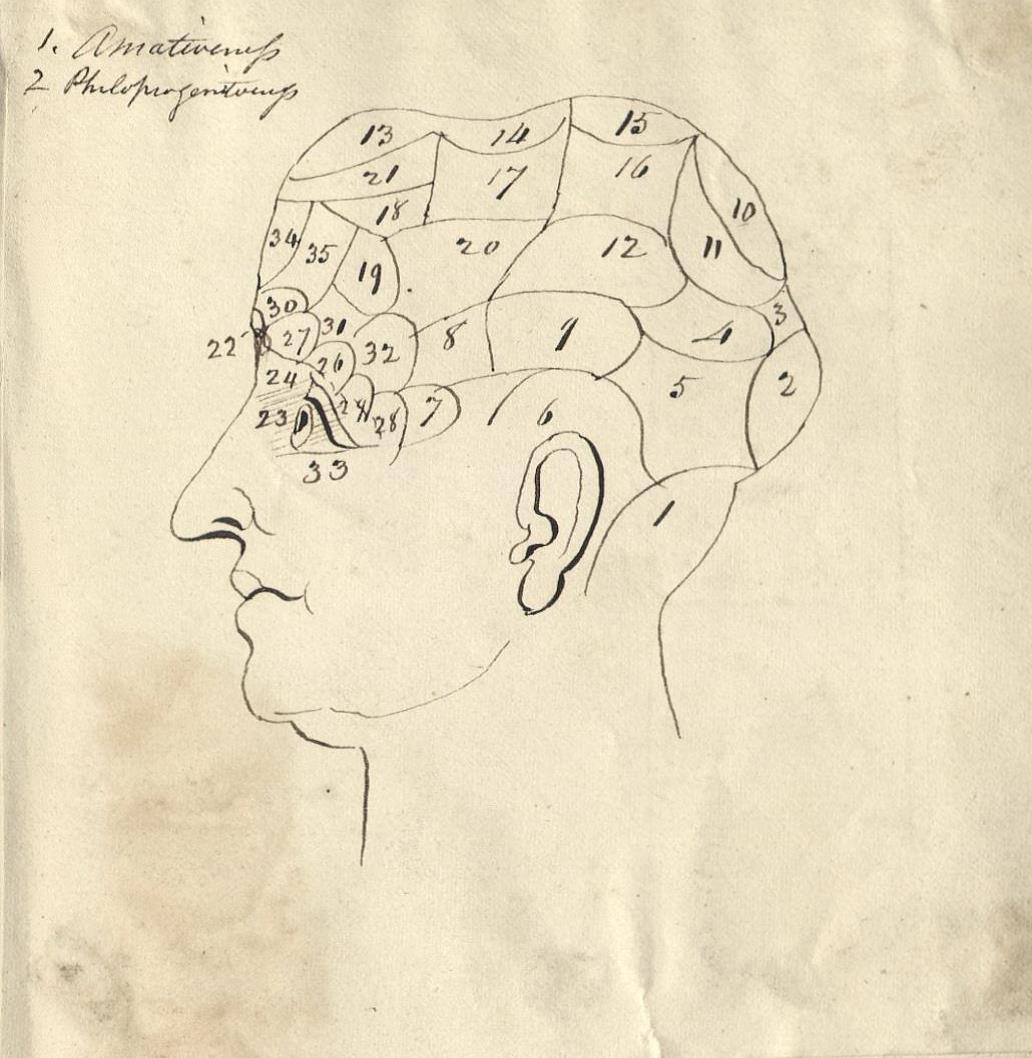

The image above, taken from the commonplace book of E. Bradford Todd (found in the Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library), is representative of a popular view of the science of phrenology. Seen today on ironic posters and T-shirts, as well as modern ceramic reproductions, the phrenological bust has come to serve as metonym for the entire science of phrenology. The image persists, but so too do misconceptions about the nature of this peculiar nineteenth-century science, which proposed to articulate and even predict the character of an individual based on the shape of the skull.

Phrenology was attractive to the masses and inspired writing of all kinds, from diary entries to letters, as well as published texts and broadsides. E. Bradford Todd, as shown above, recorded the phrenological doctrine – complete with his own sketches – into his commonplace book in mid-nineteenth-century America. Eugene Marshall, a schoolteacher in 1851 in Rhode Island, went to see a phrenological lecture and resolved to study the science, a project he took on with such zeal that he eventually attempted to phrenologize himself. Writing in 1823 when the science was still young, another individual gossiped to a friend via letter that a mutual acquaintance was looking for a wife “with all the proper bumps on her head for he is a great believer [of phrenology]” (Eliza K. Nelson papers). As seen in these letters and diaries from Duke University’s Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library, from its earliest introduction, phrenology captured the mind of the public and promised solutions to life’s problems, both great and small, not least of which was the problem of crime.

With generous assistance from the History of Medicine travel grant, I recently visited the Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library to conduct research in support of my dissertation, “Criminal Minds: Law, Medicine, and the Phrenological Impulse in America, 1830-1890.” My research takes a serious look at the “pseudoscience” of phrenology and considers the ways in which it was viewed as truthful, scientific, and useful to nineteenth-century individuals. In particular, I examine how phrenology, at the beginning of the century, came to be viewed as a valuable possibility for crafting a criminal science avant la letter, more than half a century before the introduction of Cesare Lombroso’s positivist criminology that would later be considered the birth of modern criminology.

Phrenologists wrote early and often about the problem of crime, which was drawing attention from all corners in the nineteenth century. The growth of cities and urbanization, the increasing rapidity and ease of movement of peoples within and between countries, and the rise of mass media that made sensational stories about murder and theft national (and international) news – all of these nineteenth-century trends combined to render crime a particularly fraught problem. Yet well before “criminology” had been introduced, phrenologists and other enthusiasts were considering the ways in which this new science could be used to help solve crime.

While it was primarily intellectuals and professional phrenologists operating within a narrow orbit who ruminated on the potential of phrenology with regard to the criminal problem, we can also find glimpses of the reception of these ideas in the records of non-phrenologists who encountered the science. For example, in the diary of Jane Roberts, a British author, she records a trip on January 6, 1837, to visit a phrenologist in London, Dr. DeVille, with her friend Mrs. Phillips, Lord Byron’s daughter. During this visit, both received phrenological readings by DeVille, but they also heard a long discourse from him about the truth of the science. Interestingly, the examples DeVille chooses to illustrate and prove the science are linked directly to bad behavior and crime, explaining that attention to the developments of the mind (as read in the skull) can serve to prevent or cure evil propensities. He illustrates this claim with two examples: one story in which he identified two robbers before the fact, and a second where a father brings his son in to see DeVille, before he eventually is sent to prison for his crimes. Miss Roberts was impressed by these stories, and resolved to visit him again.

Whether or not Miss Roberts repeated her pilgrimage to the phrenologist’s office, this interaction is representative of the ways in which phrenological ideas about crime entered into vernacular culture. Phrenologists framed their enterprise as a solution to one of the era’s most pressing problems, in part to sell their services to individuals like Miss Roberts. Yet, as I argue, phrenology also made a clear claim attempted to predict and explain the behavior of criminals, and in so doing signaled the development of a new science of crime.

Courtney Thompson is a PhD candidate in the History of Science and Medicine Program, History, at Yale University