Lead Gifts Support Planned Renovation and Expansion

By Aaron Welborn, Director of Communications

In December, President Vincent E. Price shared with the Duke community some tidings of comfort and joy. The Duke University Libraries had received $10 million, Price announced in a press release, in support of the planned renovation and expansion of Lilly Library, one of Duke’s oldest and most architecturally significant buildings.

The donation is comprised of three gifts: a $5 million grant from Lilly Endowment Inc., $2.5 million from Irene and William McCutchen and the Ruth Lilly Philanthropic Foundation, and $2.5 million from Virginia and Peter Nicholas.

Altogether, the gifts represent approximately one-fourth of the projected renovation cost. And they come from a family with a long association with Duke, and with Lilly Library in particular.

Lilly Library is named for Ruth Lilly, the famed philanthropist and last great-grandchild of pharmaceutical magnate Eli Lilly. In 1993, Lilly made a gift to “renovate and computerize” the library where her two nieces, sisters Irene “Renie” Lilly McCutchen and Virginia “Ginny” Lilly Nicholas, spent time as they attended the Woman’s College at Duke, graduating in 1962 and 1964, respectively. The gift renamed the building and provided the first significant upgrade to the stately Georgian edifice since it was built in 1927.

Renie and William McCutchen, a 1962 graduate of Duke’s Pratt School of Engineering, have a history of giving to Duke, primarily toward the Duke Divinity School.

Ginny and Peter Nicholas, a 1964 graduate of the Trinity College of Arts & Sciences, are also longtime donors to Duke, most notably for their naming gift for the Nicholas School of the Environment.

Among the members of the McCutchen and Nicholas families and their children, ten have attended Duke (one Nicholas grandchild is enrolled currently), and both families have a distinguished tradition of generosity and service to the university.

Lilly Endowment Inc. is an Indianapolis-based, private philanthropic foundation created in 1937 by three members of the Lilly family—J. K. Lilly Sr. and sons J. K. Jr. and Eli—through gifts of stock in their pharmaceutical business, Eli Lilly and Company. In keeping with the wishes of the three founders, Lilly Endowment exists to support the causes of religion, education, and community development. Throughout its history, the endowment has made grants totaling nearly $9.9 billion to almost ten thousand charitable organizations. At the end of 2017, the endowment’s assets totaled $11.7 billion.

“These remarkably generous gifts from the Nicholas and McCutchen families and the grant from Lilly Endowment will enable us to dramatically improve the academic experience for Duke students and faculty, while preserving the charm and character of Lilly’s most beloved spaces,” said Deborah Jakubs, the Rita DiGiallonardo Holloway University Librarian and Vice Provost for Library Affairs. “While Lilly Library and its staff are popular with first-year students and other library users, the lack of services and adequate space prevents it from fully meeting their needs. Many of the library services and spaces today’s students need to succeed are available in Perkins and Bostock Libraries on West Campus, but not yet on East.”

The planned renovation and expansion will update facility needs—including enhanced lighting, technology infrastructure, and furnishings—to meet today’s standards of safety, accessibility, usability, and service. Anticipated changes will also extend to the elegant Thomas, Few, and Carpenter reading rooms while maintaining the charm and character of these favorite spaces.

The proposed renovated building will also feature several new spaces for collaborative research and academic services, such as tutoring space for the Thompson Writing Program, event space for the Duke FOCUS Program, a student-testing facility, and an exhibit gallery. An anticipated added entrance and commons space holds promise to become the crossroads for East Campus that the von der Heyden Pavilion is for West, a place where students and faculty can meet over coffee.

“Our family’s commitment to restore and expand Duke’s library that bears the Lilly name comes from our hearts,” said Renie McCutchen and Ginny Nicholas. “We are happy to continue to support the same exceptional education and student experience as Duke has provided for three generations of the Lilly family.”

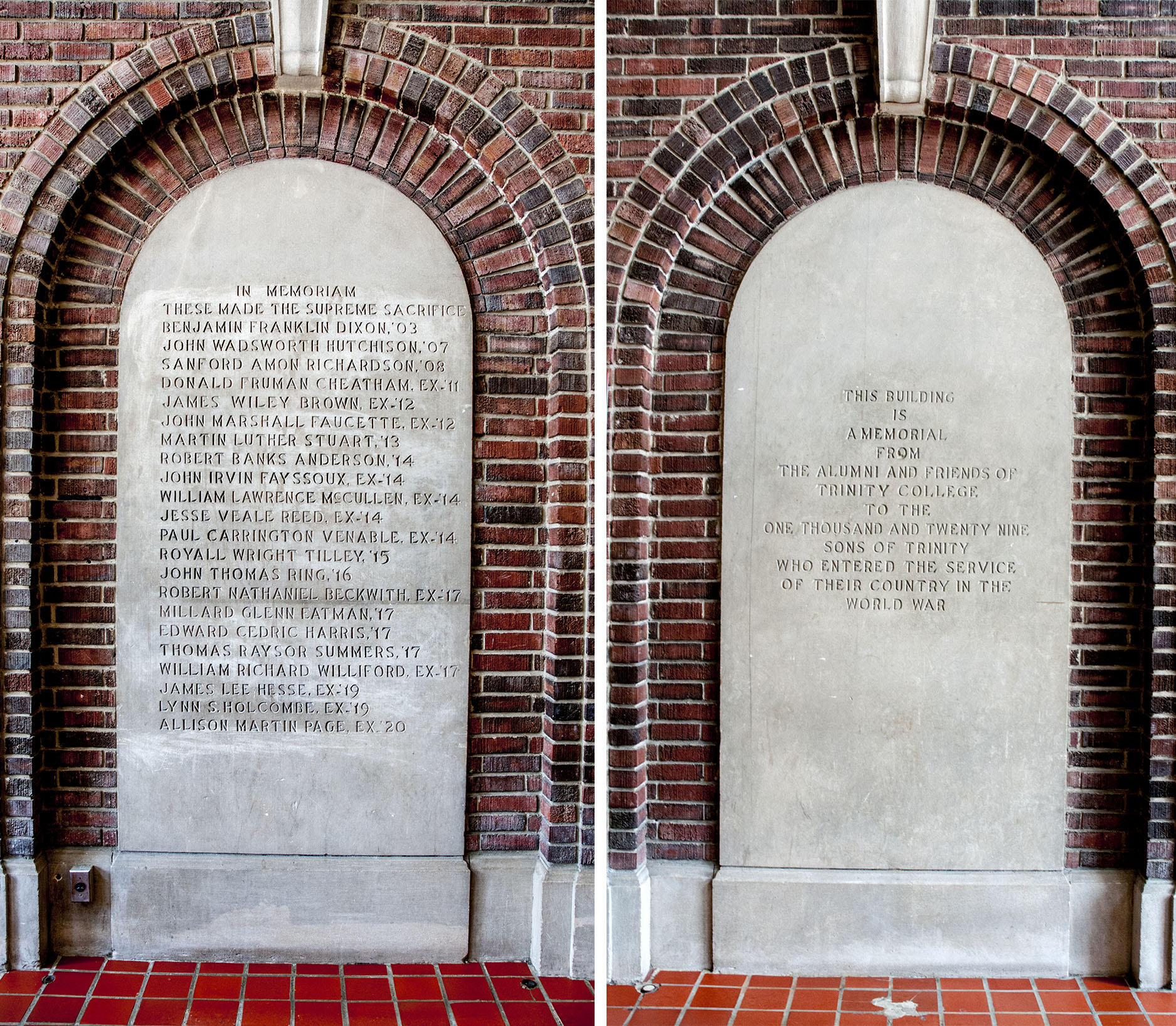

The building now known as Lilly Library opened in 1927 as Duke University’s first library on East Campus while West Campus was being constructed. At that time, it had a collection of around 100,000 books and was designed to serve a population of some 1,400 students. For more than four decades it served as the Woman’s College Library. When the Woman’s College merged with Trinity College of Arts & Sciences in 1972, the library was renamed the East Campus Library until 1993, when it was rededicated in honor of Ruth Lilly.

Over the course of that history, the very nature of libraries has also been redefined several times by technology, educational trends, and the demands of library users.

Today, more than 1,700 first-year Duke students make East Campus their home every year, and Lilly serves as their gateway to the full range of library collections and services. Faculty and graduate students whose departments are on East Campus also depend on Lilly for library services and materials, as does anyone who uses the art, art history, and philosophy collections housed there.

The total projected cost of the renovation and expansion is anticipated to be $38 million, which will largely be funded through philanthropy.

The Lilly family has been long been known for its support of libraries. In addition to Duke’s Lilly Library, there are Lilly libraries at Indiana University-Bloomington (with separate libraries named after Ruth Lilly at IU’s schools of law and medicine), Wabash College, Earlham College, and the Ruth Lilly Library at the Indianapolis Art Center.

As a Robertson Scholar, Hanna had the opportunity to spend one semester of her undergraduate years at UNC as a full-fledged Duke student. Though her time at Duke may have been limited, the impact it had on shaping her work was anything but. An African American Studies major, Hanna is interested in religious history in black communities both in America and globally. Her paper, “Seeking Canaan: Marcus Garvey and the African American and South African Search for Freedom,” was so good it had the rare distinction of winning both an Aptman Prize and a Middlesworth Award.

As a Robertson Scholar, Hanna had the opportunity to spend one semester of her undergraduate years at UNC as a full-fledged Duke student. Though her time at Duke may have been limited, the impact it had on shaping her work was anything but. An African American Studies major, Hanna is interested in religious history in black communities both in America and globally. Her paper, “Seeking Canaan: Marcus Garvey and the African American and South African Search for Freedom,” was so good it had the rare distinction of winning both an Aptman Prize and a Middlesworth Award. As a student, Gabi interned with the American Society of Papyrologists. As it happens, the ASP is headquartered at Duke, which is also home to countless papyrus materials in the Rubenstein Library. Gabi attributes the line of inquiry that inspired her paper—“Rostovtzeff and the Yale Diaspora: How Personalities and Communities Influenced the Development of North American Papyrology”—to her relationship with ASP and the ease to which she could access rare materials.

As a student, Gabi interned with the American Society of Papyrologists. As it happens, the ASP is headquartered at Duke, which is also home to countless papyrus materials in the Rubenstein Library. Gabi attributes the line of inquiry that inspired her paper—“Rostovtzeff and the Yale Diaspora: How Personalities and Communities Influenced the Development of North American Papyrology”—to her relationship with ASP and the ease to which she could access rare materials. As a student of Global Cultural Studies and founder of the Duke Men’s Project, Andrew was accustomed to exploring and interrogating narratives in his environment while at Duke. Choosing to spend his summer as one of the first participants in our Duke History Revisited program—a six-week immersive research experience uncovering previously under-researched or unexplored areas of Duke history—Andrew was able to delve deep into the relationship between Duke and Durham through the lens of housing and gentrification.

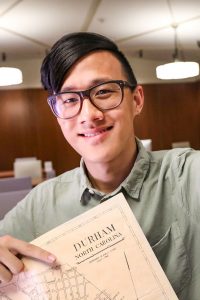

As a student of Global Cultural Studies and founder of the Duke Men’s Project, Andrew was accustomed to exploring and interrogating narratives in his environment while at Duke. Choosing to spend his summer as one of the first participants in our Duke History Revisited program—a six-week immersive research experience uncovering previously under-researched or unexplored areas of Duke history—Andrew was able to delve deep into the relationship between Duke and Durham through the lens of housing and gentrification. Alex’s creative writing piece, a series of vignettes titled “Reports from South Texas,” followed his interests and experiences. Inspired by his mother’s house in San Antonio, the piece reflects on the contradiction between sentimental memory and physical rot. In writing it, Alex found a way to hold onto a place that may be slipping away. He is grateful he didn’t have to undergo the process alone.

Alex’s creative writing piece, a series of vignettes titled “Reports from South Texas,” followed his interests and experiences. Inspired by his mother’s house in San Antonio, the piece reflects on the contradiction between sentimental memory and physical rot. In writing it, Alex found a way to hold onto a place that may be slipping away. He is grateful he didn’t have to undergo the process alone. Some might know Valerie as the President of Duke Players, the student theater group supporting new work from the Duke community, or as an actress in campus productions. However, behind the curtain, Valerie is often responsible for the writing herself. A junior, Valerie unites her studies in English, Creative Writing, and Theater Studies to create her very own plays and even see them to production.

Some might know Valerie as the President of Duke Players, the student theater group supporting new work from the Duke community, or as an actress in campus productions. However, behind the curtain, Valerie is often responsible for the writing herself. A junior, Valerie unites her studies in English, Creative Writing, and Theater Studies to create her very own plays and even see them to production.