Collection Chronicles Social, Cultural, and Historical Impact Over 80 Years

By Aaron Welborn, Director of Communications

The David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library at Duke University has acquired the archives of Consumer Reports (CR), the mission-driven nonprofit consumer organization, committed to creating a fair, safe, and transparent marketplace for consumers.

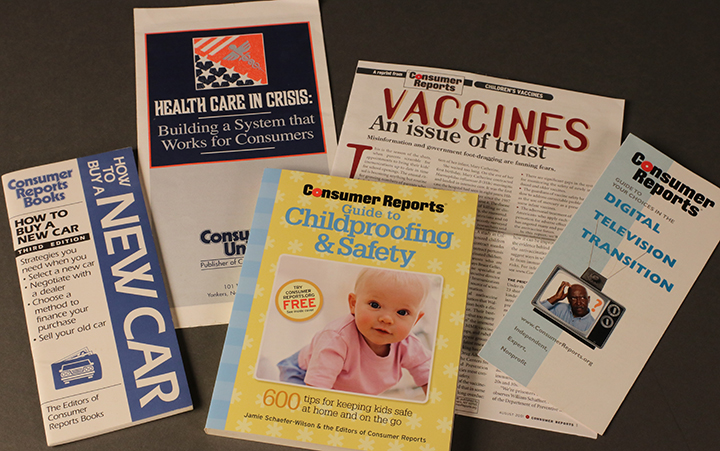

The massive collection—which spans some 2,800 linear feet and required two tractor trailers to transport to Durham from CR’s headquarters in Yonkers, New York—includes archival materials, books, photographs, and artifacts documenting the history of the organization from its founding during the Great Depression to its eventual prominence as a household name for safety, reliability, and informed decision-making.

As the collection reveals, that reputation was long and hard in the making. “Even many longtime Consumer Reports members would likely be surprised by the organization’s colorful and controversial history,” said Jacqueline Reid Wachholz, director of the Rubenstein Library’s Hartman Center for Sales, Advertising, and Marketing History, where the collection will formally reside.

It began in February 1936, when a group of journalists, academics, engineers, and labor leaders founded Consumers Union, a membership organization dedicated to scientifically testing common products and services, educating the public, and aiding consumers “in their struggle as workers, to get an honest wage.”

Three months after the organization formed, the first issue of Consumers Union Reports appeared, featuring articles on breakfast cereals, Alka-Seltzer, toilet soaps, stockings, milk, toothbrushes, lead in toys, and credit unions.

From a few thousand initial members, the magazine quickly grew to a circulation of 37,000 by the end of its first year, and 85,000 by 1939. Its rapid success was notable, given the opposition from the business community and the commercial press, which viewed the publication and the fledgling consumer movement it represented as a radical threat to corporate interests.

More than sixty newspapers and magazines, including the New York Times, refused to sell advertising to Consumers Union, on the basis that consumer product testing represented “an unfair and subversive attack upon legitimate advertising,” according to Norman Silber in his authoritative history of Consumers Union, Test and Protest (1983).

During the organization’s early days, it advocated on behalf of unionized workers who produced the kinds of products featured in its pages. “By reporting on labor conditions under which consumer products are produced,” wrote the magazine’s editors in the inaugural issue, “Consumers Union hopes to add what pressure it can to fight for higher wages and for unionization and the collective bargaining which are labor’s bulwark against declining standards of living.”

Such statements earned Consumers Union the ire of powerful corporate interests and politicians, who branded it as “anti-capitalist” and even communist. From 1944 to 1954, Consumers Union was actually blacklisted as a subversive organization by the House Un-American Activities Committee, a charge that was only lifted after years of legal protests. The organization’s leadership, including economist Colston Warne and engineer Arthur Kallet (both of whose papers are included in the collection), suffered similar character attacks for their outspoken support of product safety standards, government regulations, and other measures—largely uncontroversial today—that put consumer interests over corporate profits.

Eventually, the magazine’s editorial emphasis shifted towards more scientific testing and trusted consumer guidance. Its refusal to accept paid advertising, or free samples from manufacturers, bolstered the publication’s claim to independence, nonpartisanship, and credibility. The magazine’s member base continued to grow, especially during the prosperous postwar era, when consumer spending boosted the economy and a growing middle class was hungry for advice on what to buy.

Today, Consumer Reports reviews approximately 2,500 products and services across more than one hundred categories, and it reaches tens of millions of people through print, digital, and broadcast media, which includes the network television series Consumer 101 on NBC and Taller del Consumidor on Telemundo.

In addition to its consumer research, product testing, and investigative journalism, Consumer Reports leads far-reaching policy and advocacy initiatives, working to secure pro-consumer policies in government and across industries. Over the course of its history, the organization has played an influential role in championing pro-consumer protections and rights in the automobile, food, healthcare, and financial services industries, as well as the creation of several government safety commissions.

In 1953, Consumer Reports was the first publication to warn consumers about the dangers of cigarettes. Its research and reporting eventually led the U.S. Surgeon General’s landmark report on smoking in 1964. The organization’s advocacy efforts were also instrumental in the U.S. government mandating seat belts in all automobiles (1968), stricter standards for child safety seats (1981), and a ban on the chemical Bisphenol-A (BPA) in baby bottles and sippy cups (2012). In 2010, Consumer Reports played a significant role in mobilizing congressional support for the creation of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, among other regulatory measures it has championed.

In its new home in Duke’s Rubenstein Library, the Consumer Reports archive complements existing collection strengths, including the Hartman Center—home to the largest collection of materials on the history of advertising and marketing in the U.S.—and the Economists’ Papers Archive, which holds the papers of more than sixty significant economists.

“In our current modern society, where trust in institutions and the marketplace have eroded, the legacy and mission of Consumer Reports have never been more relevant,” said Marta L. Tellado, President and CEO of Consumer Reports. “The rich social, cultural, and historical impact of CR is essential to share not because it belongs to the past, but because it is as urgent today as it has ever been—at a moment when the stakes could not be higher for consumers, and when we must fight even harder to keep the market honest.”

The collection has already attracted the interest of researchers and Duke faculty. “Through the acquisition of this remarkable archive,” noted Duke Vice Provost and historian Edward Balleisen, “we have further solidified the Rubenstein Library’s status as a pivotal repository for the study of modern American capitalism. For historians and other social scientists who wish to research or teach about economic life during the American century, the Consumer Reports collection will beckon as an essential source of evidence about technological change, consumer culture, business-state relations, the evolving dynamics of consumer protection, and non-governmental arbiters of quality and value.”

It will take approximately three to four years to catalog the archives, the majority of which will be open to researchers.