My current book project, Southern Sapphisms: Sexuality and Sociality in Literary Productions 1969-1997, considers how queer and feminist theories illuminate and complicate the intersections between canonical and obscure, queer and normative, and regional and national narratives in southern literary representations produced during a crucial but understudied period in the historical politicization of sexuality. The advent of New Southern Studies has focused almost exclusively on midcentury texts from the Southern Renascence, largely neglecting post-1970 queer literatures. At the same time, most scholarship in women’s and feminist studies continue to ignore the South, or worse, demonize the South as backward, parochial, and deeply homophobic. Southern Sapphisms argues that we cannot understand expressions of lesbianism and feminism in post-Stonewall era American literature without also understanding the explicitly southern dynamics of those writings—foregrounding the centrality of sexuality to the study of southern literature as well as the region’s defining role in the historiography of lesbian literature in the United States.

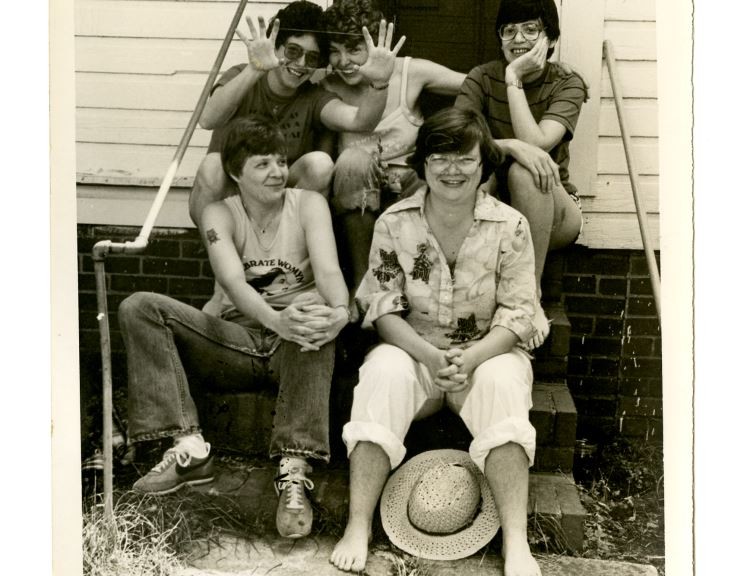

Vital archival work completed at the Sallie Bingham Center this past May strengthened my arguments about the formations of lesbian identity and community in the North Carolina lesbian-feminist journal Feminary (1969-1982). Feminary has been lauded by one scholar as “the source and backbone of contemporary Southern lesbian feminist theory,” due in part to the forum it provided for southern lesbians to voice their inimitable outlooks on race, regionality, and social justice[i]. At a local level, Feminary forged and grounded a community of Durham/Triangle feminists, lesbians, and women writing and printing as a collective. At a national level, I show how the women of this journal were actually inspired by the increasingly turbulent battles over civil rights in the South. This revelation upends prevailing notions that the Stonewall riots in New York were the watershed that changed lesbian and gay politics and culture in the nation. My work on Feminary recasts dominant national narratives about queer lives, histories, and activism in the region by illustrating how lesbian feminist politics gained their inspiration and momentum not only from Stonewall, but also from the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr., and massive resistance against civil rights and gay and lesbian rights in the South. Access to rare archival documents—only available at Duke University’s Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library—prove that Second Wave feminism and modern lesbian politics have extensive southern roots. To ignore the distinctly regional dynamics of those roots is to misunderstand the complexity of those movements across the nation and beyond.

I am grateful for the support of the Mary Lily Research Grant, which enabled my research at the Sallie Bingham Center for Women’s History and Culture. I was able to consult materials from the Minnie Bruce Pratt Papers and the Dorothy Allison Papers, and was honored and humbled to use the Mab Segrest Papers.

I was fortunate to consult early drafts of works that would later develop into an impressive body of southern lesbian literature. Many literary productions made their first appearances in Feminary, namely volumes of poetry including Dorothy Allison’s The Women Who Hate Me (1983), Minnie Bruce Pratt’s The Sound of One Fork (1981), and Mab Segrest’s Living in a House I Do Not Own (1982); Pratt’s and Segrest’s essay collections, Rebellion (1991) and My Mama’s Dead Squirrel; Cris South’s novel, Clenched Fists, Burning Crosses (1984); and Allison’s first work of fiction titled Trash (1989). Beyond these advancements, Feminary functioned as more than a print culture space for literary circulation and consumption—it flourished as a galvanizing force through which southern lesbians might engage in coalition politics at a crucial time in the 1970s and 1980s, or, as Pratt recalls, “we talked about race and racism, so-called race, racism. We had really interesting conversations about the intersections, what later got called the intersections. But that’s what we were doing. We weren’t just being lesbians.” (Minnie Bruce Pratt interview, Voices of Feminism Oral History Project, Sophia Smith Collection).

In an effort to add texture and depth to this research narrative, I want to share some of my personal notes scribbled down while in the reading room (see below). Here I seek to articulate my own experience of doing research at the Sallie Bingham Center — how it felt to do queer archival research at that very moment in the archive. Engaging in archival research offers a profoundly queer temporal experience — and temporary existence. Research within the archive necessitates a dissociative shift in being and thought: scholars become lost in the present, enveloped into the past. This is why we often feel a disturbing vertigo upon exiting the archive — a separation in our being and thinking with the past. Part of this vertigo is the experience of handling material artifacts that carry with them an aggregate, temporal stickiness that accrues through each reading and interpretation: then, now, and all the intervening, cataloguing years. I am grateful for these affective memories — a surprise here and there, upon finding something you didn’t know existed, the sound of discovery piercing the hallowed silence of the reading room — small pleasures I carry with me long after my research is done:

Mab Segrest Papers

Box 3_Writings_2

Folder entitled “Mab’s Book, 1982” : this are materials from LIVING IN A HOUSE I DO NOT OWN. Ditto papered poems, arrangements of poem form on page, scraps of paper with thematic resonances.

SEE SCANS. Film negatives of cover; four. Gorgeous and haunting.

Minnie Bruce Pratt Papers

Box 30

Feminary IX.2, Summer 1978, cover image of full roses. About to break for lunch. Can’t help but notice that Duke has tons of honeysuckle. Both seem apt images for the journal.

[i] Tamara M. Powell, “Look What Happened Here: North Carolina’s Feminary Collective,” North Carolina Literary Review 9.1 (2000): 92.

Post contributed by Dr. Jaime Cantrell, Visiting Assistant Professor of English,The Sarah Isom Center for Women’s and Gender Studies faculty affiliate, The University of Mississippi