By Aaron Welborn

The last few years have seen the blossoming of a vibrant arts scene at Duke. From major exhibitions at the Nasher Museum of Art to a new experimental and documentary arts MFA program, the arts have been taking center-stage on campus, and the university is investing more than ever in making them an integral part of the Duke experience.

The same trend can be seen here in the Libraries, where we hosted our first visiting artist-in-residence this year and witnessed the development of two original works of art inspired by archival collections. This is a different side of the library than most people normally see or think about—not the sanctuary of quiet study and serious scholarly work, but the “maker-space” of raw source material and artistic incubation.

“The greatest part of a writer’s time is spent in reading, in order to write,” said the great Samuel Johnson. “A man will turn over half a library to make one book.” He might have said the same about making one piece of music, or one play, or any other work of art. Creativity needs something to play with. And for many artists, no matter the media in which they work, the library is an open studio.

Here’s a look at three recent projects at Duke that celebrate the fruitful intersection of art and archives.

So Many Ways To Do Research

Steve Roden is a visual and sound artist based in Pasadena, California. His work includes painting, drawing, sculpture, film, video, sound installations, text, and performance pieces. Roden has shown and performed his work around the world, and his pieces are included in the permanent collections of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, the Museum of Contemporary Art in San Diego, and the National Museum of Contemporary Art in Athens, Greece, among other places.

This October, Roden spent three weeks at Duke as the inaugural Barbaralee Diamonstein-Spielvogel Visiting Artist. Named in honor of Dr. Diamonstein-Spielvogel, a prolific author, interviewer, and champion of the arts, this new biennial artist-in-residence program provides an extended opportunity for an artist to study and engage with collections in the David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library. The fellowship is open to artists working in all media, and fellows are given free rein to explore more than twenty centuries worth of history and culture represented in the collections of the Rubenstein Library.

During his first week on campus, Roden was treated to a parade of treasures from the Rubenstein Library’s holdings. A team of curators assembled selections of their favorite rare books, documents, and artifacts, ranging from ancient papyri and medieval medical treatises to the records of twentieth-century human rights organizations.

“It was like having dessert for every meal,” said Roden, who was a bit overwhelmed by the possibilities.

“Ever since I was young, I tended to like things older than me,” he said. “I have a fondness for old paper and things that decay.” Some of the archival materials brought out for Roden to investigate were related to things he collects on his own, like old photographs and sound recordings. Others took him by surprise, like the haunting illustrations from a sixteenth-century work on eye surgery.

This was not the first time Roden had gone fishing for ideas in archival waters. In 2011, he traveled to Berlin for a month-long residency at the Akademie der Künste, where he had been invited to work with the papers of the literary critic, philosopher, and translator Walter Benjamin. It was an unusual assignment, since Roden neither speaks nor reads German. Instead, he turned his eye toward the visual elements of Benjamin’s papers. The result was a series of works in multiple formats, entitled Ragpicker, inspired by the color-coded symbols Benjamin used to organize and annotate his work. Selections from Ragpicker were featured in solo exhibitions last year in New York and Los Angeles.

During his residency at Duke, Roden gave a public talk about the experience of working with Benjamin’s papers and how they had inspired a body of creative work. The rest of his time he spent working in the Rubenstein Library reading room, taking notes, making sketches, consulting different sources, meeting with students and faculty, and letting his curiosity guide him. “There are so many different ways you can do research,” he said.

It’s too early to say what Roden’s brand of research will unearth. But we look forward to inviting him back to show us what he discovered in the archives that we didn’t know was there.

A Present Part of History

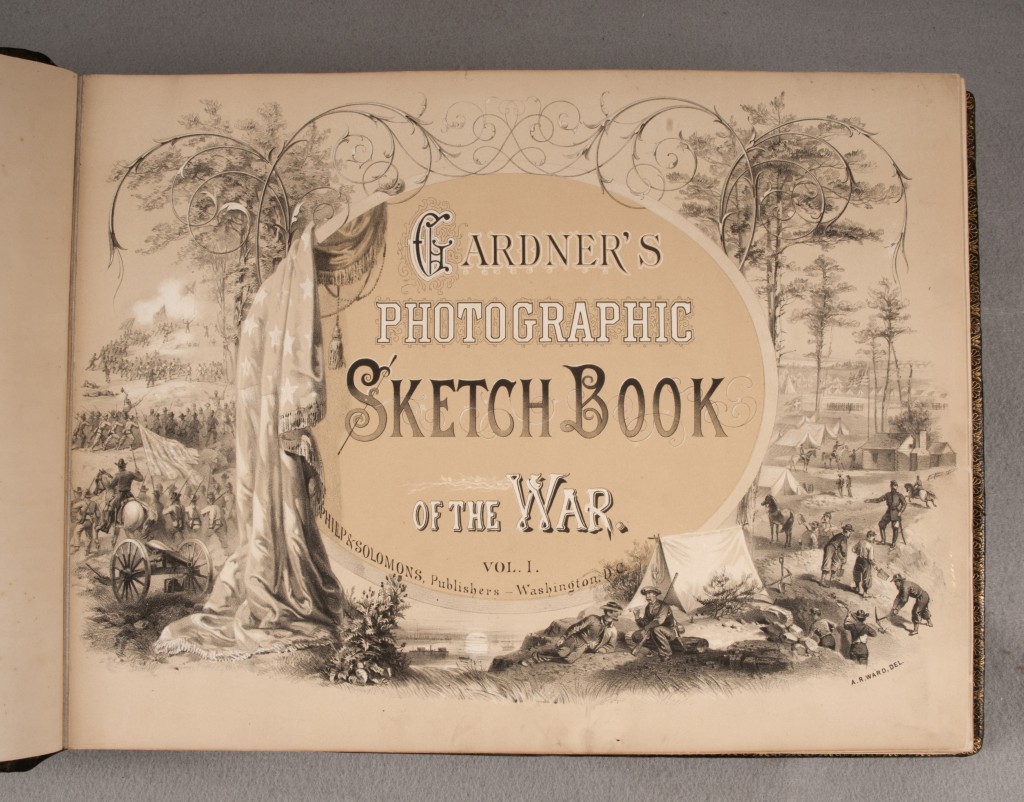

In 2013, the Rubenstein Library’s Archive of Documentary Arts celebrated two noteworthy acquisitions. Alexander Gardner’s Photographic Sketch Book of the Civil War and George N. Barnard’s Photographic Views of Sherman’s Campaign, both published in 1866, contain some of the most iconic—and graphic—images of the American Civil War. They are among the most important pictorial records of the conflict, not to mention outstanding examples of early American photography.

Soon after the photos arrived at Duke, Aaron Greenwald, Executive Director of Duke Performances, mentioned them to William Tyler, an acclaimed Nashville solo guitarist. Duke Performances has been working with the Rubenstein Library to launch a new initiative called “From the Archives,” commissioning world-class performing artists to create new works that engaged with archival materials. Greenwald asked Tyler if he might be interested in working on something about the Civil War, taking the Gardner and Barnard photographs as inspiration.

“Aaron had no knowledge that I had grown up obsessed with the Civil War,” Tyler said recently. “I agreed to do the piece on the spot.”

The result, nearly a year in the making, is Corduroy Roads, a film and music project that reflects on the lingering legacy of the Civil War, coinciding with its sesquicentennial. Tyler collaborated with filmmaker Steve Milligan and theater director Akiva Fox, both Durham residents, to create a suite for solo guitar that blends music, film, and spoken text and examines the ways in which the war continues to haunt the South to this day. The work is unlike anything Tyler has done before. (And probably unlike anything Gardner and Barnard have been involved with, for that matter.)

Corduroy Roads premiered with four sold-out performances in November at 305 South Dillard, a new multi-use arts space in downtown Durham.

The experience has been a personal one for William Tyler, a southerner with deep roots in Tennessee and Mississippi. He remembers being fascinated by the war from an early age. “It was a very present part of history,” said Tyler, who grew up in an area where every small town had its war memorials, battlefields, and historical markers. The clincher came when his parents took him to see a reenactment of the Battle of Shiloh during the war’s 125th anniversary year. “That hooked me,” he said.

Poring over the photographs by Gardner and Barnard revived that early interest. But the images also revealed things Tyler had not seen or thought about before—for example, how labor-intensive the photographic process used to be. “I don’t think people understand how fragile and delicate wet plate photography was,” said Tyler. “Our relationship with photography has changed so much over the last 150 years, from being an extension of portraiture to something that is so ephemeral it’s almost an afterthought.”

Tyler’s music offers a contemporary soundtrack to the distant past, looking at the way photography shapes our understanding of history, as well as our own personal memories.

Prior to the performance, the Duke University Libraries digitized the Gardner and Barnard photo albums, which are now freely available on our website. A century and a half later, the images still shock with the raw devastation of war. But they also preserve fleeting moments of life moving on, leaving future generations to write the history books.

Every Face in Town

Another commission by Duke Performances highlighting the creative intersection of film and music will debut this spring. Jenny Scheinman is an award-winning composer, singer, and violinist. She has toured and recorded with Bill Frisell, Norah Jones, Madeleine Peyroux, Bruce Cockburn, and many others, and has seven albums of original music to date. Scheinman was commissioned to write an original work set to seventy-year-old archival footage by the late North Carolina filmmaker H. Lee Waters.

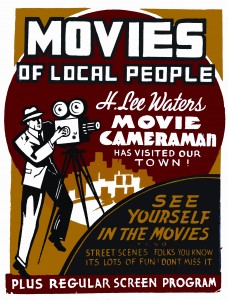

Herbert Lee Waters (1902-1997) was a studio photographer in Lexington, North Carolina. In the 1930s, he began supplementing his income by traveling to small towns across the South and filming the people who lived there going about their day. Waters worked with local movie theaters to screen his 16-mm films, which he called “Movies of Local People,” charging audience members a nickel or dime to see themselves on the big screen.

Waters produced 252 films across 118 communities in North Carolina, Virginia, Tennessee, and South Carolina, the only such collection from an itinerant American filmmaker of that era. The surviving footage, now held in the Rubenstein Library at Duke, provides a rare glimpse of everyday life in the Piedmont South during the Depression.

In 2004, the Library of Congress selected Waters’s film, Kannapolis, North Carolina, for inclusion in the National Film Registry, a list of films deemed “culturally, historically or aesthetically significant” to American culture. The film was shot in 1941, just months before the U.S. entered World War II.

It was Kannapolis that convinced Scheinman to take on the project. “It’s a particularly beautiful and joyous film,” Scheinman said. “Also, I love the fiddle and mountain music of this region. I started out as a fiddle player, and I had been looking for a project where I could get back to that again. I was living in New York at the time, and I had a little bit of artistic homesickness.”

On March 20, 2015, Kannapolis: A Moving Portrait will premiere in Duke’s Reynolds Theater. The piece blends music and film, pairing a live score by Scheinman with re-edited footage from Waters’ films. Scheinman worked with director Finn Taylor and editor Rick Lecompte to comb through fifteen of Waters’ films and choose scenes where the music and imagery would click. They also brought in sound designer Trevor Jolly to bring Waters’ silent footage to life.

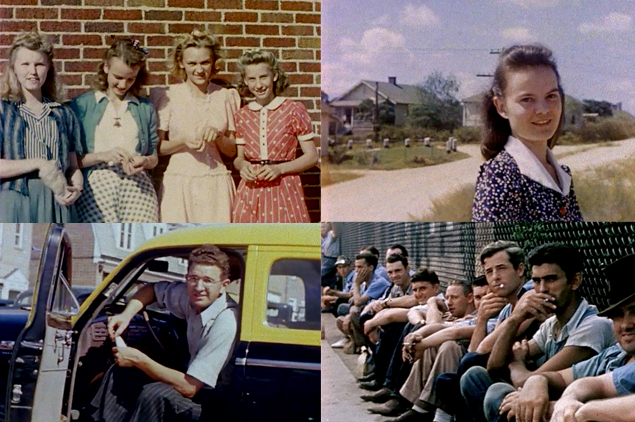

When she first watched the archival films, Scheinman was struck by how Waters managed to create a different snapshot of each community. “He would set up his camera in one town for one day, and he tried to capture every face in that town,” she said.

Waters filmed a variety of ordinary scenes, including school recitals, sporting events, and workers arriving and departing from mills and factories. He slyly included numerous shots of children to entice their families to the theater. Waters, who was white, was also one of the few filmmakers at the time to capture intimate scenes of African Americans going about their daily lives.

Without meaning to, the films reflect and critique certain things about our world today, Scheinman says. “This was before television or any modern devices. So people are very engaged with each other, very attentive and affectionate. You see them walking down the street arm-in-arm. You see people showing off for the camera, dancing, and teasing each other.”

In keeping with the time period, Scheinman’s score draws inspiration from regional folk music sources. Although she’s not from North Carolina herself—she grew up in rural California—her music, combined with Waters’ footage, conjures a powerfully resonant vision of a particular time and place in the South. The effect is not nostalgic, but plainspoken and familiar.

The Duke University Libraries are currently in the process of digitizing all 252 of Waters’ films, including Kannapolis. They will be freely available online by the end of this year. Although most of the “local people” in them have long since passed on, contemporary viewers will recognize something of themselves in the faces that still live on in the archives.