Any day now, the ticker at the top of the Rubenstein’s finding aids page will turn over and mark a milestone 2000th online finding aid. Doesn’t sound like much, especially when you consider that the Rubenstein Library holds more than 6,000 manuscript collections. But those 2,000 finding aids – narrative maps that guide a researcher through the contents of a manuscript collection’s boxes and folders – also represent thousands of hours of interpretive labor supplied by library staff. The first of these online collection guides debuted around 1996. They are encoded with an XML-derivative called EAD, and are now discoverable to a worldwide audience through any online keyword search. But finding aids – or inventories – or collection guides – go back a lot further than their online counterparts.

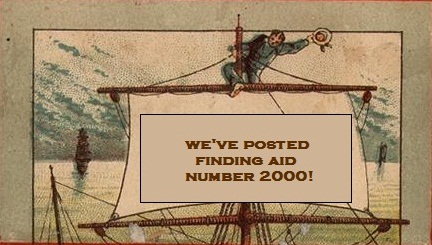

The winner of the 2,000th finding aid spot belongs to the Purviance Family Papers. Acquired as either a purchase or a gift by the Duke University Manuscripts Department in 1943 from an S. S. Barnes in Baltimore, the collection offers over 2300 manuscripts and 10 photographs, 4 maps, and 21 volumes (including an anonymous Civil War diary) belonging to a prominent Revolutionary-era Baltimore family with a compelling history. Shortly after it was received, a Manuscript Department archivist researched the collection and typed up a set of catalog cards: the Purviance Papers “finding aid.”

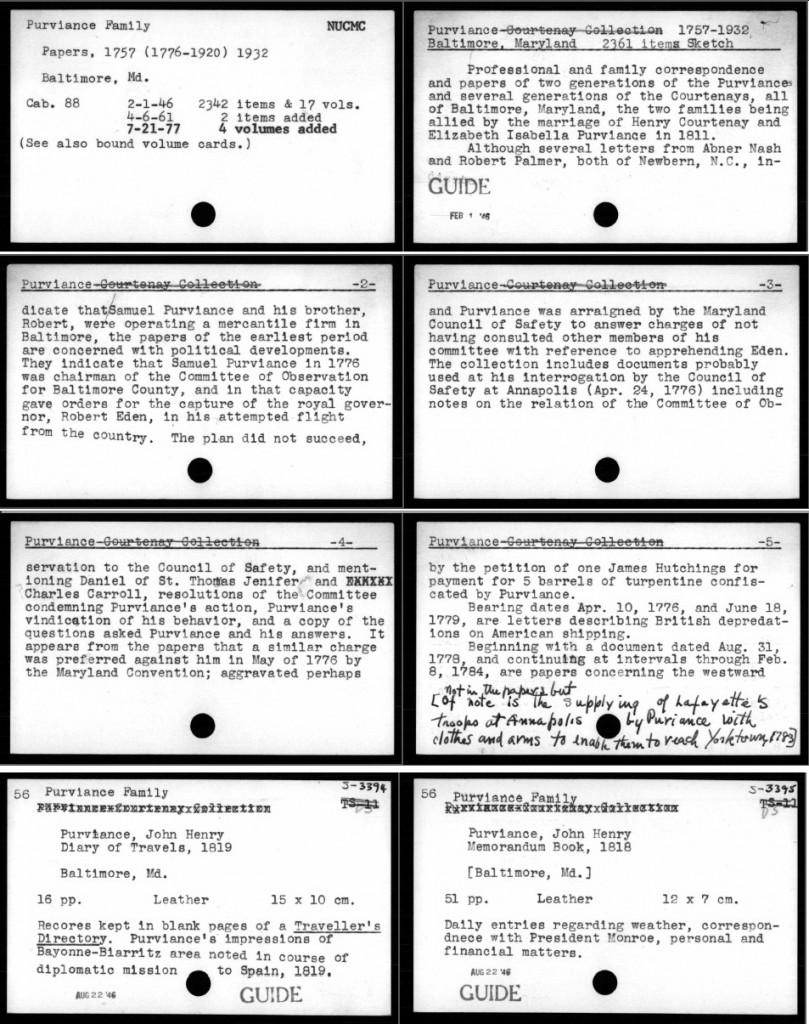

Defined most broadly, archivists consider a finding aid to be any document that assists in charting a path through the contents and topics of an archival collection – a big help when you’re dealing with a very large collection! In the 1940s at Duke, this was the role of the card catalog. Of course, you could only consult the cards if you traveled to the library, or if you could ask a reference archivist to help. Some collections were represented by three or four cards; some had close to a hundred. In 2012 – to the shock of older librarians who never thought they’d see the day – the entire card catalog was digitized and is currently being used as a resource for the reference archivists. Here is a sample of the 92 Purviance cards:  Collections were typically a lot smaller back then. As collections grew larger, a new generation of archivists started using more productive strategies for describing thousands of folders of manuscript items, and as part of this effort, they turned to creating more-portable paper inventories (but still on typewriters). Here’s an example of one, with a post-it note that marks a turning point in library history:

Collections were typically a lot smaller back then. As collections grew larger, a new generation of archivists started using more productive strategies for describing thousands of folders of manuscript items, and as part of this effort, they turned to creating more-portable paper inventories (but still on typewriters). Here’s an example of one, with a post-it note that marks a turning point in library history:

Enter the computer and Microsoft Word. When I started working in the library in 1992, the staff was thinking big about the power of computing. Gopher and Mosaic and were on the horizon. More prosaically, electronic-format finding aids could be corrected and added to, and printed out anytime (no more liquid white-out) or viewed online – goodbye, paper (well, sort of). The description for the Purviance Family Papers were still described on cards in the card catalog and in a paper box list until a few months ago. As part of a project to make all of our longer legacy descriptions available online, a library intern, Bob Malme, encoded the Purviance Family Papers collection guide – the Rubenstein Library’s 2,000th finding aid. And it is especially fitting that this inventory was the work of one of our interns: an integral part of our library practically since our founding, they have provided a huge amount of support for our collections and their finding aids – in every format.

As a member of the Technical Services Department, whose job it is to crank out all these finding aids, I was – and still am, I guess – an EAD Warrior. That moniker comes from a Duke Special Collections Library group whose early work on standards for Duke online finding aids would shape our goal for total online access for all of our finding aids – cards and paper. How many finding aids will that eventually be? Oh, another 4,000 at least. We’re working on it already!

Post contributed by Paula Jeannet Mangiafico, Senior Processing Archivist.