Life at Trinity College During the Great War

By Mandy Cooper, Ph.D.

One hundred and one years ago, the doors to the East Duke Parlors were “thrown open” and “tables and machines [were] hauled in” along with “oilcloth, bleaching, hammer and tacks.” Led by Trinity College’s newly established branch of the Young Women’s Christian Association (YWCA), the women at Trinity College and in the surrounding community turned the East Duke Parlors into a Red Cross room.

According to Trinity’s YWCA president Lucile Litaker, the room was now “splendidly equipped” and “great bundles of material began to appear.” Throughout the next year, women at Trinity were joined by women from Durham to roll and send bandages overseas. The Red Cross room was officially open every Tuesday and Friday afternoon 2:00-4:30, with the Trinity Chronicle reporting in February 1918 that between forty and fifty women had worked in the room the previous Friday. The women at Trinity were determined to do their part for the war effort.

They were not the only ones. By the 1917–1918 school year, the United States had officially entered World War I, and Trinity was feeling its effects. The impact on enrollment was immediate. Trinity saw a decrease of over one hundred enrolled students during the 1916–1917 and 1918–1919 academic years. President William P. Few was alarmed and attempted to boost enrollment in multiple ways: he encouraged current students to remain at Trinity until they were drafted; he toured North Carolina to promote the need for college-educated men to rebuild a war-ravaged Europe; and, like many other North Carolina universities, he started a Student Army Training Corps (SATC) unit on campus. The young men who enrolled in the SATC officially joined the U.S. Army, but remained students at their institutions and were protected from the draft while receiving the training necessary to be considered for officer positions after graduation. Special classes were established for the SATC to ensure that those enrolled received the necessary training. The War Department required that Trinity create a course for the SATC that covered the “remote and immediate causes of the war and on the underlying conflict of points of view.” This course was intended to enhance the SATC’s morale and help them understand the “supreme importance to civilization” of the war.

Few’s worries that Trinity would lose many students “to government service of one kind or another” proved apt. Although Few tried to dissuade freshman Charlton Gaines from leaving Trinity when he heard of his plans, Gaines enlisted and was sent to Camp Meigs for training. He apologized to Few shortly after arriving at Camp Meigs for leaving “without giving you notice of my departure.” Gaines served throughout the war, attaining the rank of Sergeant in the Quartermaster Corps, and never returned to Trinity College.

Even those students who remained at Trinity felt the effects of the war. Friends and former students who had joined the military often returned to campus to visit on the weekends. The Chronicle reported in January 1918 that there would be no Chanticleer for the 1917–1918 year, largely because of the war. In addition to financial woes carried over from the previous year, the editor-elect had failed to return to Trinity in fall 1917—presumably because he joined the army. As the Chronicle writer reported, though, Trinity was not the only college (even just in North Carolina) that had been forced to cancel the yearbook for the year. In the end, the writer told students that they must “patriotically adapt” themselves to this situation because “since the war began ‘times ain’t what they used to be.’” The Chanticleer returned in 1919 as a special edition. It was issued at the end of the war, published as Victory, 1919, and highlighted the victory of the United States and its allies in the war.

The war had some unexpected effects on Trinity as well. Football had been banned at Trinity since 1895, and in 1918 students petitioned for its return. They argued that a football program would help build a manly physique during a time when there was “a distressing need for physically well-developed men.” As the war was ending, the administration lifted the ban and football returned to Trinity.

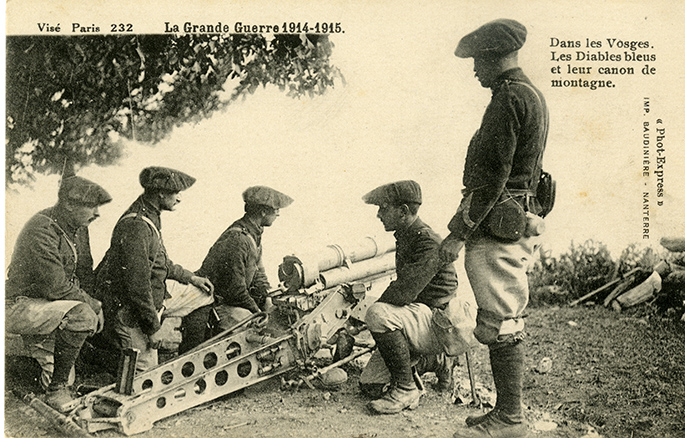

Trinity’s connection to the war was never more clear than in the masses of letters that alumni and former students sent to friends still at Trinity, to President Few or other faculty, to the Trinity Chronicle, or to the Alumni Register. Lt. R. H. Shelton wrote to Duke Treasurer D. W. Newsome from the front in France, telling him that he had seen “some of the worst over here.” Shelton continued, “Sherman certainly knew what he was talking about, but his was an infant.” Alumni like Shelton made the horrors of war clear to everyone still at Trinity. The pages of the Alumni Register for the war years are filled with letters from the front, placed in the same volumes as the President’s updates on the war’s effect on the college.

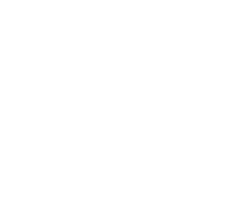

The Alumni Register and the Chronicle both regularly reported on the service of Trinity alumni and students overseas, including the first alumnus killed in action. First Lieutenant Robert “Kid” Anderson was among the first wave of American soldiers sent overseas. Part of the class of 1914, he was killed in action on May 29, 1918, at the Battle of Cantigny in France—the first major American engagement in the war. The news of Anderson’s death was sent both to his family and to President Few. The Alumni Register announced that Anderson had been killed in action in its July 1918 issue. The Register profiled his time at Trinity and his military service before reprinting an account of the memorial service held in his honor in his hometown of Wilson, North Carolina, a letter to Anderson’s parents from a fellow soldier that described his bravery in action, and portions of Anderson’s letters to relatives and friends.

To honor the centennial of the end of the First World War, selected items from the Duke University Libraries are on display in the Mary Duke Biddle Room as part of the exhibit Views of the Great War: Highlights from the Duke University Libraries. In addition to the impact of World War I on Trinity College and other people back home, the exhibit highlights aspects of the Great War and tells the personal stories of a few of the men and women (whether soldiers, doctors, or nurses) who travelled to France with the American Expeditionary Force during the “war to end all wars.” The exhibit is on display through February 2019.

Mandy Cooper is a Duke History Ph.D. and former Research Services Graduate Intern with the Rubenstein Library. She is one of the curators of the exhibit Views of the Great War.