What History Can Tell Us Through a Single Document

By Keegan Trofatter

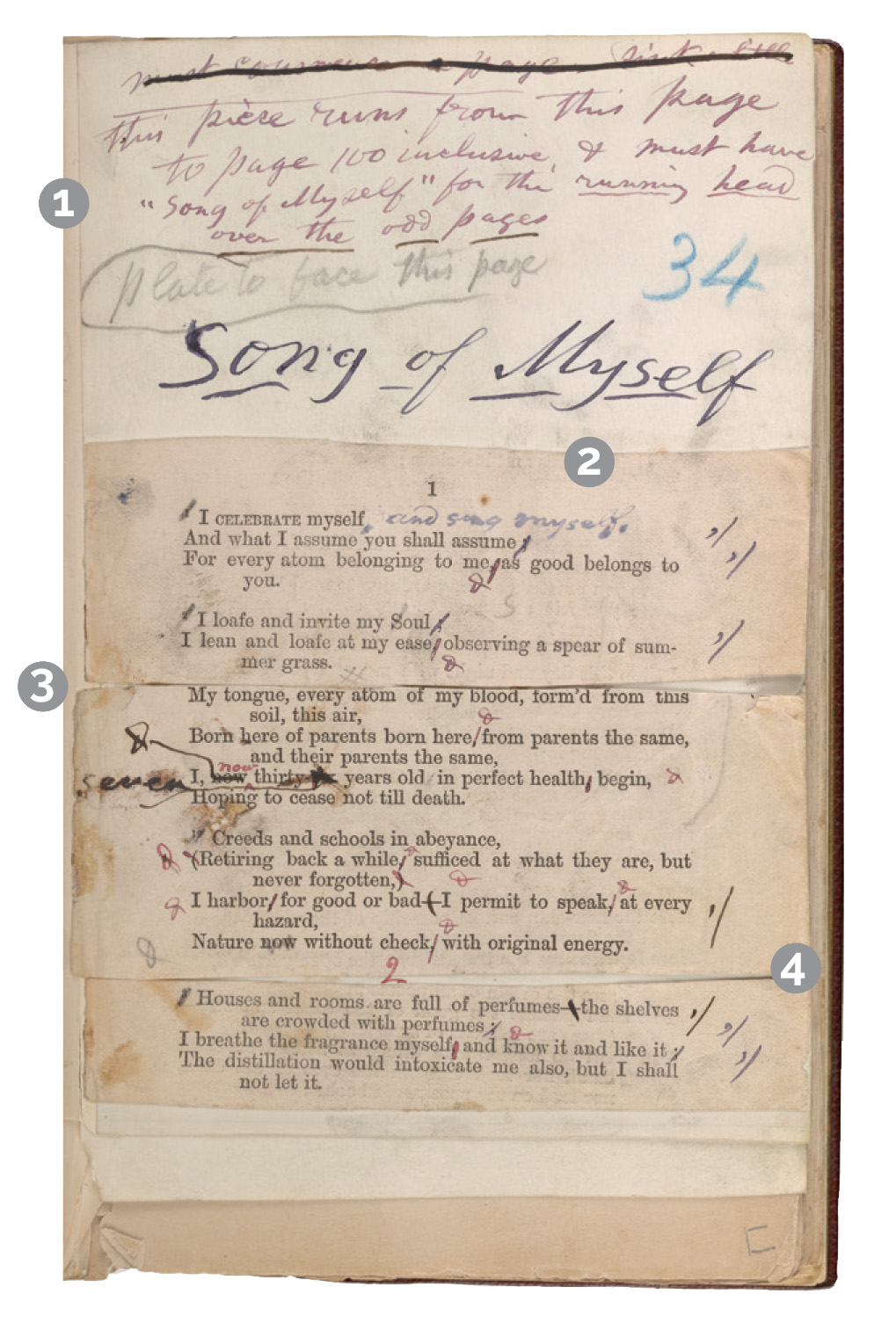

Walt Whitman was born two hundred years ago this spring (May 31, 1819) in West Hills, New York. In honor of his bicentennial, this is a page from the printer’s proof of the 1881 edition of Leaves of Grass, the most famous work of America’s most famous poet. The proof is riddled throughout with corrections, additions, instructions to the printer, and re-ordered page numbers, all in Whitman’s own hand. It is one of thousands of original manuscripts, printed works, and other “Whitmaniana” (including a lock of the poet’s hair) given to Duke by Dr. and Mrs. Josiah Charles Trent in 1942 and housed in the Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library. Today it stands as one of the largest and most important Whitman collections in the world.

1

In 1855, at the age of thirty-six, Whitman self-published the first edition of Leaves of Grass. Over the course of twenty-seven years and nine different editions, the collection expanded from the twelve original, untitled poems to over four hundred complete ones. Not only did Whitman add more poems with each subsequent edition, but he meticulously and continuously revised them all. When interviewed about the publication of the 1881 edition, Whitman said, “This edition will complete the plan which I had outlined from the beginning. It will be the whole expression of the design which I had in my mind.” (As it turned out, he went to work one final time to publish what is now known as the “deathbed edition” of 1891-92.) Here Whitman instructs the printer that he wants the title of the section to appear as “the running head over the odd pages.” It’s just one of many examples of the poet’s perfectionism and desire to control every aspect of the way his life’s work was presented. Apparently Whitman loved this part of the editorial process. He writes in a note to himself, “Having been in Boston the last two months seeing to the ‘materialization’ of my completed ‘Leaves of Grass’—first deciding on the kind of type, size of page, head-lines, consecutive arrangement of pieces; then the composition, proof reading, electrotyping, which all went on smoothly, and with sufficient rapidity. Indeed I quite enjoyed the work, (have felt the last few days as though I should like to shoulder a similar job once or twice every year).”

2

Whitman’s best known poem, “Song of Myself,” was not titled as such until the 1881 edition of Leaves of Grass. In previous editions it was titled, “Poem of Walt Whitman, an American,” or simply the author’s name, “Walt Whitman.” Here, in this line of penned cursive, we can see the stroke of inspiration when Whitman settled on the final title for the piece for which he is best remembered. It is interesting to note an edit further down the page where Whitman lengthens the first line “I celebrate myself,” by adding “and sing myself,” bringing the poem in parallel with the title. Whitman once wrote, “My Poems, when complete, should be A Unity.” These mirrored inclusions of “song” and “singing” are just one step the poet took to unify his work along cohesive themes.

3

For efficiency’s sake, Whitman used a previous printed edition of Leaves of Grass as the basis for his edits to the 1881 version. He literally cut and pasted lines from different pages together. In some cases, he even excised individual words and wrote in substitutions, leaving rectangular holes in the manuscript. This cutting may have also stemmed from his desire to regroup the poems into subtitled sections and clusters, a formal device he had been experimenting with. In fact, in the course of regrouping the poems, many of them did not make the final cut. The 1881 edition of Leaves of Grass saw thirty-nine previously published poems left out and seventeen new ones inserted.

4

Of all the edits Whitman made throughout the printer’s proof, hundreds are mere changes of punctuation. We can see him cutting em dashes and commas from the lines, or in some cases relocating them, changing the rhythm of the verse and placing the emphasis on new phrases. Though we are left to wonder about his sudden aversion to the comma, perhaps the words of a contemporary critic can provide insight. A review in the Washington Daily National Intelligencer from 1856 reads, “Walt Whitman is a printer by trade, whose punctuation is as loose as his morality, and who no more minds his ems than his p’s and q’s.” While this may seem a harsh (and oddly specific) critique, it is exemplary of the public’s fascination with Whitman as a celebrity writer. The bard offered the world a bold, mysterious portrait of an artist and invited readers to question his work, from the controversial thematic elements to the smallest of stylistic choices.

Keegan Trofatter (T’19) is an English major and student worker in the Library Development and Communications department.