This post is by Heidi Madden, Librarian for Western European and Medieval/Renaissance Studies, and Sarah How, European Studies Librarian at Cornell University.

International book fairs provide great opportunities for librarians to discover new books and other media; learn of new trends in publishing, translation, design, and book production; and build personal connections that directly benefit both their own work and that of their home institutions. Being abroad, being there in person, immersed in the language and culture of another place, is in itself of significant benefit, although one that is difficult to quantify. That is why we are grateful for the opportunity afforded by this library blog to write about our experiences at the 2019 Frankfurt Book Fair, and thereby to describe some of those benefits.

For international and area studies librarians, book fair visits are an essential component not only of professional development but also of collection development. That serious research libraries need materials that would not — could not, economically — be provided by our standard commercial supply channels is accepted wisdom in the profession. Book fair visits are an efficient way to address this need, since they make it possible to interact with many publishers at once, in a single exhibition space. In addition, cultural and linguistic immersion at international fairs strengthens the skills and knowledge that support research services and give academic librarians “street cred” with international students and faculty, as well as researchers engaged in foreign-language humanities, social sciences, and area studies. Visits to specialized bookstores, meetings with local librarians, and visits to local libraries and cultural institutions can be squeezed-in around a busy fair schedule for additional benefit. This is especially true for those librarians who are able to attend an international book fair in a place as rich in resources as Frankfurt, Germany.

The logo of the 2019 Frankfurt Book Fair.

The Frankfurt Book Fair (Frankfurter Buchmesse), an annual international event for the publishing trade community, is the world’s largest book fair. This Fair is fundamentally a commercial event, focused as it is on the business of publishing and related industries. It is the place, for example, where publishers, agents, authors, illustrators, film makers, translators, printers, authors, media specialists, book distributors, and libraries negotiate and license rights for distribution, publishing, translation, and film and media versions of the items on display. However, the Frankfurt Book Fair is also the occasion for substantial programming related to contemporary literature and, as we shall see, can even serve as a forum for robust cultural and political debates. Similarly-designed book fairs, more regional in scope, are held in Paris (Salon du livre), Bologna (Bologna Children’s Book Fair), Madrid (Liber), Guadalajara (International Book Fair), Beijing (International Book Fair), Hong Kong (Book Fair), and Moscow (International Book Fair), to name just a few.

According to established tradition, the Frankfurt Book Fair lasts for 5 days, from Wednesday to Sunday. The first three days are usually focused on exhibiting books. On those days, a European Studies librarian can, for example, peruse the publishing program of dozens and dozens of publishers from every European country, including small, independent presses. On the weekend, the fair is open to the public, and books are sold directly to individuals. On those days the sections of the fair devoted to publishers of graphic novels, cookbooks, travel literature, zines, and German language fiction are jammed with people and cosplay participants. In October 2019, 302,267 individuals from 100 countries visited the Frankfurt Book Fair. There, they were met by 7,500 exhibitors and encountered 400,000 individual books, maps, manuscripts, visual materials, and digital media objects (audio and e-books).

The special exhibit of the guest country Norway combined nature imagery, mirrors, and book tables designed to represent poems in spatial dimensions. Norway also celebrated 500 years of the printed book (Nidaros Missal and the Nidaros Breviary, from 1519) in the exhibit.

Each year, Frankfurt hosts a “Guest of Honor” country: Norway was the 2019 Guest. The guiding theme for the Norwegian events and exhibits was “The Dream We Carry.” The theme title was inspired by the famous Norwegian poet Olav H. Hauge, and his poem “It is that Dream.” Norway sponsored prominent Norwegian writers, who spoke and schmoozed with the attendees, while fair organizers produced a free bibliography of new publications from Norway in German translation to promote writers and publishers to the German reading public. Karl Ove Knausgård, a Norwegian author who has been described as one of the 21st century’s greatest literary sensations, spoke in several different settings, both about his own work and about his recent experience curating an exhibit on Norwegian painter Edvard Munch, whose best known work, The Scream, has become one of the most iconic images of world art. In other interviews, contemporary Norwegian authors Erik Fosnes Hansen and Erika Fatland covered a diversity of topics, from the Oslo cultural scene to food science, which is at the heart of Hansen’s novel Et Hummerliv (“A Lobster’s Life”). Maja Lunde spoke about her forthcoming book The End of the Ocean, while Jo Nesbø was interviewed about Knife, the next installment in his Harry Hole series of crime novels. More highlights and full listing of authors can be found in the online program.

Karl Ove Knausgård amd Jurgen Boos (CEO of the Frankfurt Book Fair)

Norwegian literature was represented by many authors reading from their work.

In addition to lectures and authors’ talks, the Frankfurt Book Fair also hosts special celebrations for the winners of the Nobel Prize, the German Book Prize, and the Peace Prize of the German Book Trade. Overall, ninety-three prizes were awarded by various organizations during the book fair in 2019. Polish-born 2018 Nobel Laureate Olga Tokarczuk (awarded in 2019) spoke at the opening session of the Fair. Oddly, Austrian-born Peter Handke, the 2019 Nobel Laureate, was not present in person, and was only represented by his publisher’s special display. Handke’s absence did not prevent him from becoming the subject of intense controversy. Saša Stanišić, the winner of the 2019 German Book Prize, who fled to Germany with his Bosnian mother and Serbian father in 1992, was the most prominent voice at the book fair, taking Handke to task for his sympathetic attitude toward former Serbian president Slobodan Milošević, the first sitting head of state to be charged with war crimes.

World newspapers, including The Guardian, chronicled the Handke debate. One of its articles, entitled “A troubling choice: authors criticise Peter Handke’s controversial Nobel win. reported on the views of famous international writers, such as Salman Rushdie, Hari Kunzru and Slavoj Žižek who opined that the 2019 Nobel laureate “‘combines great insight with shocking ethical blindness’.” Another article, entitled “Peter Handke’s Nobel prize dishonours the victims of genocide,” referenced the Austrian writer’s stance on the Yugoslav Wars in the 1990s, which has been characterized by some critics as genocide apologism. At some point during October 2019, Peter Handke announced that he would no longer speak to journalists, so for now the debate will continue in literary circles, and will most likely re-emerge around the December 10, 2019 Nobel Prize Award Ceremony.

The 2019 Peace Prize of the German Book Trade was awarded to Sebastião Salgado, the first ever photographer to receive this prize. During the course of several interviews, the Brazilian social documentary photographer and photojournalist introduced his book Gold, which showcases haunting images of Amazonia taken in the 1980s. As with his other work, Gold highlights environmental and human rights issues by investigating habitats and communities with his camera.

Cultural events inspired by Norway as the Guest of Honor were only a fraction of the international author events and talks at the Fair and in the city of Frankfurt. The gala of literary stars included Margaret Atwood, Maja Lunde, Elif Shafak, Colson Whitehead, Ken Follett, and Jo Nesbø (video Highlights can be seen on the Fair’s website). More media outlets broadcast from the book fair than can be mentioned here. The two outlets with the most video content are ARD Mediathek and ZDF Mediathek, especially the venue “Das Blaue Sofa,” which gives access to 90 interviews with authors from the Frankfurt 2019 fair alone. Social media followed along under #fmb19, and have already transitioned to the hashtag for the 2020 fair, #fbm20, as planning for the next fair gets underway. Canada will be the Guest of Honor at the 2020 Frankfurt Book Fair.

On Saturday and Sunday, while the public floods into the fairgrounds, specialized, ticketed, professional events are held at the Frankfurt Book Fair. The two that we attended this year were the 7th International Convention of University Presses 2019, which focused on the European Accessibility Act, and an event for non-fiction editors. The non-fiction publishing event “Non-fiction Publishing: It’s a Women’s World,” consisted of a panel and discussion with female publishers from Morocco, Turkey, India, and Norway, who spoke about their experiences with producing important works documenting and giving voice to issues and experiences which might not find a home with large commercial publishers.

Look for more on Frankfurt hot topics in the next blog post on Welcome to the VUCA World! The Frankfurt International Book Fair 2019. Part 2

Frankfurt Book Fair 2019 publisher displays

Frankfurt Book Fair 2019 publisher displays

On Saturday, cosplay fans come dressed as their favorite characters.

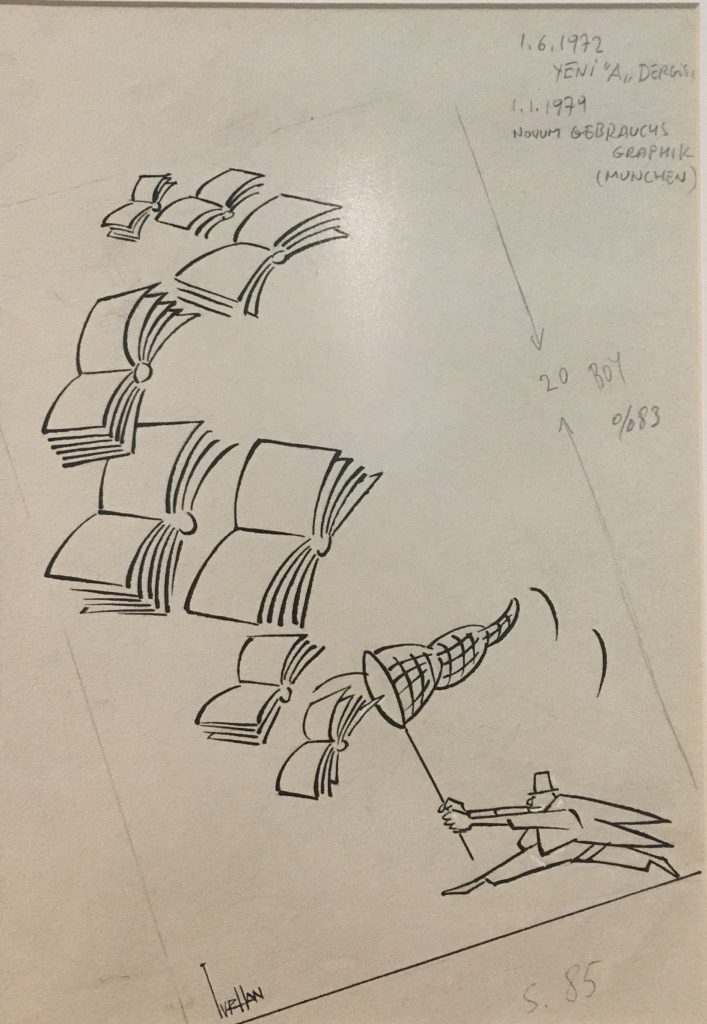

“Stellt das Buch her / Make the book”: three containers stacked on top of each other, with exhibits on each level in the courtyard of the book fair.