This post originally appeared on H-Net on June 29, 2016. Post contributed by Laura Wagner, Ph.D., Radio Haiti Project Archivist.

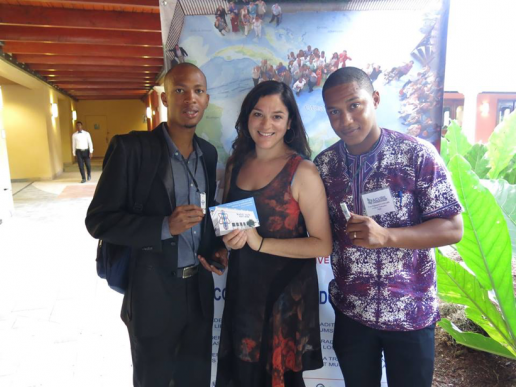

In June 2016, with the processing of the Radio Haiti archive well underway but only partially completed, we took another big step in bringing Radio Haiti home. I traveled to Haiti to present the archive project at the Caribbean Studies Association (CSA) and Association of Caribbean University, Research, and Institutional Libraries (ACURIL) conferences, both of which were held in Port-au-Prince during the same week, and brought with me a thousand flash drives. Each flash drive contains a small sample of twenty-nine Radio Haiti programs, and is emblazoned with Radio Haiti’s iconic microphone-inspired vèvè logo and the permanent URL of the collection’s finding aid.

The contents of the flash drives span nearly thirty years, from 1973 to 2002. It includes subjects ranging from the Battle of Vertières and the Haitian Revolution, the annual vodou pilgrimage to Saut d’Eau, the brutality of the Duvalier regime, the tribulations of Haitian refugees at sea, the 1987 Jean Rabel massacre, the persecution of Haitian cane-cutters in the Dominican Republic, the aftermath of the coup years, agrarian reform in the mid-1990s, women’s rights, and the search for justice in the assassination of Jean Dominique and tributes to the slain journalist. It includes the voices of journalists, writers, human rights activists, rural farmers, artists, and intellectuals. Jean Dominique, Michèle Montas, Richard Brisson, Madeleine Paillère, J.J. Dominique, Konpè Filo, Jean-Marie Vincent, Michel-Rolph Trouillot, and Myriam Merlet, among others. Each flash drive also contains a PDF containing a full list of the contents, and links to our permanent finding aid, Soundcloud site, Facebook page, and the trilingual pilot website.

Collaborators, friends, and fellow travelers, including the Fondasyon Konesans ak Libète (FOKAL), the MIT-Haiti Initiative, AlterPresse, and Fanm Deside (among others!) are helping distribute the flash drives throughout the country. Our goal is for copies to be available in various schools, universities, community radio and alternative media outlets, community libraries, grassroots organizations, cultural organizations, and women’s organizations from Cité Soleil to Jérémie to Cap Haïtien to Jacmel to Gonaïves to La Gonâve. In 2017, when the Radio Haiti archive is completely digitized and processed, we will give digital copies of the entire archive to the Archives Nationales, the Bibliothèque Nationale, the network of community radio stations SAKS, FOKAL, and other major institutions.

Radio Haiti’s digital archive is not only for scholars writing about Haiti; it isn’t even principally for them. It is for everyone. Radio in Haiti in general, and Radio Haiti in particular, was and is fundamentally democratic. The technology is relatively inexpensive. Even if you don’t have a radio yourself, a relative, a friend, or a neighbor does. Radio doesn’t depend on traditional literacy. And Radio Haiti itself was in Haitian Creole in addition to French, so that everyone could listen, participate, and share ideas. Radio Haiti demonstrated that Creole, the language spoken by all Haitian people, could be used for serious topics and serious analysis.

Radio in Haiti began with Radio HHK, a propaganda tool of the 1915-1934 US Marine occupation. In the 1970s, churches distributed small transistor radios. These radios were locked, to prevent people from listening to things other than church stations. But the listeners managed to unlock them in order to listen to other frequencies, especially Radio Haiti Inter on 1330 am. There is a long history of resourcefulness and innovation in Haiti—a history of degaje.

The Internet still is not as democratic as radio. It is not free. Not everyone has Internet access, and not everyone can buy enough data to livestream the digital archive. Despite that, I remain certain that the Radio Haiti archive will spread. Just as people took a propaganda tool and used it for their own purposes, they’ll find a way. Just as people unlocked the church radios, they’ll find a way. We want and encourage that. We hope that people will copy the content of these flash drives and share it with others, and that those who are able to download the audio will copy it, put it on a flash drive, share it with others.

* * * * * * * * * * * * *

The weekend after the conferences, I left Port-au-Prince to travel to the Artibonite to visit Charles Suffrard, one of Jean Dominique’s closest friends and collaborators, a leader of KOZEPEP, an influential peasant rights organizations in Haiti. In a posthumous tribute to Dominique, which is one of the recordings featured on the flash drives, he introduces himself as “a rice farmer, and Jean Dominique’s teacher,” referring to the journalist’s uncommon respect for the expertise and experience of Haiti’s cultivators. We eat lalo and local rice from Charles’s fields. Then he takes me to the dam where they poured Jean Dominique’s ashes, after he was struck down by an assassin in Radio Haiti’s courtyard early in the morning of April 3, 2000. “This is the most important thing for you to see,” Charles says.

It feels like a pilgrimage: if I am to work on this archive, I must also know this place. The water was high and quick-moving, cloudy with sediment. “This is where all the water that irrigates the whole Artibonite Valley comes from,” Charles explained. “This is why we chose to pour Jean’s ashes here, so that he could become fertilizer for the entire Artibonite.”