Post contributed by Jonathan S. Jones, historian and PhD candidate at Binghamton University

In the Civil War’s wake, thousands of veterans became addicted to medicinal opiates. Hypodermic morphine injections and opium pills were standard remedies in the Civil War era for amputations, sickness, and depression, and they often lead to addiction. Take, for example, the case of A.W. Henley, a Confederate veteran, who recalled in 1878 that, “In the army, I had to use opiates for a complication of painful diseases.” The medicine soon “fastened its iron grip on my very vitals, and held me enchained and enslaved for near fifteen years.”[i]

Historians have long recognized the causative link between Civil War medical care and the high rate of opiate addiction among veterans. However, although we know that doctors were in many ways the originators of the postwar addiction epidemic, we know surprisingly little the about the medical response to the crisis. Did American doctors ignore the opiate addiction among veterans, or did physicians seek to help veterans suffering from addiction? And if so, what did those efforts look like?

These are questions I seek to answer in my dissertation, “A Mind Prostrate”: Opiate Addiction in the Civil War’s Aftermath.” My research benefited greatly from a History of Medicine Collections Travel Grant, awarded by the Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library. The History of Medicine Collections at the Rubenstein Library includes several manuscripts and rare items that suggest answers to elusive questions about the medical responses to Civil War veterans’ opiate addiction.

THE BLAME GAME

Physicians fell under a wave of criticism after the Civil War for causing opiate addiction crisis. Veterans and observers in the media accused doctors of overprescribing opiates to ailing old soldiers and other patients, resulting in widespread opiate addiction. This criticism posed a problem for physicians—so-called “regular” doctors—because it undermined their precarious position in the hyper-competitive Gilded Age medical marketplace. Physicians had been struggling to out-compete alternative healing sects and “quacks” for decades. Being labeled the culprits for the crisis only weakened the regulars’ footing in this struggle.

CHANGING PRESCRIBING PATTERNS

In response to this professional crisis, some physicians advocated for a move away from prescribing medicinal opiates. During the 1870s and 1880s, ex-military surgeons, in particular, exhorted their colleagues in medical journals and scientific studies to prescribe fewer opiates, to substitute the drugs with supposedly less-addictive painkillers, and even to refrain from prescribing opiates altogether. As the ex-Union surgeon Joseph Woodward surmised in 1879, “The more I learn of the behavior of such cases [of overprescribing] under treatment, the more I am inclined to advice that opiates should be as far as possible avoided.”[ii] Such proposals were truly radical, considering that opiates were the most commonly prescribed medicines of the nineteenth century up to that point.

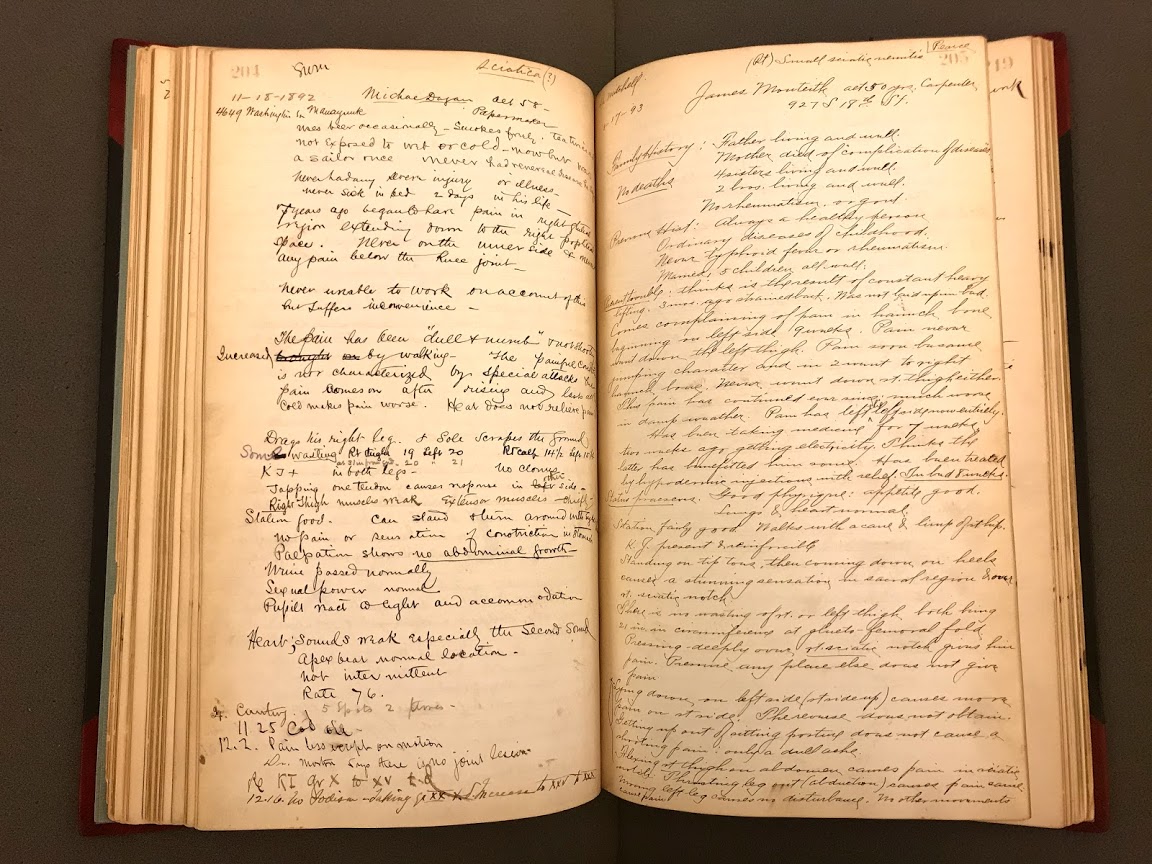

But did physicians heed these warnings? Were radical proposals merely hypothetical, or did physicians implement them in practice? To answer these questions necessitates the close analysis of late nineteenth century clinical records. I was fortunate enough to stumble across one such record in the History of Medicine Collections at the Rubenstein Library, a rare casebook from the Philadelphia Orthopaedic Hospital and Infirmary for Nervous Diseases, professional home of the physician Silas Weir Mitchell.

An eminent neurologist, Mitchell was one of the most vocal members of the anti-opiate camp. Mitchell—whose infamous “rest cure” inspired the feminist Charlotte Perkins Gilman to write The Yellow Wallpaper, a feminist critique of Mitchell’s methods—was a prolific writer. In many of his medical works, he railed against the habit-forming potential of medicinal opiates and doctors’ role in facilitating opiate addiction. As Mitchell explained in an 1883 work about pain management, “often, in my experience, the opium habit is learned during an illness of limited duration, and for the consequences of which there is always some one to be blamed.” He blamed doctors who were “weak, or too tender, or too prone to escape trouble by the easy help of some pain-lulling agent” for causing their patients to develop opiate addiction.[iii] Doctors must refrain from prescribing opiates empathetically, Mitchell warned, lest the medical profession continue to be blamed for the opiate addiction crisis.

Accordingly, Mitchell’s clinical records confirm that he stopped prescribing opiates to chronic pain patients, those at greatest risk for addiction, in his own clinic. Mitchell’s clinic, the Philadelphia Orthopaedic Hospital, was the cutting edge of American neurology in the late nineteenth century. Doctors working there alongside Mitchell specialized in treating chronic nervous pains, headaches, and other symptoms classified under the diagnostic category of neuralgia. During the previous decades, most of these individuals would have been treated with opiates. Indeed, Mitchell prescribed opiates heavily during the Civil War, witnessing the genesis of opiate addiction in several of his patients. Yet by the 1880s, Mitchell reversed course. The clinic’s casebook reveals Mitchell did not prescribe opiates to a single patient among the 62 individuals for which he recorded clinical notes between 1887 and 1900. Other physicians, I suspect, mirrored Mitchell’s increasingly conservative approach to prescribing opiates during the Gilded Age.

THE COMPETITION

But physicians like Mitchell were not alone in responding to the Gilded Age opiate epidemic. Ailing Americans could choose from a vast spectrum of treatments and healers to remedy their medical woes during late nineteenth century. Unlike today, regular physicians were often outcompeted by alternative healers during the Gilded Age. So-called “quacks”—at least, that is what physicians dubbed them—often impinged on physicians’ customer bases.

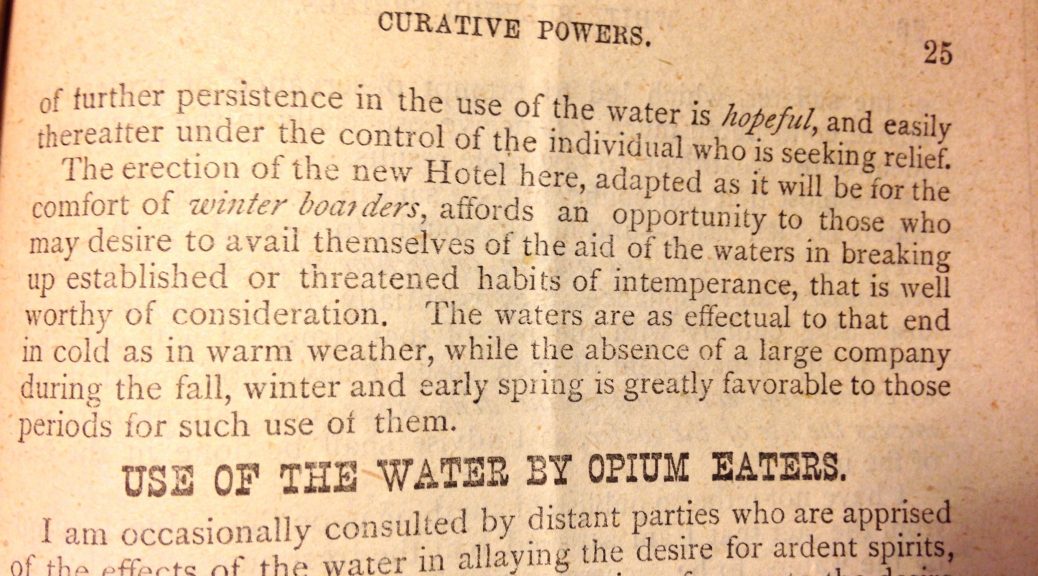

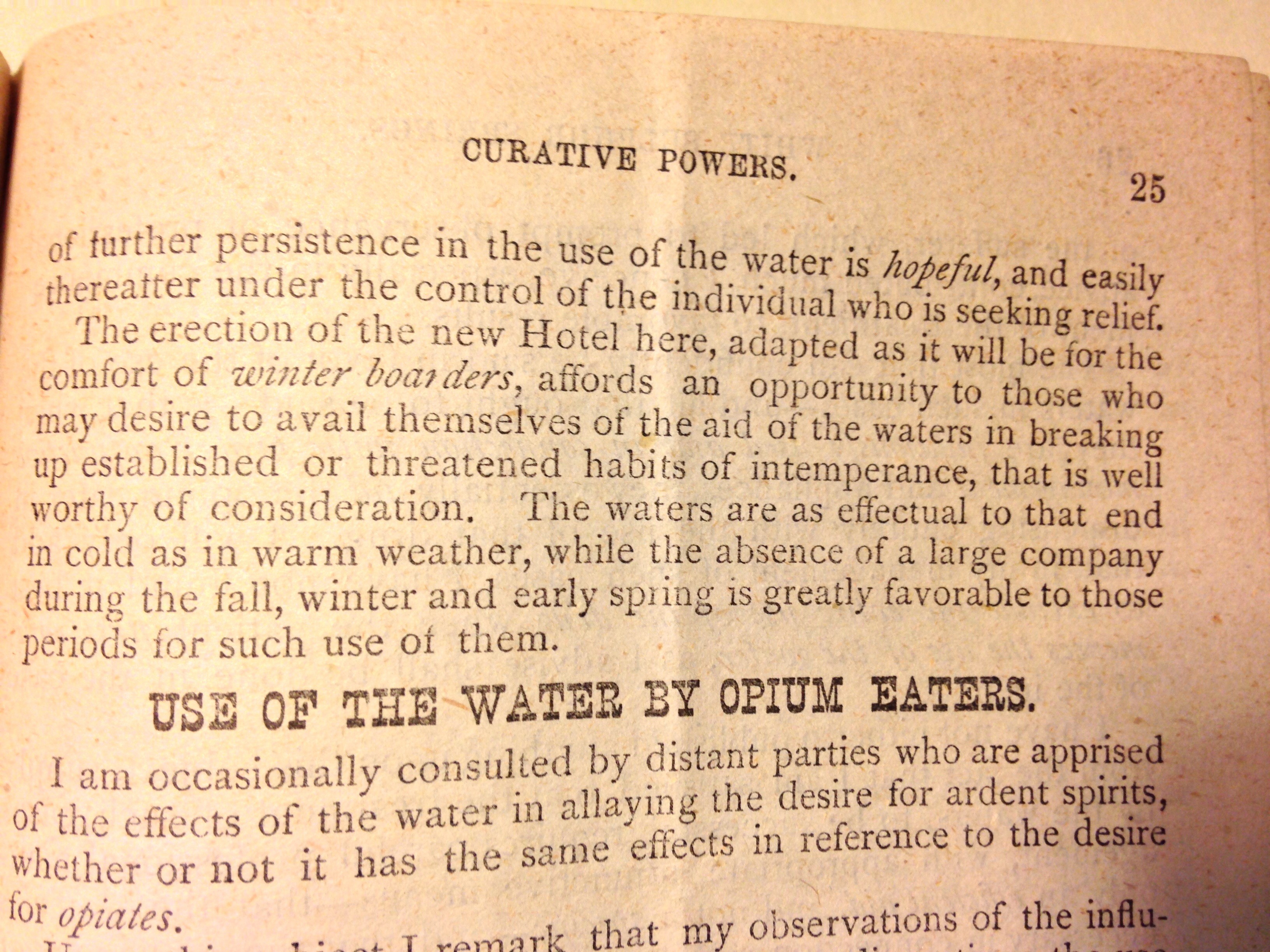

Dozens of entrepreneurial healers spotted new commercial opportunities amidst the rising rates of opiate addiction. They invented and marketed a diverse array of treatments for opiate addiction between the late 1860s and the turn of the twentieth century. John Jennings Moorman, the proprietor of a nineteenth century West Virginia hot springs resort, exemplified this trend. I encountered a rare copy of Moorman’s 1880 advertising pamphlet for his White Sulphur Springs resort in the Rubenstein Library. Founded in the late 1830s, Moorman marketed his exceedingly popular hot springs as a cure for a diverse spectrum of diseases during the antebellum years, from rheumatism to neuralgia, jaundice, scurvy, and others.

Always looking to expand his enterprise, Moorman perceived an opportunity in the rising rates of opiate addiction after the Civil War. Naturally, he expanded his operation to cater to opiate addicted customers desperate for a cure. Moorman began marketing White Sulphur Springs as a treatment for “opium eating” in 1880. Prior versions of Moorman’s marketing material do not include references to opiate addiction.[iv]

As Silas Weir Mitchell’s casebook and John Jennings Moorman’s advertising pamphlet indicate, Gilded Age medical practitioners responded to the opiate addiction crisis in diverse ways, from prescribing fewer opiates to marketing hot springs therapy for addiction. The rare medical manuscripts held by the History of Medicine Collections at the Rubenstein Library thus made significant contributions to my research, unlocking answers to elusive questions about the various medical responses to Civil War veterans’ opiate addiction.

—————————————————————

[i] Basil M. Woolley, The Opium Habit and its Cure (Atlanta: Atlanta Constitution Printer, 1879), 30.

[ii] Joseph Woodward, The Medical and Surgical History of the War of the Rebellion, Pt. II, vol. I (Washington D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1879), 750.)

[iii] S. Weir Mitchell, Doctor and Patient (Philadelphia: Lippincott Company, 1888), 93.

[iv] J.J. Moorman, White Sulphur Springs, with the analysis of its waters, the diseases to which they are applicable, and some account of society and its amusements at the Springs (Baltimore: The Sun Book and Job Printing Office, 1880), 25-26.