Occasionally we are asked to disbind books. Sometimes that is an easy task, but when it comes to library-bound serials from the mid 1980’s it isn’t so easy.

Library binding is a specific process, there is even a NISO Standard for it. It’s a tough, made-to-last binding that includes sewing signatures around sawn-in cords, gluing the spine and applying a heavy spine lining, and creating a cover of heavy boards and durable buckram cloth. I love library bindings, they are indestructible by design and have a utilitarian-ness about them.

Library binding is a specific process, there is even a NISO Standard for it. It’s a tough, made-to-last binding that includes sewing signatures around sawn-in cords, gluing the spine and applying a heavy spine lining, and creating a cover of heavy boards and durable buckram cloth. I love library bindings, they are indestructible by design and have a utilitarian-ness about them.

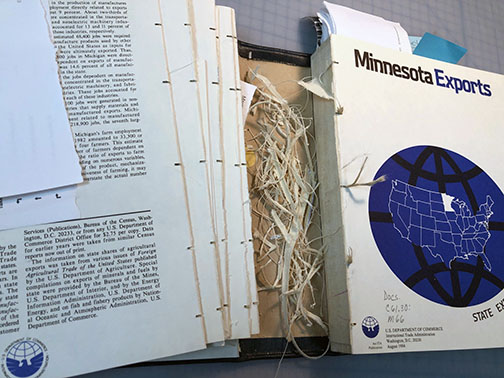

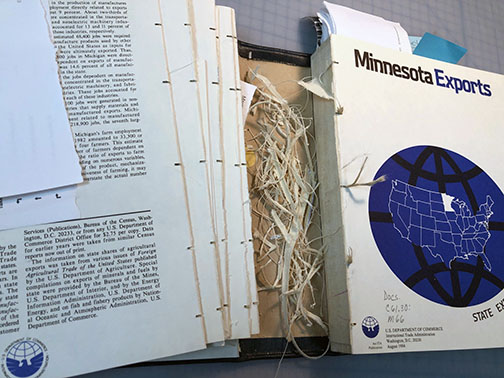

But when you have to take one apart it can be challenging, and time consuming. Cutting the threads and carefully cutting through the spine lining between issues takes patience. There is always some damage that must be repaired later. The paper scarfs, or your knife slips and cuts the outer folio.

But when you have to take one apart it can be challenging, and time consuming. Cutting the threads and carefully cutting through the spine lining between issues takes patience. There is always some damage that must be repaired later. The paper scarfs, or your knife slips and cuts the outer folio.

Issue by issue I take it apart. I see the small knots in the thread where the person who sewed this added a new piece so she could keep going. It took time to bind this, and it was probably one of a thousand books that she bound that year.

Issue by issue I take it apart. I see the small knots in the thread where the person who sewed this added a new piece so she could keep going. It took time to bind this, and it was probably one of a thousand books that she bound that year.

The evidence of her hand is a reminder that a skilled trades person put this together. Her sewing is still tight. She made that small knot, trimmed it carefully, and kept going until she had a three-inch thick volume sewn together, ready for casing in. Taking this apart is a reminder that not everything we do in Conservation is permanent. Sometimes we undo hours of care and labor. I honor the labor that it took to create this volume, even as I take it apart, smiling at each small knot I come across.

The evidence of her hand is a reminder that a skilled trades person put this together. Her sewing is still tight. She made that small knot, trimmed it carefully, and kept going until she had a three-inch thick volume sewn together, ready for casing in. Taking this apart is a reminder that not everything we do in Conservation is permanent. Sometimes we undo hours of care and labor. I honor the labor that it took to create this volume, even as I take it apart, smiling at each small knot I come across.