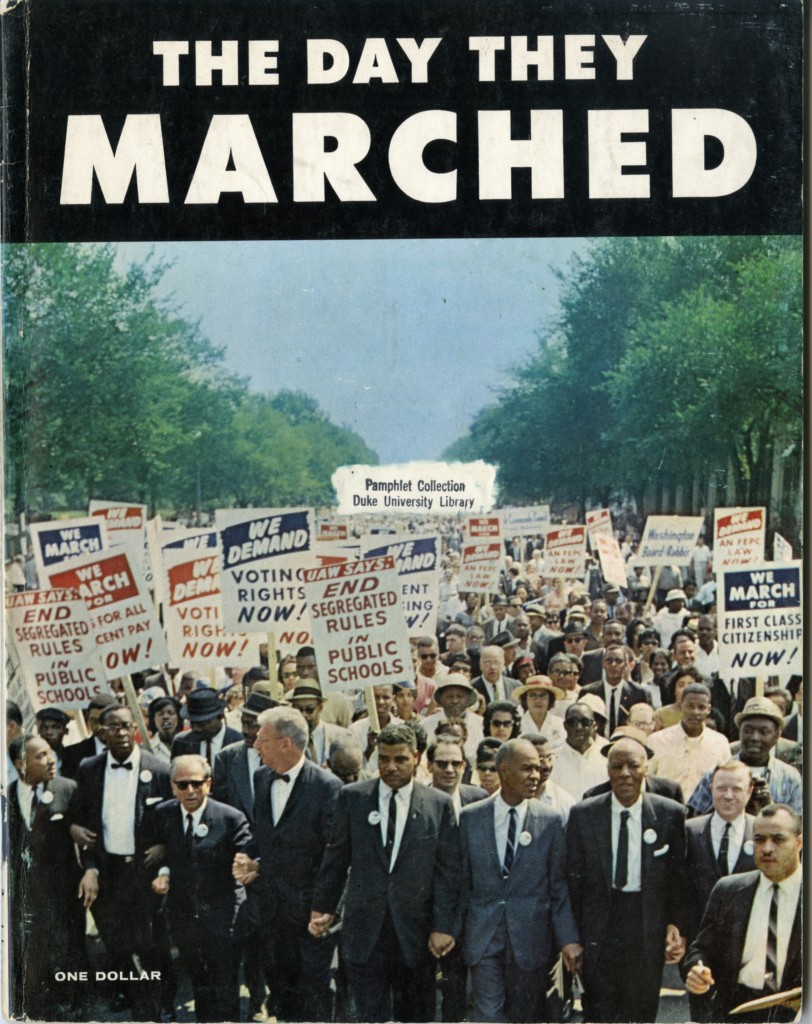

As the nation pauses and acknowledges the 50th anniversary of the August 28, 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, it is important to remember that this was not the first African American organized mass march movement on the National Mall. The leaders of the March on Washington of ’63, Bayard Rustin, Andrew Young, Roy Wilkins, and others, used a blueprint established by another notable African American leader, A. Phillip Randolph, only a generation before them.

While serving as head of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, Randolph proposed a March on Washington on July 1, 1941 to protest the lack of opportunities given to African Americans in a recovering American economy. As World War II waged in Europe and Asia, American industry saw remarkable growth as suppliers of arms and supplies to their diplomatic allies, but African Americans were largely shut out of both federal and private jobs. Randolph believed that a march on the nation’s capital would provide a stage to give voice to African Americans suffering from both economic and social prejudice. As the March on Washington movement grew, Randolph threatened President Franklin Roosevelt that close to 100,000 people would descend on the nation’s capital if change did not occur. The March was ultimately called off by Randolph after Roosevelt passed Executive Order 8801, ordering the prohibition of discrimination in defense industries.

While serving as head of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, Randolph proposed a March on Washington on July 1, 1941 to protest the lack of opportunities given to African Americans in a recovering American economy. As World War II waged in Europe and Asia, American industry saw remarkable growth as suppliers of arms and supplies to their diplomatic allies, but African Americans were largely shut out of both federal and private jobs. Randolph believed that a march on the nation’s capital would provide a stage to give voice to African Americans suffering from both economic and social prejudice. As the March on Washington movement grew, Randolph threatened President Franklin Roosevelt that close to 100,000 people would descend on the nation’s capital if change did not occur. The March was ultimately called off by Randolph after Roosevelt passed Executive Order 8801, ordering the prohibition of discrimination in defense industries.

Albert Parker’s Negroes March on Washington (1941) and The March on Washington, One Year After (1942), recount the MOW movement from that time. Parker, a staunch socialist, was indeed excited at the prospects of the March in 1941 and continual organization of African Americans against the federal government. But his 1942 publication reflected disappointment with Randolph’s actions in cancelling the march and acceptance of the Executive Order that was slow to desegregate the military and open jobs in the private sector.

Albert Parker’s Negroes March on Washington (1941) and The March on Washington, One Year After (1942), recount the MOW movement from that time. Parker, a staunch socialist, was indeed excited at the prospects of the March in 1941 and continual organization of African Americans against the federal government. But his 1942 publication reflected disappointment with Randolph’s actions in cancelling the march and acceptance of the Executive Order that was slow to desegregate the military and open jobs in the private sector.

Post contributed by John Gartrell, John Hope Franklin Research Center Director.