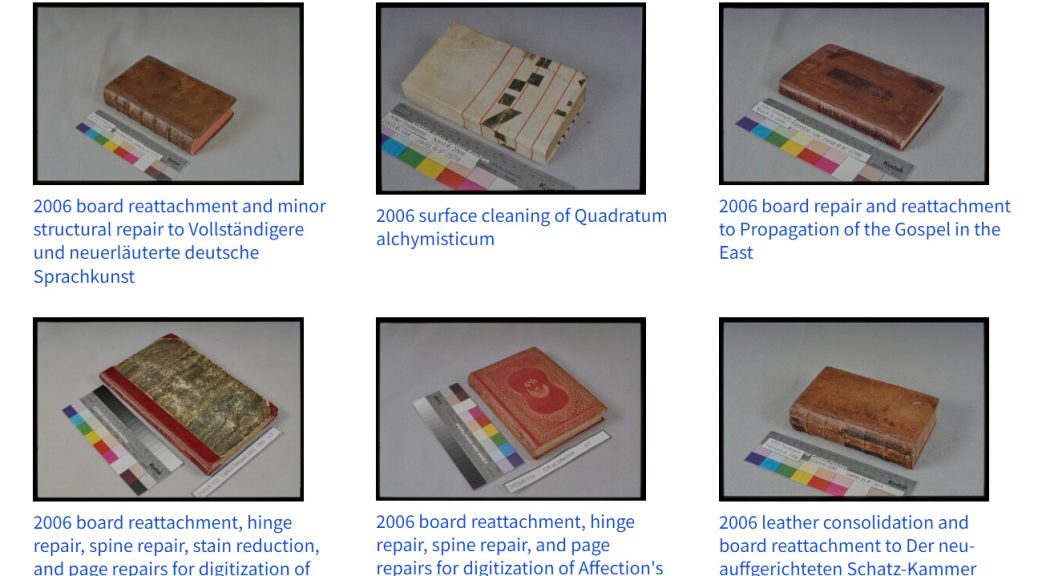

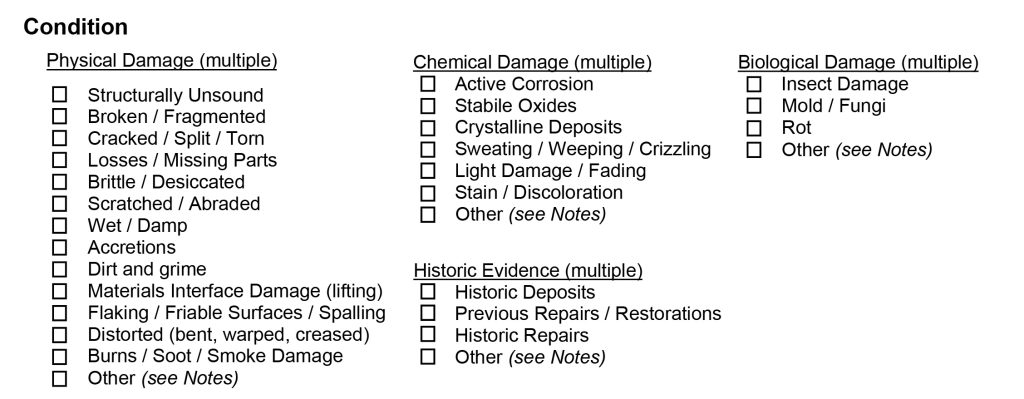

Today we are excited to publicly announce the launch of The Conservation Documentation Archive (CDA). This is the culmination of several years of work to digitize and make available all of the conservation documentation that has been produced as part of caring for Duke’s collections for the last 26 years. Over 1400 records have been ingested into the Duke Digital Repository at this point, with smaller batches of records expected to be added annually. This work was generously supported by a 2021 Lyrasis Catalyst Fund grant and was awarded the inaugural Sandy Nyberg Award. We hope that this archive will become a valuable resource, not only for researchers to access additional information about objects in the collection, but in documenting the standard preservation practices of our institution and the profession at large. A great deal of thought and effort went into building the CDA, so over the coming months we will publish a series of blog posts discussing in greater detail some of our motivations and processes for creating this repository collection.

In the first installment, we will travel back to February 2020, when staff from Conservation Services began discussing this project, to examine the scope of records that needed to be digitized and problems that the CDA is attempting to address.

Readers who are unfamiliar with the details of our work may be asking, “What is all this documentation and why do we need to save it?” The rationale for creating and maintaining documentation is laid out in The American Institute for Conservation’s Guidelines for Practice (see numbers 24-28), one of the core guiding documents for our profession. The purpose of this documentation is to be an accurate and permanent record of our examination, testing, and treatment for any of the objects that come under our care. This could be when an item will be altered as part of conservation treatment, but documentation is often created for condition assessments, like collection surveys or prior to an exhibit loan. Our records attempt to describe the collection material, establish its condition at the time of examination, and help future custodians in their work with the item. When possible, the records we create include both written reports and images.

The format and detail of the treatment reports has varied considerably over the years, depending on the type of object or collection, circumstances, and who produced it. Most of our records were produced by department staff over the years, but some of the records come from vendors or conservators in private practice. Reports typically start with a number of basic fields with identifying information from the catalog or finding aid and name of the examiner and a date for the report. The item’s dimensions are measured and recorded on the form. The report might also include a statement about the justification or goals for treatment.

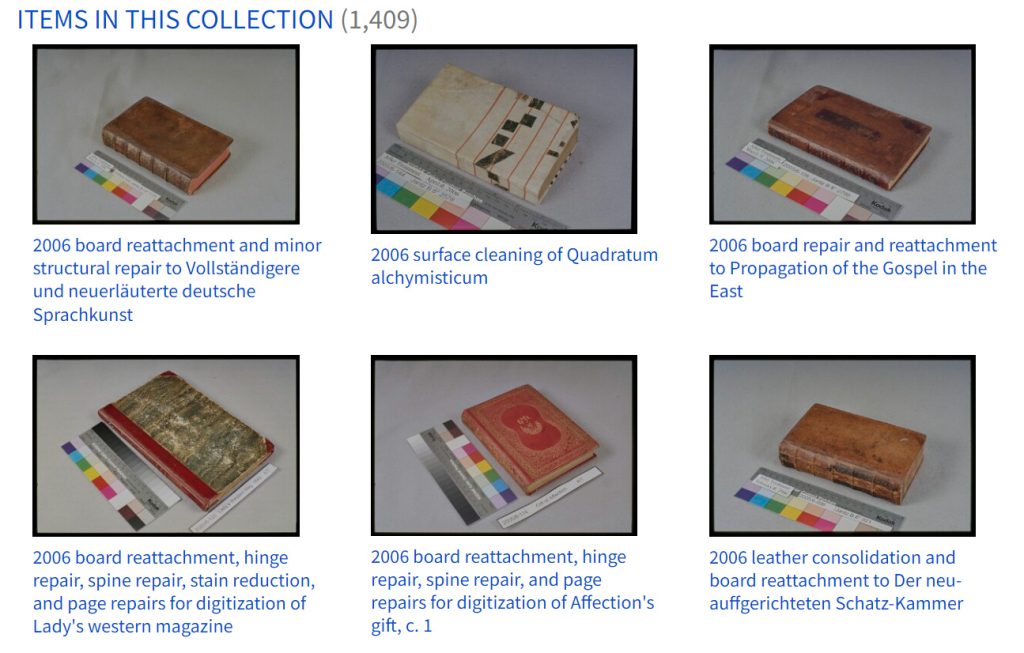

Next we try to thoroughly describe the object (and accompanying items), including the format, structure, style, and decoration. The report includes what materials are used and if there are any distinguishing characteristics or marks. We also try to capture any condition issues that are observed, including damage or degradation, evidence of past treatment, and risks of additional damage or loss from use. We will note the methods of examination, including any testing and their results. This information informs our proposal for treatment.

The proposal for treatment is often a list of potential options, ranging from minimal intervention to very extensive treatment. We typically list the materials we will use, any alternative approaches that might be possible, and the potential risks. The proposal will include an estimate for the treatment time to help with setting priorities and workload. At this stage in the process, we will hold a meeting with the collection curator and other stakeholders to discuss the various treatment options and arrive at the best course of action for the item. This section of the report includes space to document the date of the meeting, the names of staff in attendance, and signatures of the conservator and curator or collection manager.

The remainder of the report describes the treatment itself, such as procedures or techniques and the location and extent of all alterations. If the treatment carried out is in any way different from the proposal, we will note why. This section documents any material that may have been added or removed, including the manufacturer or source for added materials. We list any adhesives or other substances (cleaning agents, solvents, poultices, etc) used in the treatment, including their chemical name and manufacturing source. This information will be most helpful if the item needs treatment again in the future or if any of the alterations need to be reversed for some reason. The date the treatment was completed and the time spent are also recorded here.

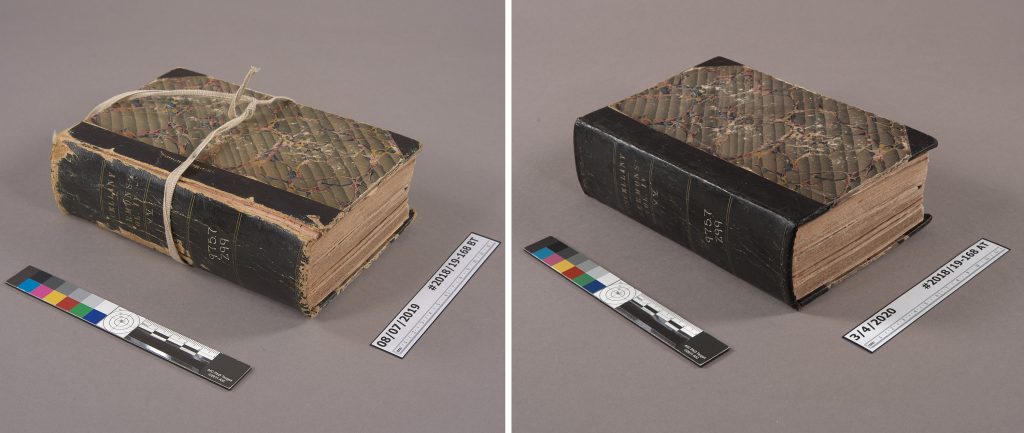

We produce photographs of the item before any alterations are made and after treatment is complete. In some cases we will photograph the object during treatment, too. We follow the AIC Guide to Digital Photography and Conservation Documentation for our photography workflow. The photographs typically show the item positioned on a neutral gray backdrop and include a target or photo checker card and printed label. The target or color checker provides a standard of comparison to help capture scale, direction of illumination, and true color of the item. These targets help us to create consistent before and after images, so that one can more easily compare the changes that occurred during treatment. The label in the photo includes a unique identifier for the item (the lab log number) and date of the photograph. This practice ensures we can always identify the item in the photograph, even if the file names or image metadata are altered or erased.

Conservation Services has been storing legacy documentation produced over the last 26 years in a large filing cabinet. The records for each treatment reside in their own paper file folder. The formats and media of those records have changed with the available technology. In addition to paper reports, our archive of physical media contains 35mm color slides, and inkjet photographic prints. The born-digital documentation is saved in a variety of file formats on networked storage. Reports tend to be saved in Microsoft Word or PDF format, while the images are saved in an archival raw format (DNG), as well as derivative TIFF and JPG versions. The TIFF acts as a preservation-friendly file format, while the JPG is a compressed format that is much easier to scroll through or post on the web. We have been printing paper copies of the forms and representative images as a backup for several years. Some of the older treatment folders hold very small fragments (like remnants of original sewing thread) that could not be reincorporated into the object during treatment. Our current practice is to encapsulate small fragments and store them in the enclosure with the item.

The conservation documentation that we produce has enduring value for both collections research and the history of the library. One of the key principles of the Duke University Libraries Strategic Plan is support and advocacy for openness. Our department has always made our records available to anyone who asked (assuming that access respects donor agreements for restricted collections and confidentiality), but previously there hasn’t been a good mechanism for researchers to know that an item has been treated or that these records exist. Library staff in other departments may not even be aware that we have a cabinet full of reports sitting in our lab.

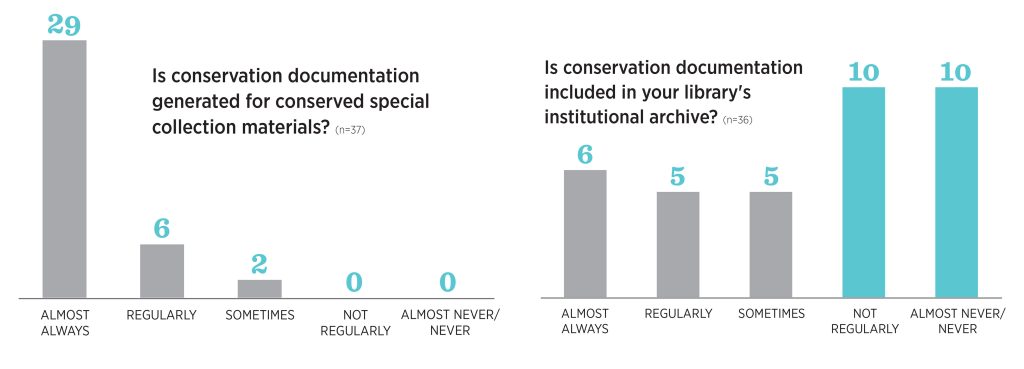

This is a fairly common situation across our peer institutions. A 2012 survey by Laura McCann at NYU Libraries indicated that a majority of conservators at research libraries are producing documentation for special collections treatments, but fewer than half are depositing those records into the institution’s archives. Maintaining records of previous treatments is important for making decisions about the item’s care in the future. It also becomes an important record if an item is lost, destroyed in an accident, or becomes inaccessible for other reasons. Improved access to our documentation might help us to evaluate different treatment methods or materials. It might also aid future scholarship into the history of the conservation profession, providing a record of accepted practices for different time periods, and giving more context to our thought processes and rationales for certain treatment decisions.

With this summary of what we are trying to preserve and why out of the way, next we will look at some of the work that went into digitizing the legacy records and creating the necessary metadata for ingesting everything into the Duke Digital Repository. We’ll be taking a break from blogging in December, so look for our next installment in January 2024.

References:

- American Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works. (1994). Code of ethics and guidelines for practice (pp. 6-10). https://www.culturalheritage.org/docs/default-source/resources/governance/organizational-documents/code-of-ethics-and-guidelines-for-practice.pdf

- American Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works. (2008). Commentaries to the guidelines for practice of the American Institute for Conservation of Historic & Artistic Works. https://www.culturalheritage.org/docs/default-source/resources/governance/organizational-documents/commentaries-to-the-guidelines.pdf

- Frey, F. S., Warda, J., & Digital Photographic Documentation Task Force. (2011). The AIC guide to digital photography and conservation documentation. American Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works.

- McCann, L. (2012, May 8-11). Documentation at risk? Conservation documentation practices in academic research libraries [Poster presentation]. American Institute for Conservation, Albuquerque, New Mexico. https://www.culturalheritage.org/docs/default-source/publications/annualmeeting/2012-posters/8-conservationdocumentation.pdf