By Aaron Welborn

This is not a Christmas story, but it does begin with a very old St. Nick.

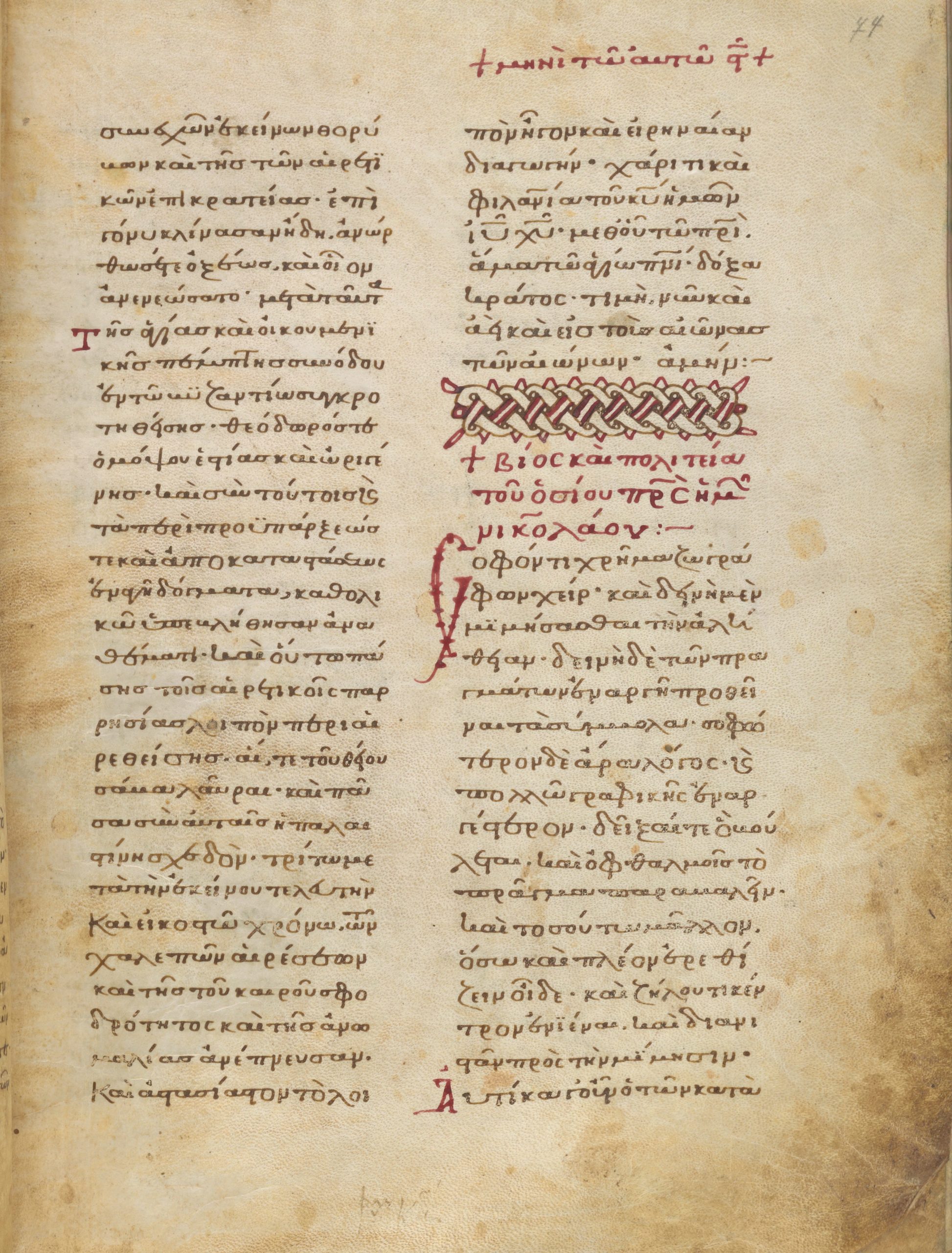

The twelfth-century Byzantine manuscript shown here recounts the life of Saint Nikolas of Myra and how he visited the home of three poor girls at night, leaving them each a bag of gold for a dowry and saving them from a life of sin. Saint Nicholas, of course, is a distant model for Santa Claus.

Known as Greek Manuscript 18 (or MS 018), it’s part of a large assemblage of ancient Greek manuscripts—one of the largest in the United States—held by the Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library at Duke.

Even for those of us who don’t read Greek, its nine-hundred-year-old parchment pages evoke the classic image of a monk painstakingly copying ancient tomes by hand. It was originally part of a much larger, multi-volume set of Eastern Orthodox saints’ lives as retold by Symeon Metaphrastes, or a “Menologion,” meant to be read aloud on certain days of the church year. This page shows December 6, the feast day of Saint Nicholas.

At some point, perhaps after World War I, the volume was brought to southern Germany, where it entered the rare book market. Years later it showed up in a London bookshop, where it was purchased on behalf of Duke in 1953.

How did a medieval manuscript migrate from Germany to London, and finally to Durham, North Carolina? According to Jennifer Knust, Professor of Religious Studies at Duke, there’s reason to believe that National Socialism had something to do with it.

Knust specializes in early Christian history and the religions of the ancient Mediterranean. She also co-directs the Franklin Humanities Institute’s Manuscript Migration Lab, an interdisciplinary collaboration among Duke scholars, students, and librarians to explore the complicated and sometimes unsettling backstories behind the oldest rare books and manuscripts in the library. The goal is to reckon with the ethical, cultural, and political questions increasingly facing libraries and museums today about their historical collecting practices. Or as Knust puts it, “Who were these manuscripts taken from, and who were they given to?”

In researching the provenance of Greek MS 018 and how it ended up at Duke, Knust discovered a troubling clue. A guide to hagiographical Greek manuscripts published in Germany in 1938 places the volume in the Ludwig Rosenthal Antiquariat, a distinguished Jewish-owned antiquarian bookstore in Munich.

In 1938, under a policy of forced “Aryanization,” the National Socialists liquidated the bookstore’s stock and deported its owner, Nathan Rosenthal, to the Dachau concentration camp. From there, Rosenthal and his wife were eventually transferred to Theresienstadt and murdered. Other members of the family fled to England and Holland and survived the Holocaust.

After the war, Duke purchased the Menologion from a London bookseller named Raphael King. When and how did the manuscript travel from Munich to King’s bookshop in London? Was it before or after the period of “Aryanization?” Conclusive evidence has yet to be discovered. “We still have a lot more work to do to determine its provenance,” said Knust, who continues to research the document’s history.

It’s important work with real-world implications. “Duke has one of the largest collections of ancient Greek manuscripts in the country,” said Knust. “That’s a tremendous opportunity, but it’s also a tremendous responsibility. One of the things I love about this library is its willingness to be transparent and public about what’s in our special collections.”

By examining the historical, political, and market forces that brought such collections to Duke, we can better appreciate their importance as survivors and witnesses to history.

This is one of several documents on display as part of the exhibit, Manuscript Migration: The Multiple Lives of the Rubenstein Library’s Collections, running through February 3, 2024, in the Mary Duke Biddle Room. The exhibit was curated by students, faculty, and affiliates of the Manuscript Migration Lab in the Franklin Humanities Institute.