Writer’s Page

by Robert J. Bliwise

This summer was contest time at The New York Times. The venerable (and, if circulation patterns hold, vulnerable) paper invited students to respond to Rick Perlstein’s, “What’s the Matter With College?” Author and historian Perlstein argues that college, as a discrete experience, has begun to disappear. In the late 1960s, college was a cultural obsession because, well, it was so countercultural.  No longer: The campus has become conventional, lured by the imperatives of entertainment, consumed by the values of marketing, and dedicated to producing investment bankers. “Just as the distance between the campus and the market has shrunk,” he writes, “so has the gap between childhood and college—and between college and the ‘Real World’ that follows.”

No longer: The campus has become conventional, lured by the imperatives of entertainment, consumed by the values of marketing, and dedicated to producing investment bankers. “Just as the distance between the campus and the market has shrunk,” he writes, “so has the gap between childhood and college—and between college and the ‘Real World’ that follows.”

Perlstein arrived at his conclusions after immersing himself in student conversations at the University of Chicago, which, twenty years ago, produced a scholar who pronounced an even harsher verdict on higher education. That was Allan Bloom, with The Closing of the American Mind. (The book’s pointed if somewhat ponderous subtitle is “How Higher Education Has Failed Democracy and Impoverished the Souls of Today’s Students.”) Bloom was a professor of philosophy and political science at Chicago; he was a translator and editor of Plato’s Republic and Rousseau’s Emile, both classic education tracts. Earlier in his career, he had taught at Cornell University—this during a time of student protests and building takeovers, unsettling episodes that he revisited in the book.

The Closing of the American Mind was a surprising sensation in the marketplace. A review in The New York Times hailed it as “essential reading for anyone concerned with the state of liberal education in this society.” Duke religion professor Kalman Bland observes that at the time the book appeared, at the height of the Reagan presidency, “bashing liberalism was fashionable. It also didn’t hurt sales that Saul Bellow’s prestigious name adorned the dust cover, announcing his foreword. It also didn’t hurt that Bloom gave voice to stodgy elders who were dismayed at the younger generation’s tastes in music and popular culture. A good inter-generational scold sells books, I suppose.”

Bloom himself, interviewed in The Chronicle of Higher Education, claimed he was “astonished” by “the favorableness of the response.” He added, “I thought my students and my small circle would have some interest in it…. Obviously, this was the right moment.”

Right moment or not, most readers, it’s easy to surmise, skipped over the lengthy discourse on European philosophical movements (with chapter headings like “The German Connection”). They were drawn, instead, to the opening section on students; there, the chapter on “Relationships” was divided into topics like “Self-Centeredness,” “Race,” and “Eros.”

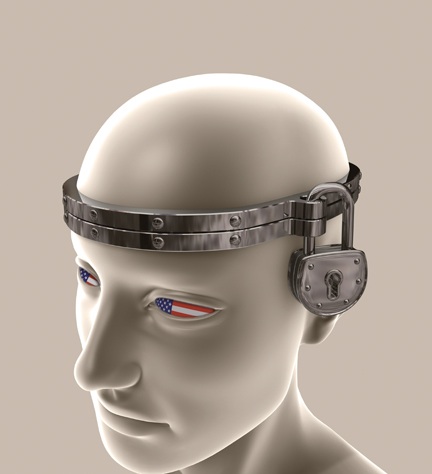

Bloom conceived the book as “a meditation on the state of our souls, particularly those of the young, and their education.” He lamented what he saw as the decay of the humanities and the turning away from intellectual engagement—or from virtue—that resulted. “Today’s select students know so much less, are so much more cut off from the tradition, are so much slacker intellectually, that they make their predecessors look like prodigies of culture,” he wrote. Students arrive on campus “ignorant and cynical” about their political heritage, dispossessed of “respect for the Sacred,” and indifferent to the power of books as transmitters of tradition.

In Bloom’s view, youth culture—as expressed in its essence through the rawest of rock music—has drowned out any countervailing nourishment for the spirit. Young people have been conditioned, as it were, to see everything as conditional, or relative, whether the quality of books or the quality of relationships.

As Duke political scientist Michael Gillespie notes, the book was pounced upon by parents who saw their worst fears confirmed—that their children were out of control and that values-depleted campus environments would only foster more of the same. Gillespie taught at the University of Chicago and knew Bloom there. His older colleague, he observes, wasn’t convinced that democracy was good for breeding culture in young people (not that any other political system would be any better). As a scholar of Plato, Bloom was attuned to other transmission mechanisms. He wanted to channel erotic longing, which Plato identifies as a basic human impulse, into a longing for higher things. But as The Closing of the American Mind argued, the American campus had neglected that imperative as it abandoned the high-minded European intellectual tradition.

A sign of such abandonment, Bloom asserted, was a curriculum devoid of meaning, one that shied away from asking the questions that would elevate moral life. He said the humanities, in particular, suffer from “democratic society’s lack of respect for tradition and its emphasis on utility.”

Two years ago, The Chronicle of Higher Education looked at what has become a constant of the curriculum, literary theory. The article noted that theory has become entrenched in “the literary profession,” but that there’s no clear notion of what it means to be asking theoretical questions of a work of literature. One professor described the field as a free-for-all. “Theory has no material coherence, only an attitude,” he noted. Another professor was quoted as declaring that students “don’t have a background in literature because that isn’t anything that anyone thinks is of value anymore.” One can imagine the depths of Bloomian despair over such illustrations of intellectual fragmentation.

Just after the book was published, Duke Magazine brought together professors to ponder The Closing of the American Mind; the conversation was later edited for publication. Twenty years ago, in the faculty roundtable, Kalman Bland had this to say about Bloom: “He sees the university as an institution in society, and the function of the university in society as going against the grain. That’s the good part of the book—showing that the university does fit into the social context, and that it defines itself in relationship to the needs and values of that context. And the book asks us to take a close look at whether or not we’re serving the powers that be or whether we’re being the gadflies—the Socratic model of shaking our students up and liberating them from their popular biases.”

And what of the relationship now between campus culture and the wider culture? One answer comes in Louis Menand’s “Talk of the Town” essay in the May 21, 2007, issue of The New Yorker. Menand reported that the biggest undergraduate major by far today is business. Twenty-two percent of bachelor’s degrees are awarded in the field; less than four percent of college graduates major in English, and only two percent in history.

Looking at Duke today, Bloom might feel at once perplexed and vindicated, says Kalman Bland. From Registrar’s Office figures, Bland has found that the cohort of Duke students majoring and minoring in economics (648) exceeds the students majoring and minoring in philosophy(117) by almost 600 percent. “Perhaps, like many of us, Bloom would lament the practical pre-professionalism of so many of our students,” Bland says, and “be appalled at the miniscule number of majors and minors” in the traditional humanities. That relatively small numbers of students have chosen to major or minor in women’s studies or African and African American studies “would surely warm the cockles of his old-worldly, anti-liberal, anti-democratic, elitist, metaphysically-inclined, conservative heart.” (Bloom’s “vehement anti-feminism” had made “sexist patriarchy sound respectable,” Bland says.)

Bloom’s conservative heart helped shape a sort of literary genre, the higher-education critique. The Closing of the American Mind begat Charles Sykes’ 1988 Profscam: Professors and the Demise of Higher Education, which begat Roger Kimball’s 1990 Tenured Radicals: How Politics Has Corrupted Higher Education, which begat David Horowitz’s recent The Professors: The 101 Most Dangerous Academics. The genre is populated by screeds against professors and their presumed political agendas; Bloom had a wider focus, as does Perlstein, in his recent essay.

“If Perlstein wants a return to the ideals of an academy that is critical of the values of the larger society, the Bloom tradition aims at an embrace of traditional standards and norms,” says classical-studies professor Peter Burian, another participant in the original Duke Magazine conversation. “For Bloom, it was an issue that students were being assigned Toni Morrison rather than Plato, for Perlstein, that students mostly ignore both and the issues they raise.” Of course, if Perlstein’s lament rings true that college has lost its critical distance, then the so-called tenured radicals—concentrated as they are in the humanities—are marginalized. As Burian puts it, faculty members in areas like economics, business, engineering, and the sciences “have no problem with the disappearance of any distance—in terms of research funding and agendas and subjects taught—from the claims of the real world and its markets.”

Though it hardly had the marketplace success of The Closing of the American Mind, one book this summer aspired to a similar status as cultural critique. That was The Cult of the Amateur, by Andrew Keen, a Silicon Valley entrepreneur and writer. Considering such phenomena as Wikipedia, the blogosphere, and YouTube, Keen argues that the Web is threatening the very future of our cultural institutions. It’s all part of “the great seduction,” as he labels it—perhaps (or perhaps not) with a nod to Plato. The “revolution” unleashed by the Web, he writes, “has peddled the promise of bringing more truth to more people—more depth of information, more global perspective, more unbiased opinion from dispassionate observers.” In his view, this is all a smokescreen. What the revolution is really delivering is “superficial observations of the world around us rather than deep analysis, shrill opinion rather than considered judgment.”

For someone who decries a culture of shrillness, Keen can seem awfully shrill. But in a sense he’s illustrating the latest expression of what Bloom called democratic relativism. Twenty years after The Closing of the American Mind, we have cause to wonder if a culture with multiple seductions—real and virtual alike—can find an effective counterforce in the college experience.

Robert J. Bliwise is editor of Duke Magazine and an adjunct instructor in magazine journalism at Duke’s Terry Sanford Institute.

Robert J. Bliwise is editor of Duke Magazine and an adjunct instructor in magazine journalism at Duke’s Terry Sanford Institute.

Get more about the college experience

Michael Bérubé. What’s Liberal About the Liberal Arts? New York: W.W. Norton, 2006.

Allan Bloom. The Closing of the American Mind. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1987.

Derek Bok. Our Underachieving Colleges. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2006.

Rachel Donadio. “Revisiting the Canon Wars.” The New York Times Book Review, Sept. 16, 2007.

Darryl J. Gless and Barbara Herrnstein Smith (eds.). The Politics of Liberal Education. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1992.

Lawrence W. Levine. The Opening of the American Mind. Boston: Beacon Press, 1996.

Anne Matthews. Bright College Years. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1997.

Bill Readings. The University in Ruins. Boston: Harvard University Press, 1996.

Henry Rosovsky. The University: An Owner’s Manual. New York: W.W. Norton, 1990.

Charles J. Sykes. ProfScam. Washington, D.C.: Regnery Gateway, 1988.

Hi, Neat post. There is a problem with your site in internet explorer, would test this… IE still is the market leader and a large portion of people will miss your excellent writing because of this problem.