Post contributed by Hannah Givens, Center for Public History at the University of West Georgia

This post is part of the Dreamers & Dissenters series, in which we highlight Rubenstein Library collections that document the work of activists and social justice organizations. In this series we hope to lend our voices, and those of the people whose collections we preserve, to the reinvigorated spirit of activism across the United States and beyond.

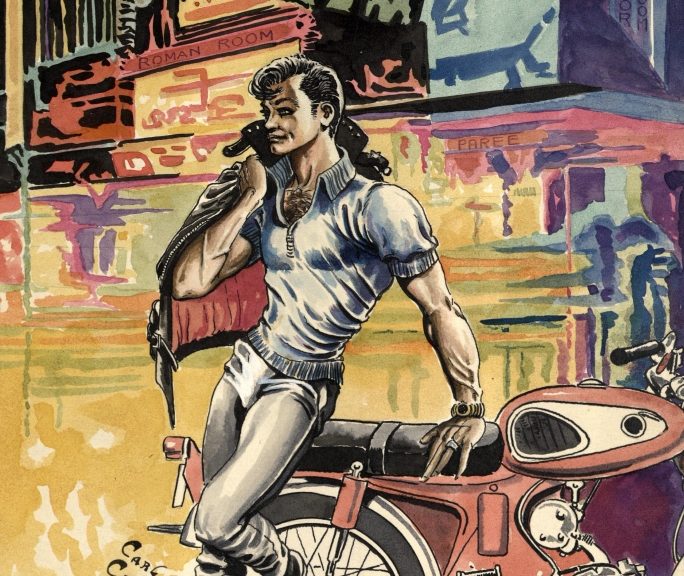

In America, queer history often seems to have “begun” with the Stonewall uprising in 1969, but over the past twenty years, historians have become increasingly interested in pulp fiction as a site of identity and community-building immediately before that. However, pulp novels are often not preserved, their authors remain anonymous or secretive, and their readerships have never been easy to study. Likewise, Southern queer history is a developing field hampered by a widespread misconception that queer history happens only in cities. Southern pulp author and artist Carl Corley serves as a case study that sheds light on both the gay pulp genre and queer Southern history. Corley’s life is well documented in his collection of papers, art, and published books and in the papers of historian John Howard, both held by the Rubenstein Library, as well as in Howard’s landmark book, Men Like That: A Southern Queer History (University of Chicago Press, 1999). A comprehensive digital collection of Corley work is now available online at www.carlcorley.com as the public component of a master’s degree thesis recently completed for the University of West Georgia’s public history program.

As a gay pulp author and artist from Mississippi and Louisiana who published under his own name, Corley is at once a unique and a potentially representative figure. His life and work demonstrate that queer Southerners participated in communities and engaged in a national dialogue about queerness. Corley also challenged readers to accept queer people in society with speeches he included in books like A Lover Mourned (1967):

But in this society, … this love of man for man is not a thing which will last. … Someday, maybe it will last. But not now. It’s impossible. We are doomed and condemned and damned from the start. We are pointed out on the streets, made the butt of ill-timed jokes, ridiculed, and sneered at. There is no place that we can go and hide and live out the burning energy of such a love. We cannot live together with a lover because the law will evict us, and if not the law then the people who are our neighbors.

Corley’s books probably suffered some editorial intervention in the form of tacked-on sad endings, and many of his books contain the usual references to being led astray into a world of homosexual torment. Usually no such event actually happens in the story and overt pro-gay statements substantially outweigh these occasional twilight references. Corley did not shy away from gay-bashing and violence in his plots, but frequently indulged in editorializing on behalf of his characters, explaining that discrimination was the root cause of any perceived misery in gay life. The conclusion of Corley’s highly autobiographical first novel, A Chosen World (1966), is entirely given to this sort of advocacy. Scholars generally assume that readers were savvy enough to simply ignore added moralizing, and thus embrace Corley’s work as empowering.

Corley’s main contribution to the body of gay literature was his rural perspective. He was known for “specializ[ing] in romantic stories about boys from the country,” and his plots show a complex relationship between the country and the city. The mainstream narrative construction for rural queer people is a journey to the city where anonymity allows one to associate with other queer people and come out. However, with a growing academic interest in rural queer studies, a counternarrative has emerged showing how many queer people have lived in rural areas permanently, and that such regions may not be as hostile to queer people as they have been stereotyped. Corley falls somewhere in between. For him the city can be overwhelming, and may contain corrupting influences, but can also offer opportunities and places to meet other queer people. His young rural protagonist frequently makes a trip to the big city (usually Baton Rouge or New Orleans), where he discovers the existence of a queer subculture. However, although some characters stay in the city and begin participating in this culture, many of return to idyllic country life or express regret for leaving. Corley glorifies the rural South as a place where gay couples can be free, happy, dignified, and in harmony with nature, if only their families and neighbors will give them some peace.

While queer activist organizations existed in the 1950s, they were arguably much more secretive than the pulp fandom, and unlike popular fiction they failed to engage queer people where they were, both spatially and socially. They did not attract large numbers of members or subscribers until the 1970s after Stonewall. Also, while activist societies often craved respectability in the 1950s and 1960s, queer media embraced pleasure and desire as part of sexual subjectivity. Many more gay men read pulps than the Mattachine Review, and at the same time, in a time when overt gay themes never appeared on television and rarely in public discourse, the straight mainstream also learned about queer life through pulps. Serious writers like James Baldwin and Christopher Isherwood fit into this loose genre of gay fiction, but these books were hard to find since bookstores and libraries often refused to carry such risqué titles. Cheap, small pulps, on the other hand, had a distribution model based on the magazine trade, shipping directly to outlets like drugstores and train stations, including those in rural areas. As publishers became more reliable, books also came with mail-order forms so customers could purchase them directly from anywhere.

In a sociological survey conducted by Barry M. Dank in 1971, 15% of gay men said they “developed their ideas of what it means to be gay” through reading—a very high percentage compared to the general population of readers. Despite this high number, it is currently impossible to tell exactly how many people were reading pulp novels, how many of them were queer, or how many people read a specific novel or author. Still, comparisons can be made among authors. Corley was popular enough to have three of his novels reprinted in one edition, which suggests a high level of interest. Corley was a recognized author in pulp circles, perhaps a slightly odd one known for rural settings and distinctive covers, but one who contributed to a trend towards establishing gay identity, open sexuality, and demand for respect. Using his own name not only indicates his personal search for literary recognition, but also his status as a successful brand. Corley’s work made rural queerness visible. Although much of his private life remains a mystery, he left behind the most queer-positive work he could in a genre that is only now receiving recognition for the cultural change it helped create.

The cover artwork in this post is awesome. Thank you for sharing !