franklin Research Center are back again with another blog post to highlight some of the unique oral histories that can be found in the Behind the Veil Digital Collection. Last week’s post featured interviews from folks from Georgia, Illinois, Kentucky. This week, we take a deeper look into the collection by focusing on the interesting items that can be found from Kansas, Louisiana, Michigan.

You can view Part 2 of this series here: Digging through the Tapes: Exploring the Behind the Veil Collection Pt. 2 – The Devil’s Tale (duke.edu)

Enjoy exploring!!

Kansas

There is only one oral history that falls under the Kansas location tag. This oral history belongs to Ulysses Marshall, factory worker and sharecropper. Marshall was born and raised in St. Louis Missouri until he turned thirteen when his family moved southward to Fargo, Arkansas. When asked about his experience in Fargo, Marshall simply states, “It was bad.” This same sentiment would be repeated throughout the oral history as Marshall recalls his experience living within the South during Jim Crow.

When recalling his first experience with racism:

Part 1, 14:23 “I was pointing at this here White man. It was something I was pointing to, because I was trying to show my mother and father about it, and my daddy, he knows that could be an offense to point at the White man. That was a bad thing, because he may even think you was talking or making fun of him. He said, “Don’t do that. Don’t never do that. Don’t point at that man,” or something like that. “You could get us all in trouble.” It was just that bad.”

Or when describing police brutality: “Brutalities were bad. Bad. Real bad”

And even when he was recalling his experience as a Navy man:

Part 1, 32:17 “Well, yeah, they would about the prejudices, the hatred, and stuff like that. And this is one reason I couldn’t make a career out of it. Some of them made a career out of it. I said it wasn’t much freedom back here, but it wasn’t no freedom at all, back there, because to me, it was just you’re confined in a prison or something like that. It was just completely, totally discrimination, during that time. So that’s why I got out, and I could never see—well, they tell me the Army was a little better, but it was bad, because my brother, he retired from the Army and he was telling me some of the experiences that he went through, something like that. But they was bad, real bad.”

Marshall would end up in Kansas for the same reason that his father would leave St. Louis, Missouri, in search for work. After a long search for work in California with no success, Marshall would find work at a steel mill in Gary, Indiana. He would then be laid off that would lead to him finding work in Kansas at an airplane factory, where he would retire from.

The oral history of Ulysses Marshall may be bleak to most that take the time to listen to it. His life, filled with struggle and constant racism since moving South, is a reflection and example of the horrors that Jim Crow inflicted on the lives of everyday African Americans. But, as with many of the accounts within the collection, Marshall is still able to leave listeners with true and encouraging words. Interviewer Paul Ortiz would ask Marshall, what was it that “kept [him] going and striving through all the difficult” moments. Marshall, inspired by President Floyd Brown, founder of the Fargo Agricultural School would respond:

Part 2, 9:02 “I got a lot of inspiration from President Brown. Like he said, like his motto used, “work will win,” and to me, I’m a stronger believer in that. I think if a person wants something bad enough and go ahead to work and pursue it, I think he can accomplish. I think a man could reach about any goal that he strive for if he go—you got to put something into it because nothing going to come there and fall in your lap. I mean, if somebody think that, they just fooling theyself. So I kind of like that motto, “work will win.

You can listen to the oral history of Ulysses Marshall here: Ulysses Marshall interview recording, 1995 July 15 / Behind the Veil / Duke Digital Repository

Louisiana

The Louisiana location filter is the second largest in the collection, with a total of 138 items. When looking for a unique story in this part of the collection, the easiest option would be choosing the oral history of the only cytologist. Michael Gourrier was born and raised in New Orleans. He moved to Columbus, Ohio in 1962 to go to graduate school and then to Indianapolis. It was not until 1969 that he moved to Texas to work as a laboratory supervisor for the United States Public Health Service.

Interestingly enough, listeners do not learn this information, or much information about this particular occupation until closer to the end of the interview. Gourrier’s oral history focuses more on the history and contributions of African Americans to music, particularly Jazz. His early exposure to all types of music would set the tone and theme of the oral history as one of the first questions he answers is how Jim Crow shaped his life, and the music scene of New Orleans.

Part 1, 8:56 “New Orleans was a segregated society to an extent. It still is today. But from my perspective, music is a language that transcends all races, ethnic backgrounds and laws, whether legal or illegal…. Well, the other areas of activity around the city as far as the housing and the general accommodations and all, they might not have been able to live up to that particular adage. But as far as music is concerned, I think that it is definitely one of that you could say was really separate but equal, if not better.”

Within the interview, Gourrier provides listeners with a comprehensive history of race relations both outside and inside the music scene of New Orleans. While he believes that “Music has no color. I mean, it’s not black, it’s not white, it’s not red, it’s not green,” he acknowledges that Jim Crow laws significantly influenced the development of musicians, particularly in the South.

Part 1 31:51 “… the backwardness of the South, they were always behind and they were just slow in evolving. And then because of the segregation, Blacks were extra slow in being exposed and afforded the opportunity to be involved in this particular aspect. So I think this was one of the big factors as far as why everything here was, and shall we say, a later stage of development than it were other places. Because I mean, if you go back and you look at the period called the Harlem Renaissance. What were we doing down here? I guess you could say we were just one step past the menstrual shows during that particular period down here”

Gourrier’s passion for educating and sharing his love for Jazz would grow throughout time. He even mentions that after he retires, he hopes to become a jazz historian. Still alive today, he is better known as Mr. Jazz, radio host of WRIR-FM RDIO in Richmond, Virginia.

You can learn more about Michael Gourrier here: Michael Gourrier interview recording, 1994 August 04 / Behind the Veil / Duke Digital Repository

Michigan

The Michigan location filter has only two oral histories. Both interviews were conducted in two different cities and while each is unique, one stands out for several reasons. Alex Byrd, the interviewer of both oral histories had the pleasure of interviewing his own father, Sanford Byrd!

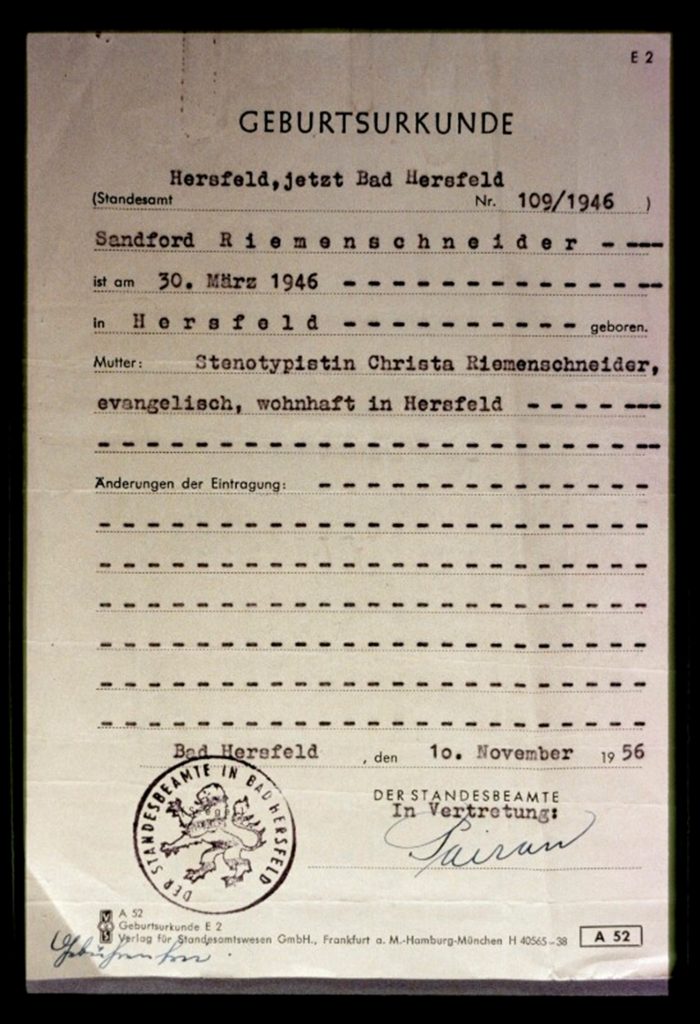

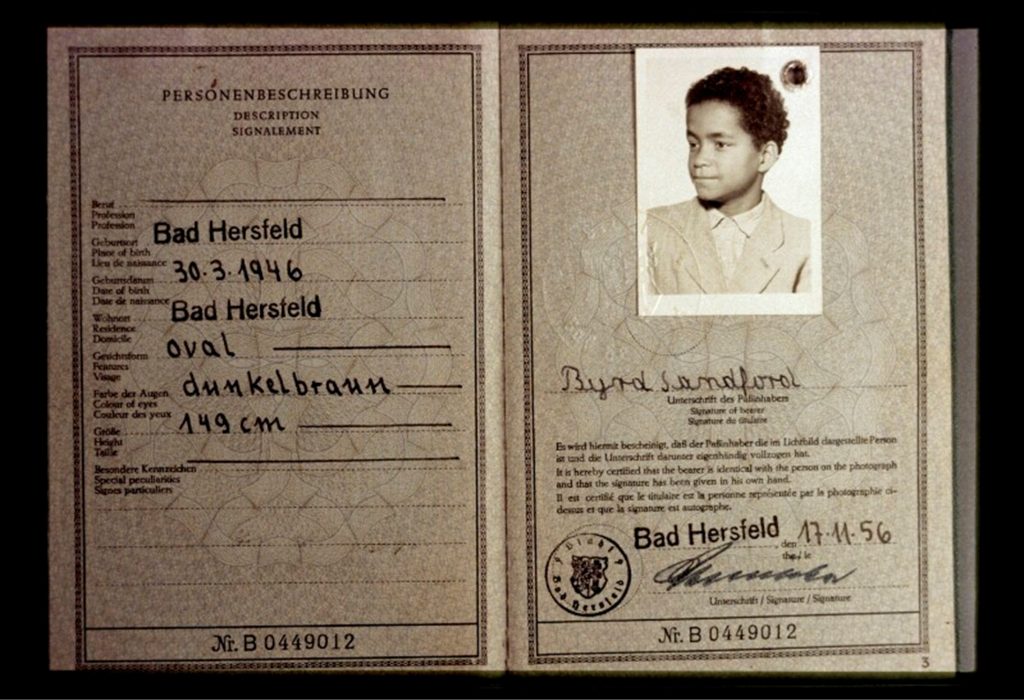

Sanford Byrd’s earliest memories are within an orphanage in Essen and Bad-Herzfeld, Germany. He did not know his biological parents and he also mentions that Sanford is not his actual name. He also is unsure whether the date listed on his birth certificate is correct or not.

Part 1, 8:58 “But my name in Germany was Franz. That’s F-R-A-N-Z, which I think the English interpretation is Frank. Franz Xavier, which is a Saint’s name since I was Catholic. Well, they told me I was Catholic. I was too young to have any religious beliefs. Xavier and Maria, which really in Germany wasn’t unusual for a boy to have a girl’s name, especially if was a saint, a patron saint. And then Riemschneider. Okay. Riemschneider is spelled R-I-E-M-S-C-H-N-E-I-N-D-E-R. Riemschneider, which literally translated means belt tailor. Riem being a belt, and Schneider is a tailor”

Throughout the oral history Sanford recalls his time within the orphanage and how being black in Germany was much different than being black within the United States. Broken into three parts, listeners are able to travel with Sanford across the states, learn and listen to the German language, and listen to the light banter between father and son as he recalls his personal history.

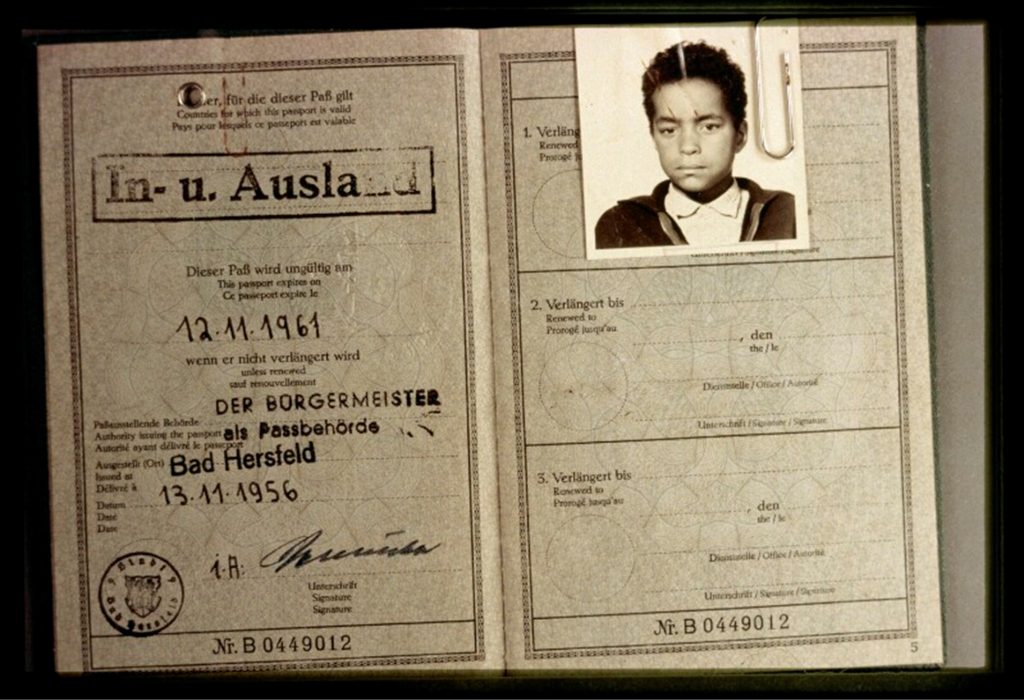

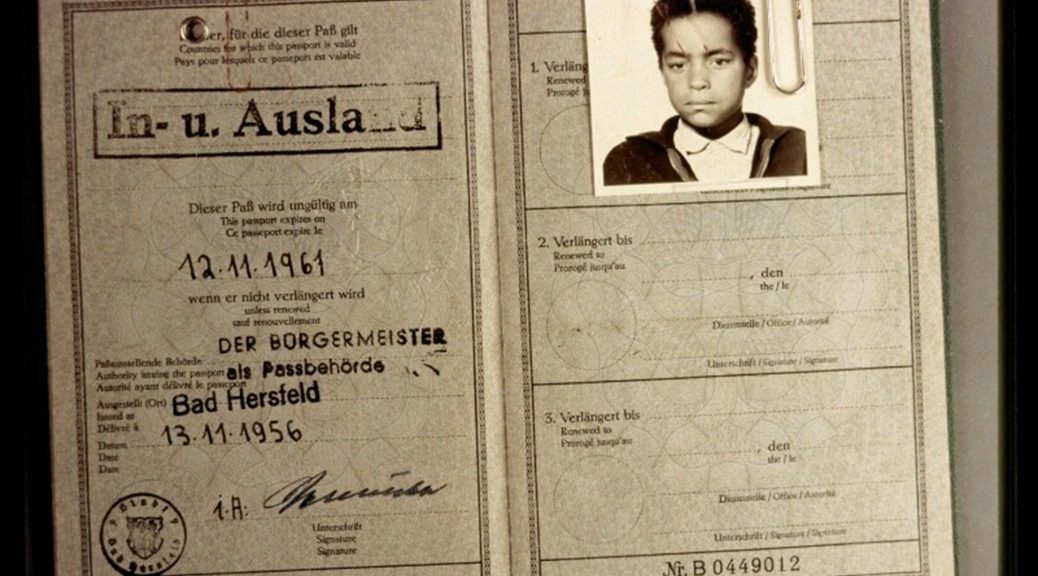

By searching for Sanford’s interview in the search bar at the top of the page, researchers and listeners are also able to come across Sanford’s German adoption files and pictures of young Sanford from his passport.

Thanks for sharing this insightful series! The depth of exploration into the “Behind the Veil” collection is truly fascinating.