When I began processing the Charles N. Hunter Papers, I had just completed my work on the N.C. Mutual Collection, which was full of incredible material concerning Durham’s Black business community throughout the 1900s. The Hunter papers constituted a much smaller collection and, as such, I was not prepared to find such a rich and varied amount of information regarding a time period (mainly 1870s-1930s) that is often under-explored and underrepresented in general historical accounts of African Americans in the United States.

The collection paints a broad picture of the evolution of race relations and racial thought during Hunter’s lifetime, including a change in the tone of his beliefs concerning the best way for Blacks to seek equality and dignity within the United States (a change which appears to coincide with increasingly strained race relations in the 1920s). Given Hunter’s extensive experience as an educator in North Carolina, the collection also provides unique insights into the daily workings of the education system for Black children in the post-war, rural South. Additionally, Hunter’s extensive personal correspondence can be found intermingled with the amazing sociological and historical perspectives that are present within his business and community papers. The placement of his personal triumphs and tragedies amidst his professional and community commitments gives his papers a uniquely human dimension. In examining the collection, it was personally difficult for me to see so many personal family tragedies unfold in what seemed like a short period; however, this allowed me to connect with the Hunter by way of seeing the relationship between his public and private life.

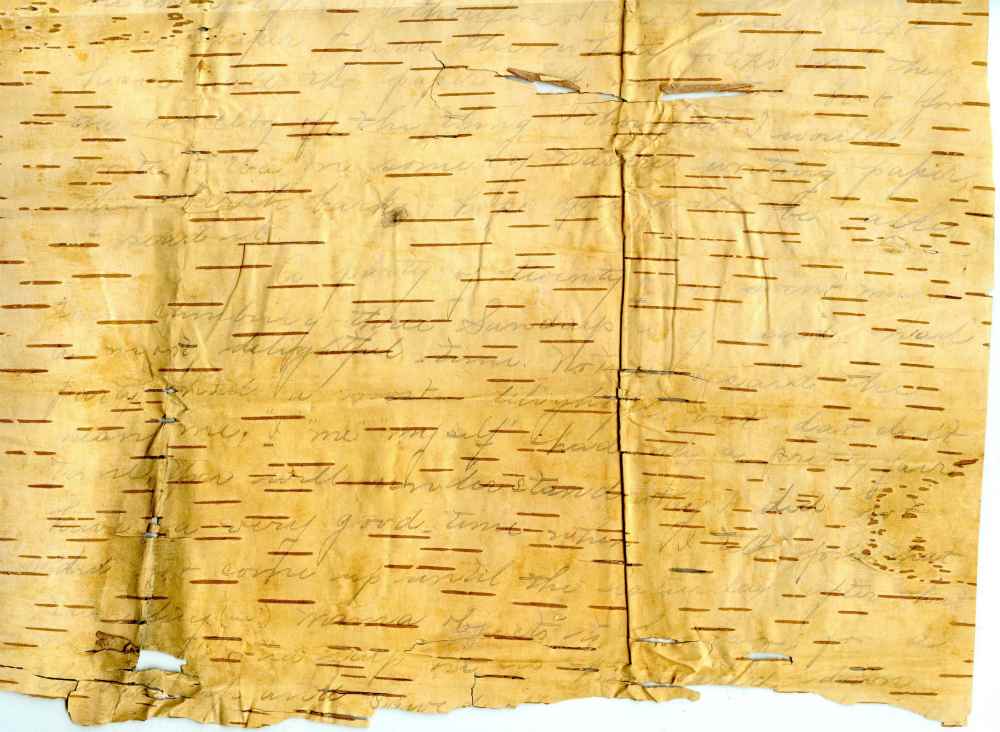

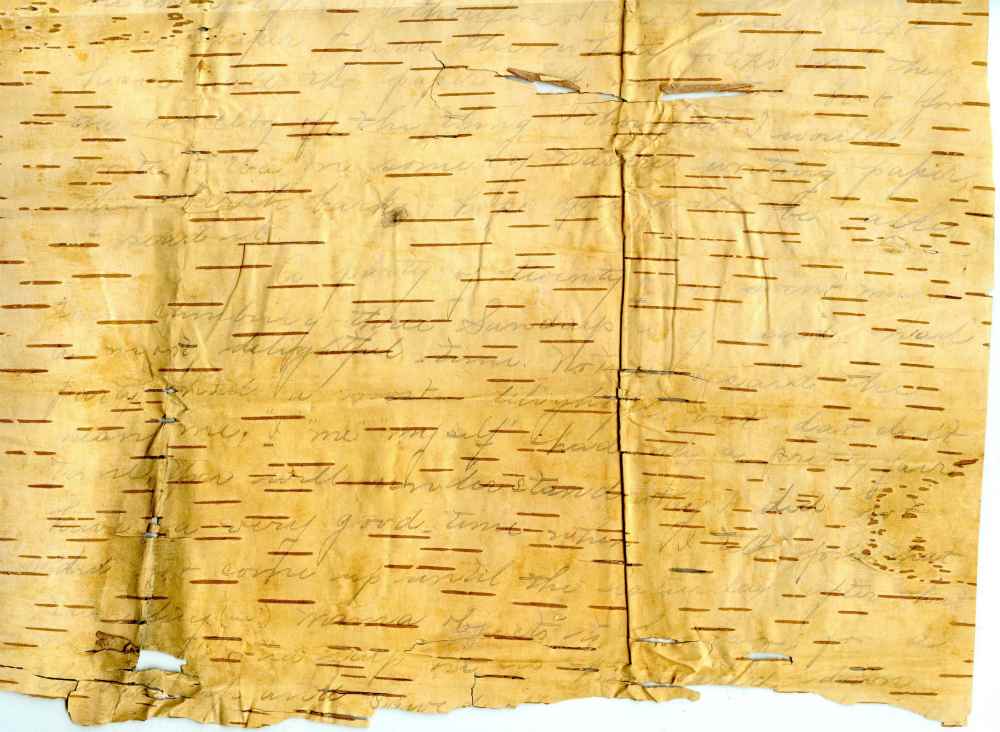

Within the Hunter papers, there are a wide variety of interesting artifacts, some of which include: a letter from a friend written on Birchbark (an amazing piece that is now quite thin and fragile); letters that provide greater elucidation of the daily business aspects of the operation of NC Mutual during the early 1900s; Hunter’s affectionate correspondence with the Haywood family, which owned his family prior to emancipation; and a blank 1850s “Slave Application” for the N.C. Mutual Life Insurance Company of Raleigh.

The latter company is one that was distinct from the N.C. Mutual that began its operations in Durham just before the turn of the 20th century, and the history of the Raleigh company is largely unknown or forgotten. In addition to offering general life and property insurance, N.C. Mutual of Raleigh also allowed slave owners to take out policies covering their slaves for a limited number of years. It is unclear how or when Hunter came by this form, but the presence of this document within the collection brings forth the great irony of both a pre-Civil War N.C. Mutual that insured the lives of slaves and a completely separate post-Civil War N.C. Mutual that was created, owned, and operated solely by former slaves and the children of former slaves.

Post contributed by Jessica Carew, a Ph.D. candidate in the Political Science Department at Duke University and an intern in the John Hope Franklin Research Center for African and African American History and Culture.