As readers may remember we had a painting at Lilly Library spontaneously fall off the wall this summer while we were all working from home. The painting’s hanging wire was very brittle and snapped. It’s difficult to say whether it snapped first then fell, or broke on the way down as it snagged on the hook. Regardless, we started worrying about the wires on the Duke Family Portraits that hung high above the reference desk, and whether those, too, were in danger of falling. After consultation with Lilly and library administration, we decided we needed to remove these before the semester began and before people were in the building again.

Needless to say this was not an easy endeavor. It took staff from Lilly, Conservation, LSC, Shipping and Receiving, Cataloging, and art handlers to make it happen. Here’s a visual play by play of the action. Click on the images for a larger view.

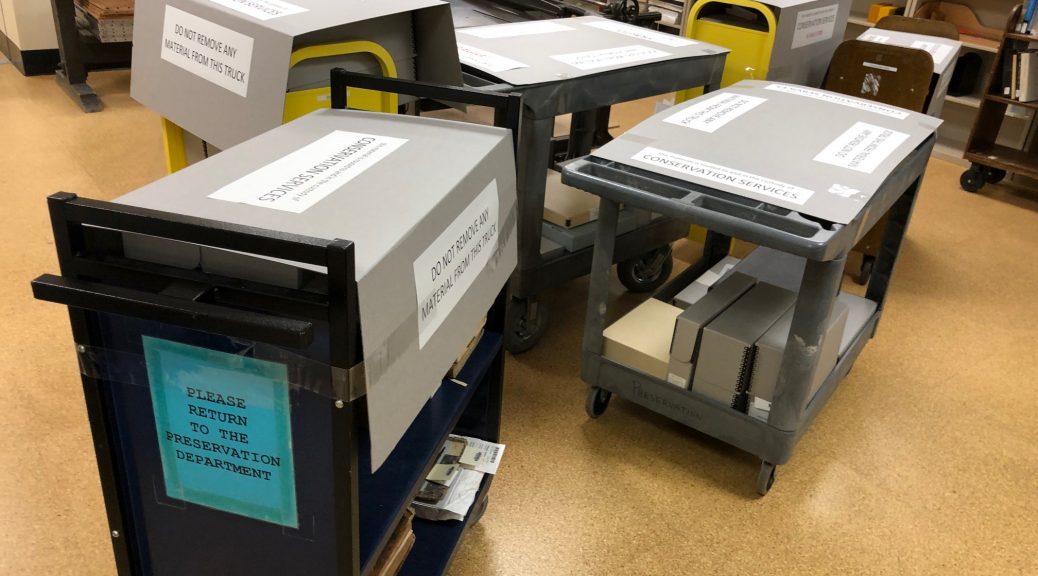

The first step was for our vendor to fabricate crates for each painting. Those were made and delivered to Lilly.

The “travel” crates have wood frames with corrugated coroplast sides to lighten the weight of the crates. Each painting ranges from 48″ wide to 73″ tall and 3″ deep. So every ounce counts with crates this size.

Next step was to get them off the wall and this required a small two-person lift. We had to temporarily remove the security gate to get it in through the front door.

|

|

|

Before crating we wanted to vacuum the decades of dust off the frames and paintings. While Rachel vacuumed, Peter and his crew kept removing paintings from the wall.

|

|

|

|

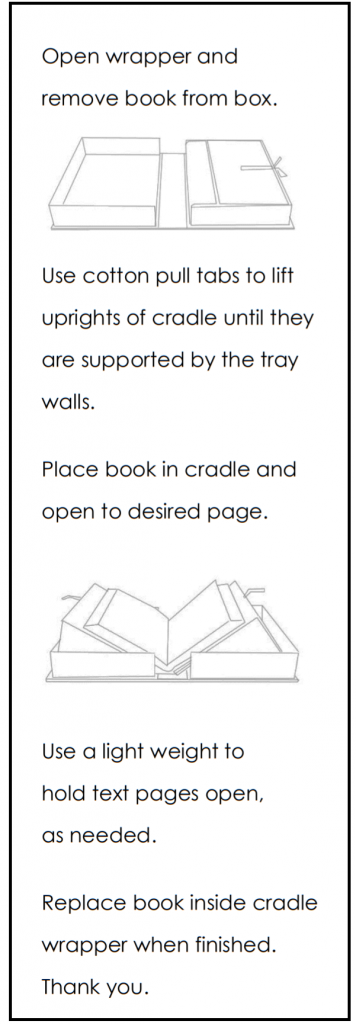

Next step was to attach coroplast backings and mounting hardware so we could screw them into place in the crates. It also gave us a chance at a closer look at the damage the frames have sustained over the years. Our decision to remove these now was confirmed when we saw that the eye screws in some were starting to pull out of the frames.

|

|

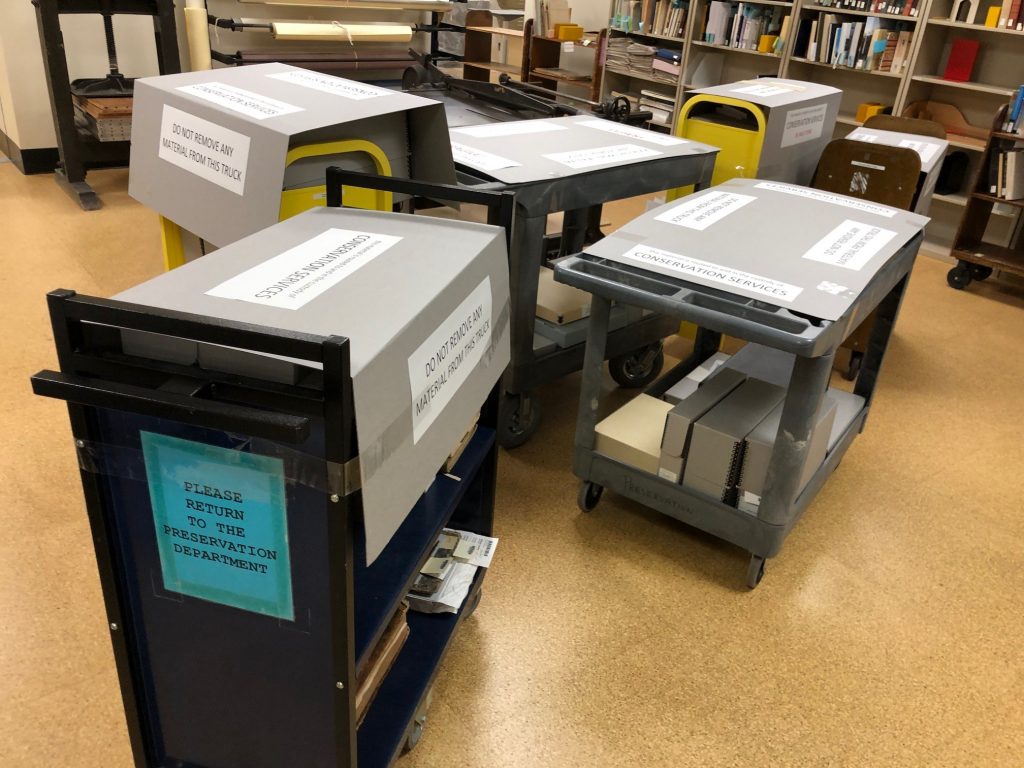

Next was to get them secured in the crates and labeled. We asked Cataloging to create stub records and assign barcodes for these so we could track their location in storage.

|

|

Once crated they were ready to move to the LSC. We had extra hands on site so that we could move them safely out of the building, down the ramp, and onto the truck. As four people moved the crates, one stayed with the truck to make sure the contents were secure.

|

|

|

|

These are now safely at LSC. One of the things we did right was to write the name of the portrait and the barcode on both ends of the crates just in case our lovely picture labels would not be visible when they were placed in the facility. Turns out that was a great idea because that is exactly what happened.

Moving these while the library closed proved to be a good decision. We had space to work safely and didn’t have to worry about working around staff or students.

The paintings will come back to Lilly Library eventually, once they’re able to be rehung safely and securely.

Photos courtesy Kelley Lawton, Rachel Penniman, and Beth Doyle.