One of the first lines of defense for a damaged book is a well-fitting enclosure. It can prevent loss of any loose pieces or additional strain on weaker binding materials from handling during shelving. Many of the books in special collections were boxed long ago or before their acquisition. When those items come into the lab for treatment, we evaluate the box for fit, function, and artifactual value to determine if it should be retained or replaced.

Lately I’ve been working on a 1545 edition of The Byrth of Mankynde from the Josiah Charles Trent History of Medicine collection. Originally published in 1540, this book is the oldest manual for midwifery printed in English. It contains several copper plate engravings of anatomy – apparently some of the first in England to be produced by roller press. My favorites are the figures of fetuses in utero, which look more like babies floating in light bulbs or balloons.

The book had been boxed decades ago in a very nice quarter-leather slipcase, with a shaped spine and false raised bands to make it look like a binding when sitting on the shelf. The maroon goatskin has been tooled in gold to mark the title, author, and publication information on the spine and along the “boards” where the leather meets the red cloth.

Slipcases can be damaging to a book if they fit too tightly, often causing abrasion on the boards as the book slides in and out. This slipcase avoids those problems with a 4-flap enclosure, which can be removed with a red ribbon pull tab on the fore-edge. Unfortunately that ribbon has started to split and is barely hanging on at this point.

Slipcases can be damaging to a book if they fit too tightly, often causing abrasion on the boards as the book slides in and out. This slipcase avoids those problems with a 4-flap enclosure, which can be removed with a red ribbon pull tab on the fore-edge. Unfortunately that ribbon has started to split and is barely hanging on at this point.

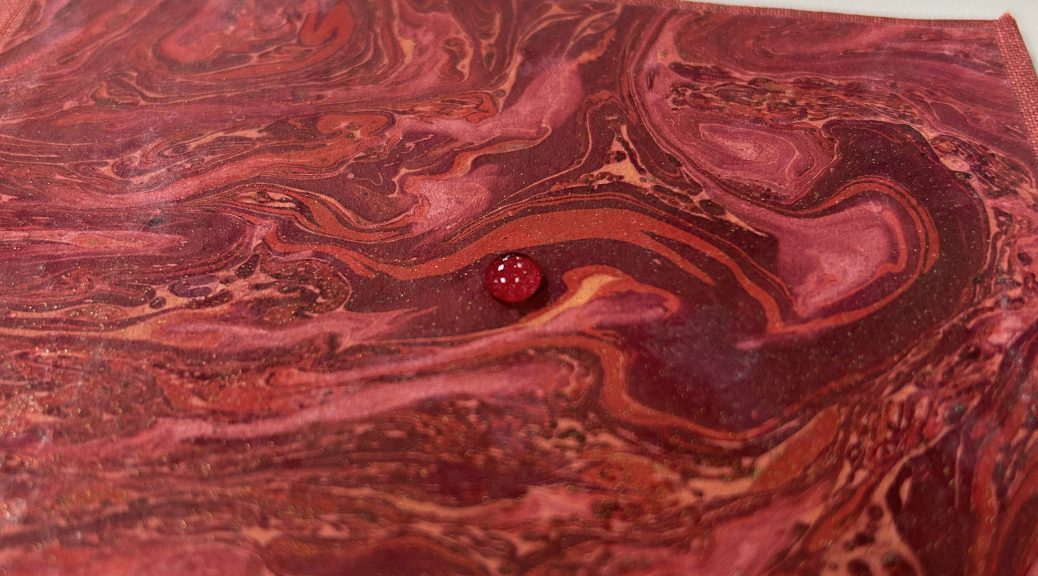

The inside of the 4-flap is covered with a red marbled paper that matches the colors of the other materials very well. It even includes small metallic flakes that sparkle a little as you open the box.

The inside of the 4-flap is covered with a red marbled paper that matches the colors of the other materials very well. It even includes small metallic flakes that sparkle a little as you open the box.

The interior of the slipcase is covered with the same marbled paper.

The interior of the slipcase is covered with the same marbled paper.

While these decorative papers really enhance the visual appeal of the box, they can present a number of problems for the book itself. Often the dyes or pigments used in colored papers can rub off onto a book through normal handling; if the binding material is lighter in color you might see some staining on the board edges.

While these decorative papers really enhance the visual appeal of the box, they can present a number of problems for the book itself. Often the dyes or pigments used in colored papers can rub off onto a book through normal handling; if the binding material is lighter in color you might see some staining on the board edges.

The bigger risk from these colored materials, though, is if the box ever gets wet. Much like a red sock in a load of white laundry, water-soluble dyes can easily transfer to the pages of the book and cause staining that may be impossible to remove. I worried that in a water event this box could turn all those little lightbulb babies bright pink.

An easy way to test for solubility is with a basic water drop test. Immediately after placing a very small drop of water onto the surface of the marbled paper, I used a piece of clean blotter to wick it up. Looking at the scrap of blotter, you can see if there was any discoloration or transfer of the solubilized media. You can repeat this process a couple of times with larger drops, left for a longer duration.

An easy way to test for solubility is with a basic water drop test. Immediately after placing a very small drop of water onto the surface of the marbled paper, I used a piece of clean blotter to wick it up. Looking at the scrap of blotter, you can see if there was any discoloration or transfer of the solubilized media. You can repeat this process a couple of times with larger drops, left for a longer duration.

I could see some transfer of red to the blotter when the water was in contact with the marbled paper for only a few seconds. The same test on the cloth produced a far more dramatic result.

I could see some transfer of red to the blotter when the water was in contact with the marbled paper for only a few seconds. The same test on the cloth produced a far more dramatic result.

I appreciate the quality of craftsmanship that went into making this enclosure. A lot of effort was put into making a very deluxe box for this significant and valuable book. The leather is pared well and the titling is very clean. The maker clearly spent time selecting leather, cloth, and marbled paper that went together. Unfortunately all those fancy materials present too much of a risk to the book and will need to be replaced. While the cloth-covered boxes that we make are pretty visually plain, that’s actually one of their strengths. The lack of decoration or color is often the safer choice… and you don’t want your box to outshine the book anyway.

I appreciate the quality of craftsmanship that went into making this enclosure. A lot of effort was put into making a very deluxe box for this significant and valuable book. The leather is pared well and the titling is very clean. The maker clearly spent time selecting leather, cloth, and marbled paper that went together. Unfortunately all those fancy materials present too much of a risk to the book and will need to be replaced. While the cloth-covered boxes that we make are pretty visually plain, that’s actually one of their strengths. The lack of decoration or color is often the safer choice… and you don’t want your box to outshine the book anyway.