This is the seventh in a series of blog posts on global pandemics written by the staff of Duke Libraries’ International and Area Studies Department. Like the first, second, third, fourth, fifth, and sixth posts, it is edited by Ernest Zitser, Ph.D., Librarian for Slavic, Eurasian, and East European Studies, library liaison to the International Comparative Studies Program, and Adjunct Assistant Professor in the Department of Slavic and Eurasian Studies at Duke University. The following post is written by Heidi Madden, Ph.D. , Librarian for Western European and Medieval Renaissance Studies.

This is the seventh in a series of blog posts on global pandemics written by the staff of Duke Libraries’ International and Area Studies Department. Like the first, second, third, fourth, fifth, and sixth posts, it is edited by Ernest Zitser, Ph.D., Librarian for Slavic, Eurasian, and East European Studies, library liaison to the International Comparative Studies Program, and Adjunct Assistant Professor in the Department of Slavic and Eurasian Studies at Duke University. The following post is written by Heidi Madden, Ph.D. , Librarian for Western European and Medieval Renaissance Studies.

Most of the pandemic reading lists that you will find online, such as the ones mentioned in my previous blog post, tend to feature modern or contemporary English language publications and (with very few exceptions, such as Boccaccio’s Decameron) to focus almost exclusively on Anglo-American literature. In this blog post, I want to highlight plague narratives of continental Europe and to present three pre-modern works from France, Italy, and German-speaking lands, which are beloved in their countries of origins, but are, for one reason or another, not as well-known abroad.

The Fables of Jean de la Fontaine

One of the ways pre-modern authors dealt with the Plague was to turn it into an allegory and use it for didactic ends. That is precisely what Jean de La Fontaine (1621–1695) did when he composed a fable, in free verse, entitled “Animals Sick of the Plague” (Les Animaux malades de la peste), one of the required plague texts of early modern France. This fable was one of the 239 published between 1668 and 1694, in 12 books of Fables, a publication that turned this French fabulist into one of the most widely read poets of the seventeenth century and a model for other writers throughout Europe. Although La Fontaine’s fables were originally dedicated to the heir-to-the-throne (who was just 7 years old in 1668), they were by no means intended to serve merely as entertaining children’s literature (as they have come to be used today). La Fontaine culled his stories from both classical (Greek and Roman) fabulists and their “Oriental” (Persian, Indian, etc.) counterparts (at least those available in French or Latin translation). He then transformed them into memorable verses and infused them with the wit and wisdom for which he has become justly famous. Indeed, to this day, you cannot truly be French if you are not able to recite from memory a poem by La Fontaine or quickly understand an aphoristic colloquialism that derives from his Fables.

One of the ways pre-modern authors dealt with the Plague was to turn it into an allegory and use it for didactic ends. That is precisely what Jean de La Fontaine (1621–1695) did when he composed a fable, in free verse, entitled “Animals Sick of the Plague” (Les Animaux malades de la peste), one of the required plague texts of early modern France. This fable was one of the 239 published between 1668 and 1694, in 12 books of Fables, a publication that turned this French fabulist into one of the most widely read poets of the seventeenth century and a model for other writers throughout Europe. Although La Fontaine’s fables were originally dedicated to the heir-to-the-throne (who was just 7 years old in 1668), they were by no means intended to serve merely as entertaining children’s literature (as they have come to be used today). La Fontaine culled his stories from both classical (Greek and Roman) fabulists and their “Oriental” (Persian, Indian, etc.) counterparts (at least those available in French or Latin translation). He then transformed them into memorable verses and infused them with the wit and wisdom for which he has become justly famous. Indeed, to this day, you cannot truly be French if you are not able to recite from memory a poem by La Fontaine or quickly understand an aphoristic colloquialism that derives from his Fables.

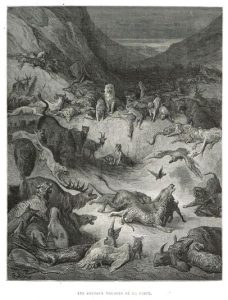

“Animals sick of the plague” (Fable CXXV) tells the story about a time when almost all the animals in the world had died from a terrible infectious disease. The Lion, king of the animals, declares that the plague was sent by the gods as a punishment for everyone’s sins. He decides that each of the surviving animals should publicly confess their sins and that the animal whose sin is the gravest should be sacrificed to atone on behalf of everyone else. The Lion confesses to killing innocent Sheep (and even the shepherd who tended them). When it is the Fox’s turn to confess, he succeeds in talking the Lion out of his guilt by describing the Sheep as inferior beings, who deserved nothing better. The other animals follow the Fox’s example and insist that they have committed no sins. Only the Donkey follows the Lion’s instructions to the letter and admits that he ate some delicious grass from someone’s property without permission. Since he was the only one to plead guilty, the animals condemn the Donkey to death. The moral of the story is: “If you are powerful, wrong or right, / The court will change your black to white.”

This fable, with animals as stock characters, devoid of any identifiable social situation, and therefore universally true, speaks to us even after 400 years. “Animals Sick of the Plague” addresses the age-old question: should political leaders surround themselves with yes-men, sycophants, and toadies or should they pick people whose moral character and commitment to truth trumps their loyalty to a single individual, political party, or special interest? Although this poem merely references the plague, without describing the outbreak in any detail, the infectious disease serves as the litmus test for the king and his court. La Fontaine’s ironic moral suggests that although this ruler and his cronies seem to succeed politically, they fail the real test of leadership that a pandemic demands from the holders of public office. While the poet’s use of the words “black” and “white” reference a problematic and longstanding association of guilt and innocence with color, the French cartoon (above) represents a modern interpretation that makes this fable seem even more relevant, especially at a time when contemporary social movements seek to address the systemic inequalities — legal, socio-economic, racial — exposed by the COVID-19 pandemic.

This fable, with animals as stock characters, devoid of any identifiable social situation, and therefore universally true, speaks to us even after 400 years. “Animals Sick of the Plague” addresses the age-old question: should political leaders surround themselves with yes-men, sycophants, and toadies or should they pick people whose moral character and commitment to truth trumps their loyalty to a single individual, political party, or special interest? Although this poem merely references the plague, without describing the outbreak in any detail, the infectious disease serves as the litmus test for the king and his court. La Fontaine’s ironic moral suggests that although this ruler and his cronies seem to succeed politically, they fail the real test of leadership that a pandemic demands from the holders of public office. While the poet’s use of the words “black” and “white” reference a problematic and longstanding association of guilt and innocence with color, the French cartoon (above) represents a modern interpretation that makes this fable seem even more relevant, especially at a time when contemporary social movements seek to address the systemic inequalities — legal, socio-economic, racial — exposed by the COVID-19 pandemic.

The Betrothed of Alessandro Manzoni

The plague of 1629–1631, which killed 25% of the Italian population, serves as the backdrop of a historical romance called The Betrothed (I promesi sposi), one of the most popular Italian novels ever published and, today, one of the lesser- known bestsellers of the nineteenth century. Originally published in three volumes between 1825 and 1827, the novel was the product of the pen of Alessandro Manzoni (1785–1873), a popular poet, novelist, and philosopher who was one of the cultural icons of the Italian nationalist revival movement (It. Risorgimento). The book was deliberately written in a clear, expressive prose style meant to be accessible to the broadest possible number of his fellow countrymen, which may explain not only Manzoni’s mass appeal during his lifetime, but also the reason why his prose became a model for many subsequent Italian authors.

The plague of 1629–1631, which killed 25% of the Italian population, serves as the backdrop of a historical romance called The Betrothed (I promesi sposi), one of the most popular Italian novels ever published and, today, one of the lesser- known bestsellers of the nineteenth century. Originally published in three volumes between 1825 and 1827, the novel was the product of the pen of Alessandro Manzoni (1785–1873), a popular poet, novelist, and philosopher who was one of the cultural icons of the Italian nationalist revival movement (It. Risorgimento). The book was deliberately written in a clear, expressive prose style meant to be accessible to the broadest possible number of his fellow countrymen, which may explain not only Manzoni’s mass appeal during his lifetime, but also the reason why his prose became a model for many subsequent Italian authors.

Like the works of his European contemporaries, Sir Walter Scott and Alexandre Dumas, Manzoni wrote novels firmly set in the turbulent history of the country that the author proudly claimed as his native land. The Betrothed is set in Northern Italy during the Thirty Years War (1618-1648) and combines keen descriptions of characters, social class, and landscapes with a humorous, swashbuckling tone reminiscent of The Three Musketeers or Ivanhoe. The plot is as convoluted as it is predictable: two main characters, Renzo and Lucia, are engaged and are about to be married by the local priest. The priest, however, has been threatened by professional thugs, who work for a local lord; they prevent the priest from performing the wedding ceremony because the local lord has made a bet that he can seduce Lucia. The young peasant couple flees the village and the reader follows the pair of lovers through almost three years of war, social upheaval, and an outbreak of the plague in the city of Milan. In the end, their unshakeable faith in God and their devotion to each other conquers all earthly obstacles and the novel closes with their marriage.

While this happy ending may have been a traditional way to end a novel, Manzoni’s work cleverly flipped the perspective of the typical plague narrative: here the society is narrated as a society exposed by the virus, not to the virus. Some details of the inadequate response to the outbreak sound particularly familiar: the governor of Milan does not cancel the birthday celebration for the prince, and thus, creates a super-spreader event. Even more poignant is Manzoni’s treatment of the role of rumors in the identification and targeting of scapegoats. In the revised, final version of the novel, published in 1842, the author even went so far as to add an appendix about “The History of the Column of Infamy” (Storia della colonna infame). This was a historical account of the infamous miscarriage of justice that occurred during the 1630 plague in Milan, when rumors about “spreaders” of the disease lead to the arrest, torture, and trial of several innocent men; a historical wrong that demonstrated, Manzoni argued, the inadequacy of the country’s judicial system. One cannot read this appendix today without thinking of the way COVID-19 has exposed the (dis)function of our legal system.

The Black Spider of Jeremias Gotthelf

Say “Black Spider” to any contemporary German speaker, and they will vividly recall the first time they read The Black Spider (Die schwarze Spinne) by Jeremias Gotthelf, early modern Germany’s answer to Steven King or Edgar Alan Poe. Gotthelf was actually the pen name of Albert Bitzius (1797–1854), a Swiss pastor who employed his considerable gifts as a writer to communicate his reformist concerns in the field of education and with regard to the plight of the poor. The Black Spider, which has recently been translated anew into English, is perhaps the most famous example of the way this highly didactic author used fear as an educational tool.

Say “Black Spider” to any contemporary German speaker, and they will vividly recall the first time they read The Black Spider (Die schwarze Spinne) by Jeremias Gotthelf, early modern Germany’s answer to Steven King or Edgar Alan Poe. Gotthelf was actually the pen name of Albert Bitzius (1797–1854), a Swiss pastor who employed his considerable gifts as a writer to communicate his reformist concerns in the field of education and with regard to the plight of the poor. The Black Spider, which has recently been translated anew into English, is perhaps the most famous example of the way this highly didactic author used fear as an educational tool.

A brief synopsis of the plot cannot do justice to the atmosphere of fear and horror that Gotthelf manages to create in the course of his novella. The story within a story deals with a contemporary storyteller spinning a yarn about an abusive medieval knight-landlord who overtaxes his serfs to such an extent that they are forced to turn for help to the Devil. A peasant girl named Christina, who serves as the village’s midwife, agrees to make a pact with the Beast, who disguises himself as a travelling huntsman. The pact is sealed with a kiss on the cheek. The kiss leaves a black mark that eventually takes on the shape of a black spider. At a certain point this spider rises up on Christina’s cheek and gives birth to a swarm of creepy-crawlies that hurry from her face, over her body, and toward the town. The swarm of spiders kills cattle and people alike; villagers sacrifice their lives to trap the black spider who gave birth to the swarm behind a black post of a window frame, but then the next generation once again, ignorantly and carelessly, unleashes the plague of spiders. Vivid images of horror upon horror make the listeners of the tale shiver in fear. And just when the contemporary audience thinks that the end of the story signals the end of the plague narrative to which they have been listening, they realize that the dreaded black spider of the tale-within-the-tale has been trapped in the old black post in the window frame of the very same house in which they are staying and is there, among them, at this very moment.

For all its drama and horror, Gotthelf’s novella raises themes that continue to resonate today. Among these is the reminder that the continued exploitation of the poor and marginalized members of society is a danger to everyone’s well-being; and that neither hubris nor reckless ignorance are the right attitudes for confronting recurrent public health problems like global pandemics. Sensible advice that could have real world applications.

So in what way are pre-modern literary treatments of pandemics, like the three Continental ones analyzed above, different from modern ones? In the centuries leading up to the modern plague novel, literary authors stopped narrating the plague historically and turned the medical plague into a metaphor for the plague as a social and psychological phenomenon. However, I find that pre-modern literature narrates fear and anxiety in a much more palpable way than modern plague novels, because they narrate fear at a time when medicine did not claim to have all the answers. That used to be a foreign concept to me. Until recently, I, like everyone else, thought that a pandemic could never happen to us, moderns, and that pandemics belonged to the past. In reading pre-modern plague stories, I find that the raw emotions expressed speak to me; they help me deal with this feeling of endlessly waiting for isolation to end and for a vaccine to be found.