This blog post by Sean Swanick, Librarian for Middle East, North Africa, and Islamic Studies, Duke University is part IV of a short series exploring Duke University Libraries’ holdings about the 1923 Treaty of Lausanne and the Population Exchange between Greece and Turkey. Access Part I here, Part II here, and Part III here.

Anatolia (Ottoman Turkish آناطولی, Anadolu), is etymologically derived from the Greek Ἀνατολή (Anatole) but in Greece to this day is commonly referred to as Μικρὰ Ἀσία (Mikra Asia) or Asia Minor. It is a peninsula in present-day central Türkiye. Located between 1,000 and 1,500 metres above sea level, this vast terrain of arable and steppe land is bounded by three seas (Mediterranean to the south, Black to the north, and Aegean to the west) and dotted by spectacular rock formations known as “Fairy chimneys.” These are particularly prevalent in Cappadocia, Central Anatolia. The region is known for its soft volcanic rock, which was relatively easy to carve, because of this as well as a means of protection carved homes, churches, and monasteries into the rock.

Unfortunately, Anatolia was not spared the instability and violence that followed the 1919-1922 Greek-Turkish War. Scholars note that approximately one in every four people in Greece were exchanged in 1923 while in Turkey it is suggested that one in three people were similarly affected by the wars preceding the Population Exchange and the Exchange itself in 1923. In the regions along the Aegean and Black Sea coasts, the Greek Orthodox communities left shortly before the Population Exchange of 1923, in large part to escape the Greek-Turkish War. In Cappadocia, the Greek Orthodox communities were largely shielded from the fighting caused by the War. However, their fate would still be determined by this armed military conflict, as these communities were the largest number of people in Türkiye to be exchanged in 1923.

The Karamanlides of Central Anatolia

Among the many ethnic and religious communities that lived on Anatolia prior to the Population Exchange of 1923 was a group of Turkish-speaking Greek Orthodox Christians known as the Karamanlides (Gk: Καραμανλήδες), because they wrote in Turkish using the Greek alphabet (Karamanlı Türkçesi; Gk: Καραμανλήδικα, Karamanlidika). Largely because Turkish was their native tongue, the Church and Greek Orthodox Christianity of the Karamanlides was their unifying identity. This differentiated them from their neighbours, both Christian (Armenian Orthodox and Catholic) and Muslim (Turkish).

In 1923, most of the Karamanlides population, approximately 100,000 people were exchanged and relocated to various places in Greece. The communities lived throughout this region in towns and centres such as Prokopi (now Ürgüp), Kalvari (now Gelveri) and Sinasos (now Mustafapaşa). They were moved to various parts of Greece, especially the Kavalla region. In these newly formed centres, many of the refugees longed for home, the land they had lived on and cultivated for decades, if not centuries. As an act of remembering their departed home they renamed their new communities after those longed-for homelands, e.g., New Prokopi, New Kalvari, and New Smyrna.

Housing the Exchanged Populations

With the agreed-upon transfer of 1.6 million people, both Greece and Turkey set about to find housing for their new citizens. In Turkey, the majority of the population transfer occurred prior to 1923 with the Balkan Wars of 1912-1913 being the most significant—some 2 million people had arrived prior to 1923 many of whom were destitute and poor. However, the government went about building new settlements and revitalising old housing, not the least of which belonged to Greek Orthodox people who were exchanged to Greece. The exchange of 1.6 million people in a short amount of time was bound to cause major issues, no matter how efficient the bureaucracy.

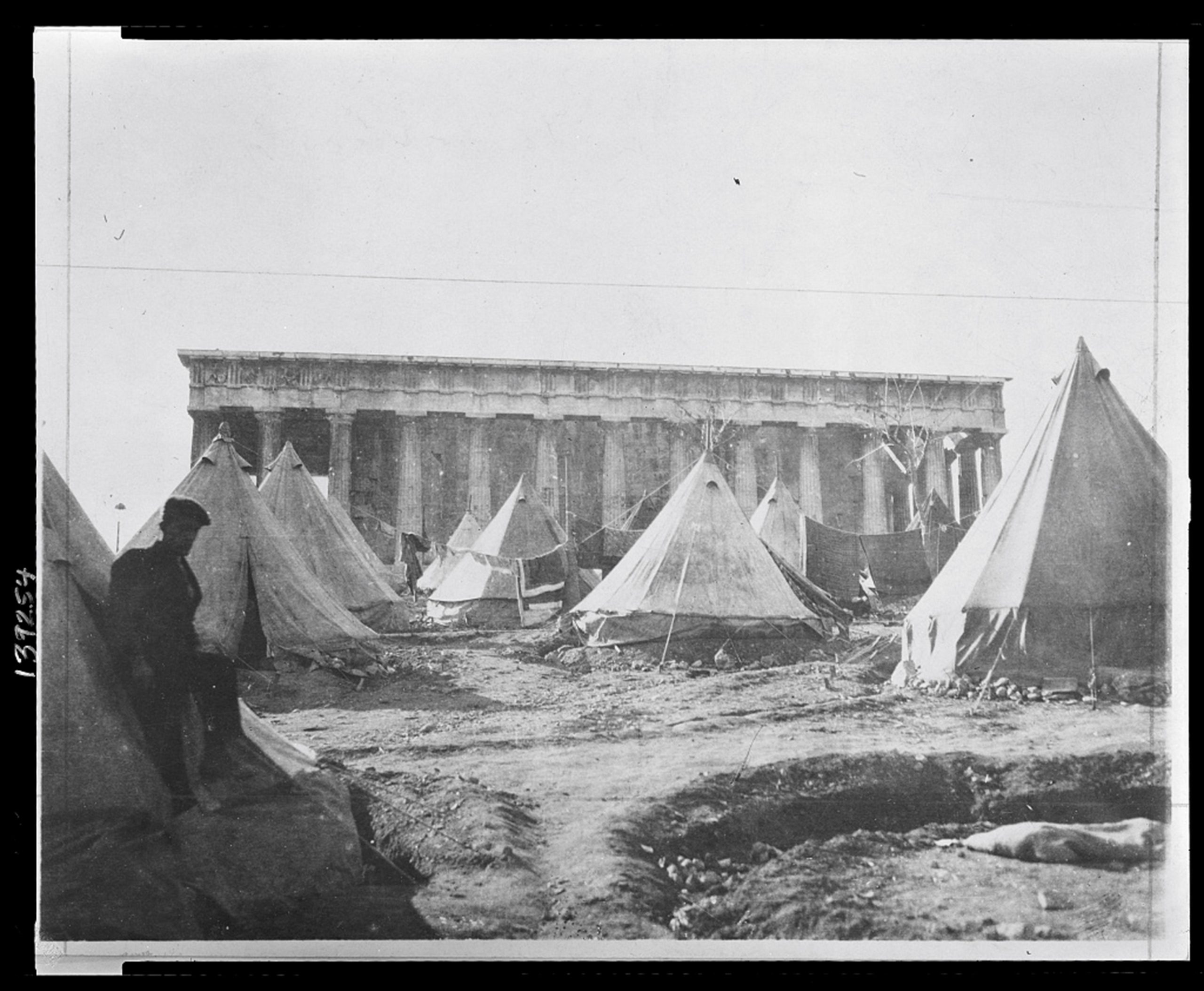

In Greece, the housing issues were even more pronounced, primarily because the nation-state received over 1 million people in a very short amount of time. Recalling that Greece had a population of approximately 5 million people in 1922, the influx of over 1 million people inevitably led to disaster. Government agencies received financial aid and other means of support from local and international organisations. However, this assistance was not enough to provide adequate housing and some refugees were forced to live in tents or make-shift housing while waiting for proper housing.

Further reading

Andaloro, Maria. 2009. La Cappadocia e il Lazio rupestre : terre di roccia e pittura = Kapadokya ve kayalik Lazio bölgesi : kayalarin ve resmin topraklari.

Balta, Evangelia; translated by Alexandra Doumas. 2009. Sinasos: images and narratives.

Balta, Evangelia (ed.). 2010. Ürgüp: Küçük Asya Araştırmaları Merkezi arşivinden fotoğraflar.

Balta, Evangelia. 2010. Beyond the language frontier: studies on the Karamanlis and the Karamanlidika printing.

Balta, Evangelia and Mehmet Ölmez (eds.). 2011. Between religion and language: Turkish-speaking Christians, Jews and Greek-speaking Muslims and Catholics in the Ottoman Empire.

Balta, Evangelia (ed.) with the contribution of Mehmet Ölmez. 2014. Cultural encounters in the Turkish-speaking communities of the late Ottoman Empire.

Cengizkan, Ali. 2004. Mübadele konut ve yerleşimleri : savaş yıkımının, iç göçün ve mübadelenin doğurduğu konut sorununun çözümünde “İktisâdı̂ hâne” programı, “Numûne köyler” ve “Emval-i metrûke”nin değerlendirilmesi için adımlar.

Eyduran, Necati (ed.). 2023. Mübadele insanları fotoğraf albümü.

Ousterhout, Robert G. 2017. Visualizing community: art, material culture, and settlement in Byzantine Cappadocia.

Soykan, Nazlı. A.2017. Aksaray-Belisırma Karagedik Kilise.

de Tapia, Aude Aylin. 2023. Orthodox Christians and Muslims in Cappadocia: Local Interactions in an Ottoman Countryside (1839-1923).

Tzonis, Alexander and Alcestis P. Rodi. 2013. Greece: modern architectures in history.

“Yunanistan’da Kapadokyalı mübadiller Anadolu kültürünü yaşatıyor.” Derya Gülnaz Özcan. Anadolu Ajansı.