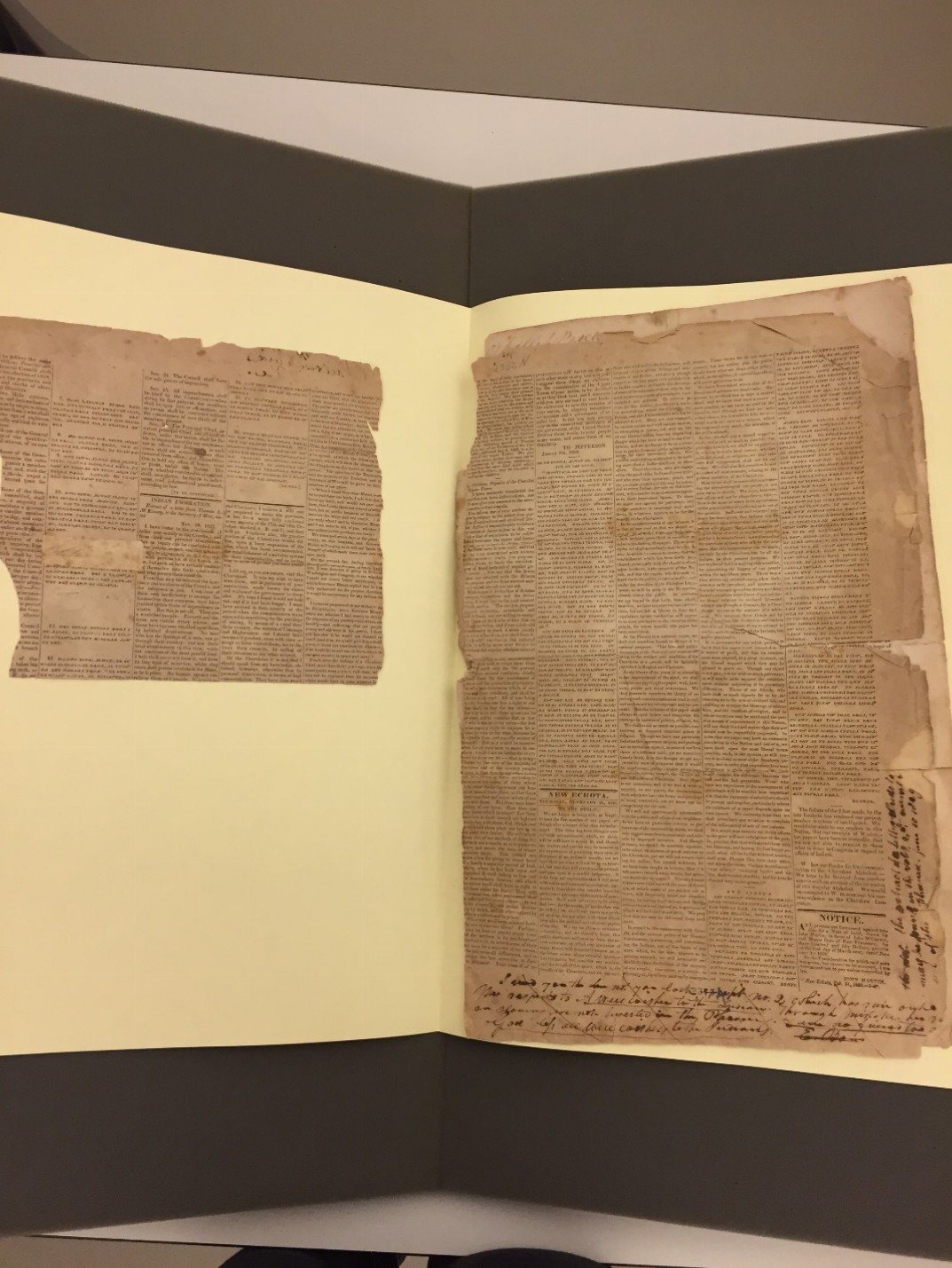

One of the things they don’t tell you in library school is that your personal and professional readings will occasionally overlap—something I’ve found to be especially true as I’ve worked to complete a long gestating newspaper project at the Rubenstein. When I serendipitously encounter primary sources in my readings, I’m forced to ask myself (and occasionally regret asking myself): Does the Rubenstein hold this? In the case of The Cherokee Phoenix, a newspaper written by the Cherokee Nation, the answer turns out to be a resounding yes, and one that I’m glad I pursued.

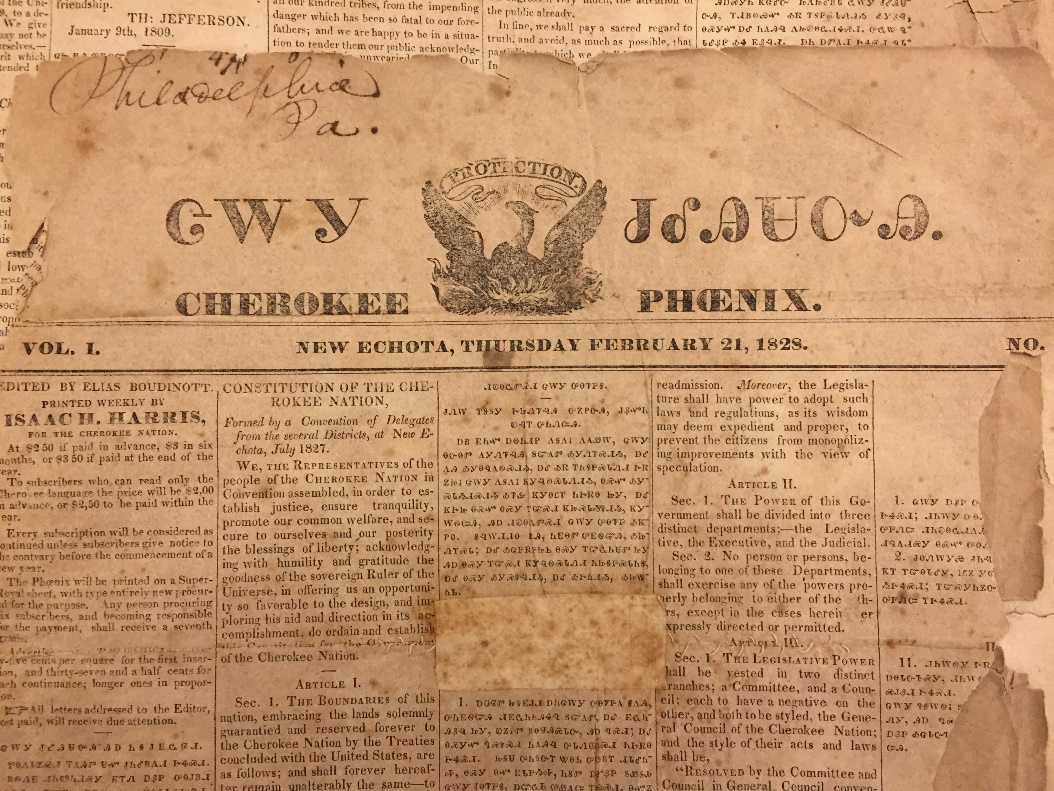

“We, the representatives of the people of the Cherokee Nation in Convention assembled, in order to establish justice, ensure tranquility, promote our common welfare, and secure to ourselves and our posterity the blessings of liberty”—The Constitution of the Cherokee Nation, created in 1827 and published in the first issue of the Cherokee Phoenix.

In the 19th Century, the Cherokee were under attack. Voluntary removals were increasingly involuntary, forcing the Cherokee farther and farther from their homes in the southeast United States. Treaties ostensibly designed to protect the Nation’s lands went unenforced by the state and federal governments (Zinn, 2015, p.143-148) (Brannon, 2005, p.14). And in 1830, Andrew Jackson signed the Indian Removal Act into law, thereby granting the federal government power to forcibly migrate Native Americans into lands beyond Mississippi (Primary documents in American history). The Cherokee were subsequently “rounded up and crowded into stockades” in October 1838 and made to march (Zinn, 2015, p.148). Today we recognize this as the start of the Trail of Tears, a cataclysmic event resulting in the deaths of some 4,000 Cherokees (Primary documents in American history).

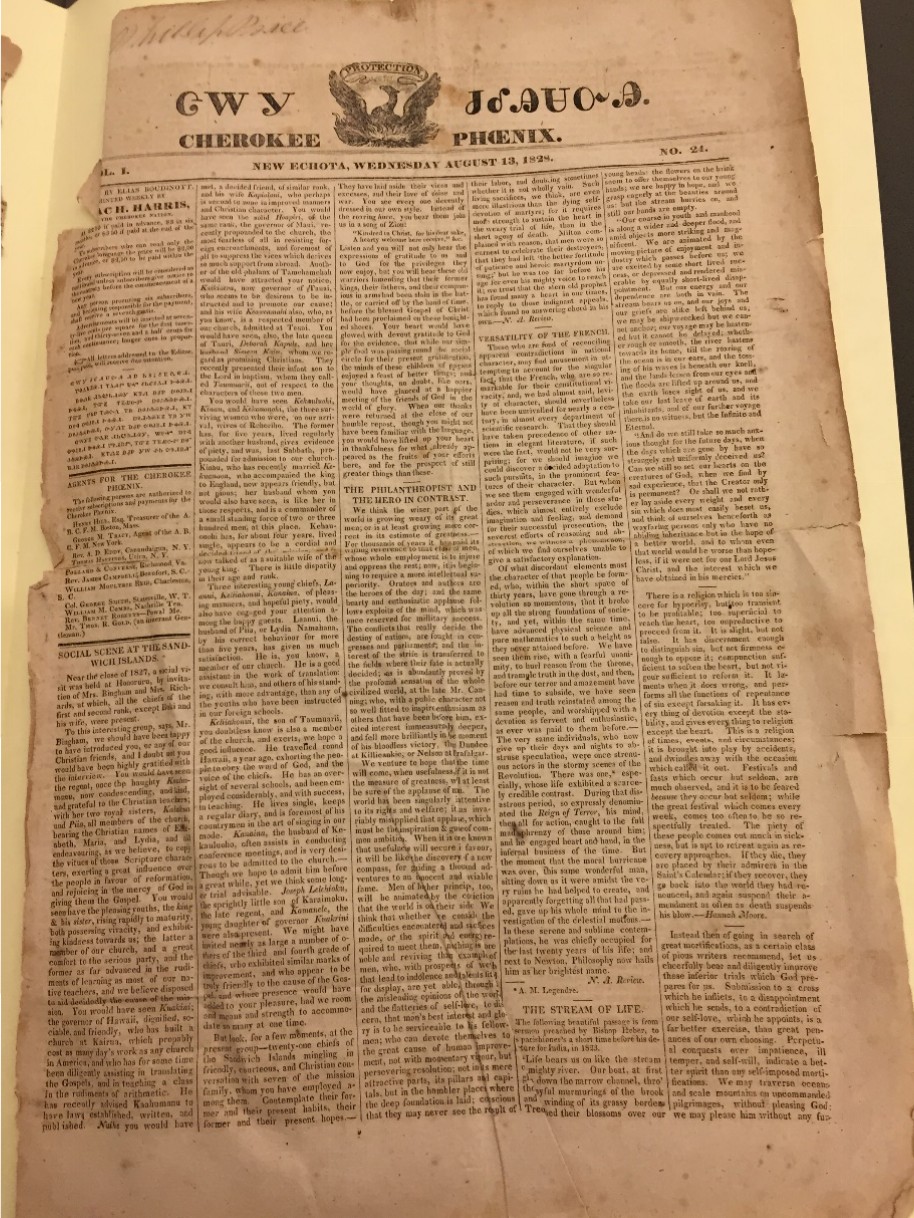

The Cherokee Phoenix, a newspaper first published by Isaac H. Harris on February 21, 1828, navigates this sliver of time in the history of the Cherokee Nation, a time in which it fought to maintain its lands, protect its people, and keep its ways of life. In the first issue, the editor, Elias Boudinot, juxtaposes the opening salvos of the recently written (1827!) Constitution of the Cherokee Nation with a letter written by Thomas L. McKinney to the Secretary of War about the Cherokee people. A public notice underlining the difficulties in creating the paper and a column critical of the Federal government can also be found. The Cherokee Phoenix thus proves to be a remarkable historical document, made all the more remarkable by the fact it’s written in both English and Cherokee—a language that did not have a written component until 1821 (Brannon, 2005, p. x).

The Cherokee syllabary was created by Sequoyah, a silversmith and trader by profession, who felt that written language could be harnessed and used to the Cherokee’s advantage. In his initial attempts, Sequoyah tried to create a “symbol for each word in the language,” but that soon proved insufficient, and he turned his attention to the sounds of the language, paying particular attention to the syllables (Sequoyah and the Cherokee Syllabary). Eventually, he was able to isolate 85 syllables and devise associated symbols that could be combined to create a written component of the Cherokee language. The first to learn how to read and write using this syllabary was Sequoyah’s daughter, A-Yo-Ka. Incredibly, in eleven years, Sequoyah’s efforts proved successful: he developed an entirely new means of communication for his Nation. By 1825, there were Cherokee translations of hymns and the Bible, and thousands of Cherokee were literate (Sequoyah’s syllabary) (Sequoyah and the Cherokee Syllabary).

Three years later, the Cherokee nation purchased its own press and began publishing the Cherokee Phoenix in New Echota Georgia, the capital of the Cherokee Nation. The type was cast by Reverend Samuel Worcester, a missionary, postmaster, and now printer (Samuel Worcester). Forty-seven issues were published under its original name. And now, almost 200 years later, the Cherokee Phoenix name is still in use: The Cherokee Nation publishes both online and print editions of the newspaper, with a subscription base of 40,000 readers (Cherokee Phoenix celebrates 184 years).

Sources:

Brannon, F. (2005). Cherokee phoenix, advent of a newspaper: The print shop of the Cherokee Nation 1828-1834, with a chronology. Tuscaloosa, Ala.: SpeakEasy Press.

Cherokee Phoenix celebrates 184 years. (2012, February 21). Cherokee Phoenix. Retrieved May 3, 2016, from http://www.cherokeephoenix.org/

Primary Documents in American History. (n.d.). Retrieved May 03, 2016, from https://www.loc.gov/rr/program/bib/ourdocs/Indian.html

Samuel Worcester. (n.d.). Retrieved May 03, 2016, from http://www.cherokee.org/AboutTheNation/History/Biographies/SamuelWorcester.aspx

Sequoyah and the Cherokee Syllabary. (n.d.). Retrieved May 03, 2016, from http://www.cherokee.org/AboutTheNation/History/Facts/SequoyahandtheCherokeeSyllabary.aspx

Sequoyah Museum: Sequoyah’s Syllabary. (n.d.). Retrieved May 03, 2016, from http://www.sequoyahmuseum.org/index.cfm/m/6

Zinn, H. (2015). A People’s History of the United States (Reissue ed.). New York, NY: Harper Perennial Modern Classics.

Post contributed by Liz Adams, Special Collections Cataloger.