Post contributed by Laura Smith, a Doctoral Candidate, History Department at the University of Arkansas. She is a 2019-2020 History of Medicine Collections travel grant recipient.

This question was the starting point for my dissertation research, and it has guided every research trip I have taken in my quest to understand how medical education functioned in the 1800s. The answer? It depends on the time period. In the 19th century, this wasn’t a question easy to answer. People didn’t always trust doctors, and they didn’t really start until medical schools began to provide enough clinical experience for their graduates to consistently produce better health outcomes for patients. I came to Duke to better understand the evolution of clinical experience in medical schools of the 1800s. These pictures trace that history.

Frederick Augustus Davisson went to Lexington, KY in the 1830s on his journey to becoming a physician. He took classes at Transylvania medical school from its most notable professors, Drs. Caldwell and Dudley, men whose publications and work in their communities initially gave Transylvania a decent reputation as far as medical schools went in this era. Davisson took good notes. He recorded the books that were suggested for him to read, books popular at the time.

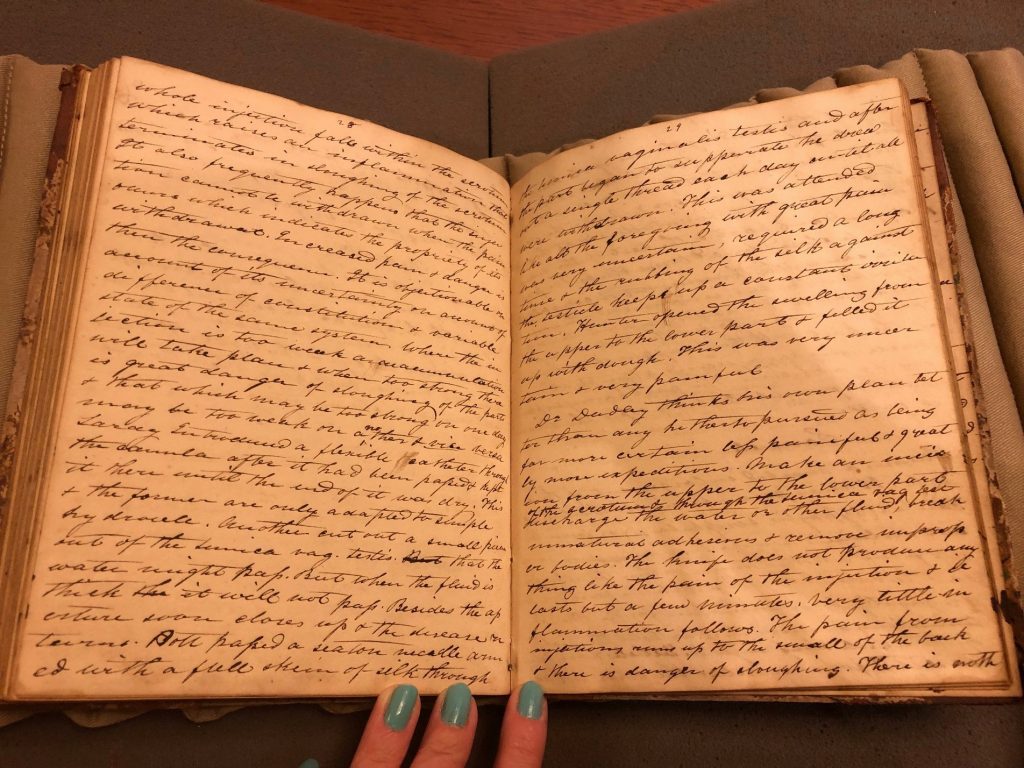

His notes also reflect that medical knowledge in the 1800s was experimental, controversial, and personal as his writings reflect the differing opinions of his professors. “Dr. Dudley thinks his own plan better than any” for treating the retention of fluid in the genitals as it is “far more certain less painful and greatly more expeditious.” Dudley used a knife to drain fluid as opposed to a needle, explaining the benefits of each to his students.

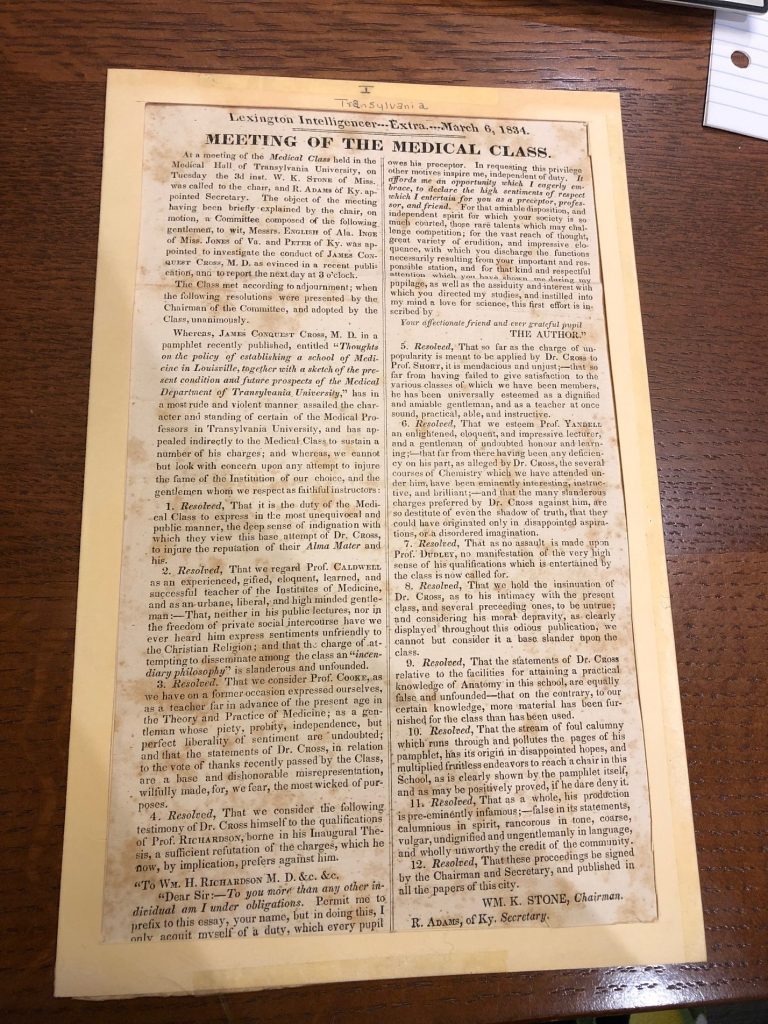

The idea that medical knowledge was not solidified but debated in this era hints that a major challenge to the authority of doctors was surprisingly the slander of other physicians and schools. When Dr. James Conquest Cross, a professor at Transylvania, released a pamphlet on why Louisville, KY needed a medical school, many wondered how another school could be necessary when Lexington already had Transylvania so nearby. In the pamphlet, Cross argued that Transylvania’s school offered no actual experience in hospitals, no dissections, and therefore practiced antiquated medicine. Students improved with the advice of practicing physician-instructors, but nothing compared with the experience of practicing medicine themselves. Questioning the merit of Transylvania, Cross asked, “Who has ever seen a human body opened before the medical class, for pathological purposes? Which of her numerous alumni ever made, a pathological dissection under the eyes of one of her teachers? Of that individual we confess, we are just as ignorant as we are of the inhabitants of the moon.” Until Transylvania aligned with a teaching hospital like a school at Louisville would, it could not graduate credible physicians. The Rubenstein Library’s collections show rebuttal from Transylvania, however. The medical class of 1834 defended their professors, argued they had dissecting experience, and claimed Cross invented lies because of disappointment about being refused a higher position on the faculty. If it’s difficult for us to know who to believe in this debate, it was even more difficult for the public watching this conflict unfold.

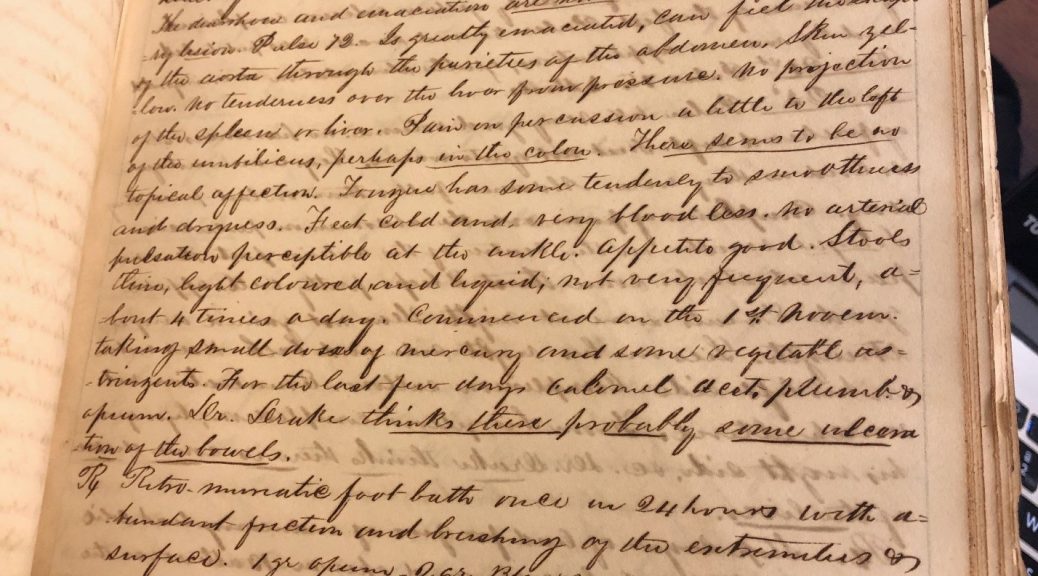

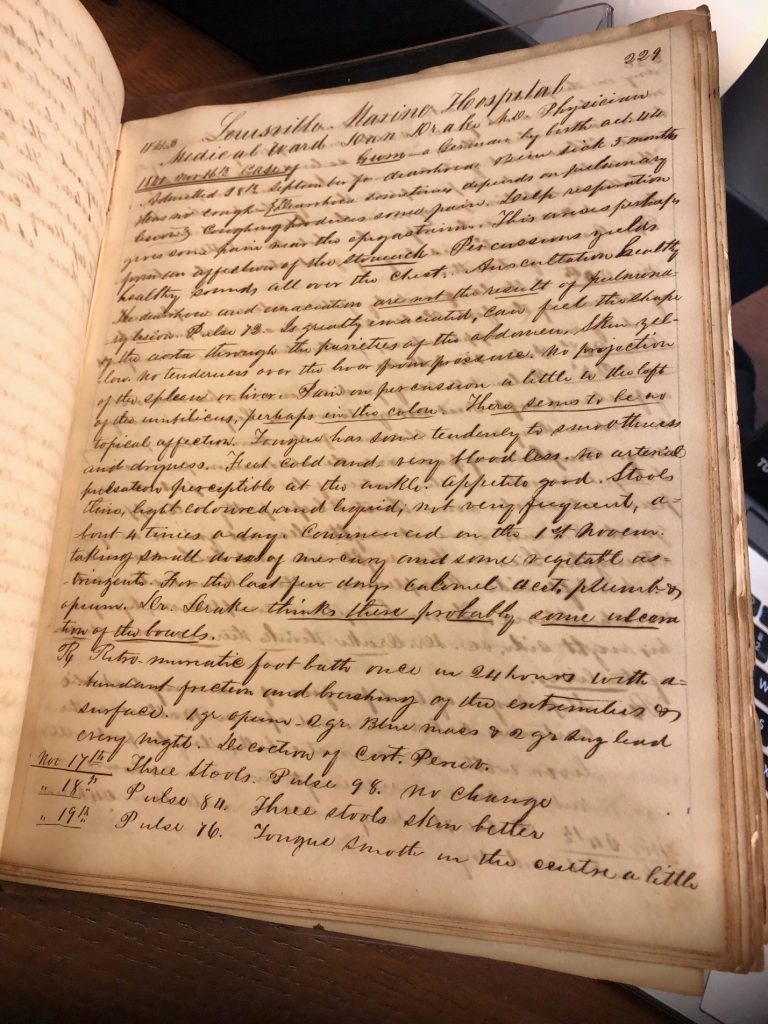

In the end, Louisville did build a medical school. Louisville Medical Institute wooed students with the promise of study in a working hospital, and Duke’s papers from Courtney J. Clark give a rare glimpse into what that early clinical experience looked like. Clark traveled from Alabama to take courses at the Louisville Medical Institute in the same era that Davisson went to Kentucky, and while Clark had similar lecture experience from Kentucky physicians, he also had notes from real cases he studied that Davisson did not. As Clark observed patients in the Louisville Marine Hospital, he learned from his practice, but his work and the work of the LMI faculty also benefitted the poor of the community who could receive low-cost medical care. Clark recorded the prescriptions and health plans of other physicians while closely monitoring the success of patients. When most medical history books praise the progressive teaching methods of Northern schools, these notes show that the medical schools of the US South made clear attempts to give experience while attempting to foster positive relationships with their communities.

This comparison between two Kentucky medical schools through the notebooks of students shed light on how division within the medical community hurt physician trust. Rifts between schools like that between the cities of Lexington and Kentucky turned into ugly and public spectacles partly because for-profit schools competed so intensely for students and prestige. Ironically, long-lasting feuds between schools presented the public with a feeling that doctors could not be trusted as they could not even come to agreement among themselves, and in this way, doctors in the 1800s eroded their own medical authority.

So why do we trust doctors now? We trust doctors because most of us have agreed to trust science and evidence-based conclusions. We trust doctors when they time and again heal us. But perhaps, we also trust doctors because they appear unified, a surprisingly recent development in medical history offering a cautionary tale useful in our own professional and public divisions. Yes, even in 2019.