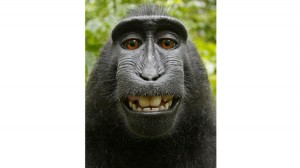

By now, most people know about the macaque monkeys that took pictures of themselves in the Indonesian jungle, and the controversy over who, if anyone, owns a copyright in the resulting pictures. The events actually took place several years ago, but the popular news media has recently picked up the story because of threats by the photographer whose cameras were used, David Slater, to sue Wikipedia if the photographs, which Slater says are his intellectual property, are not taken down. Wikipedia refused his take down request, and the story has gone viral. I know a copyright story has penetrated into popular culture when I am asked about it at home, over the dinner table!

There has been so much commentary, including an impassioned defense of the rights of monkey artists, that I am hesitant to wade into the fray. But I think there are some lessons we can learn from both the story and people’s reaction to it; there is an opportunity here to remind ourselves of some basic principles about copyright law.

There has been so much commentary, including an impassioned defense of the rights of monkey artists, that I am hesitant to wade into the fray. But I think there are some lessons we can learn from both the story and people’s reaction to it; there is an opportunity here to remind ourselves of some basic principles about copyright law.

So let my offer two comments about the controversy itself, and two comments about the public reaction to it.

First — cards on the table — I am inclined to believe that these photos do not have any copyright protection because they lack any element of human agency. The fundamental principle of copyright law, stated very early in the U.S. law, is that copyright protects “works of authorship.” And although I never really thought the idea would be challenged, I think authorship implies human agency. There must be a spark of creative, a decision to create a work, for something to be a work of authorship, and these photos do not have that. The story has shifted a bit over time, but it does not appear that Mr. Slater gave his cameras to the monkeys deliberately. Even if he did, that could hardly be called a creative decision. He had no control over what they did with the cameras; they were as likely to smash them on the ground as to take pictures.

In the well-known Feist decision about the white pages of phone books, the Supreme Court discussed the idea of a work of authorship, and told us that mere hard work — sweat of the brow, as they said — does not by itself earn copyright protection. A work of authorship must be original in the sense of not copied, but it also must have a spark of human creativity. It need not be much, but some human decision is required.

By the way, the Feist decision is a roadmap to why Mr. Slater’s arguments about the money and effort that went into his photo-taking trip to Indonesia do not succeed in convincing me that he should have a copyright in these specific photos. His other argument, that the monkeys stood in the shoes of a hired assistant, such that Mr. Slater should own the copyright in these photos as the “employer,” also fails, if it were ever seriously proposed. For one to be an independent contractor, human agency is again required. In U.S. law, there must be an explicit agreement before any copyrighted work created by an contractor could be considered work for hire. And monkeys do not have legal capacity to enter into a contract. This is a legal point; no matter how smart other creatures are or the degree to which humans should recognize animal rights, the law, including copyright and contract, deals with relationships between human beings.

Human relations are the foundation of my other legal point about this situation. We need to remember that copyright has a specific incentive purpose; it is designed to reward creators so that they will continue to create. The law grants a government-enforced monopoly so that authors and other creators can make enough money to support their creative efforts. And this justification completely fails when the creator is not a participant in human society. Granting a copyright in a monkey-taken photograph would be a mockery of the incentive purpose of the law.

Mr. Slater seems to argue the incentive purpose of copyright when he asserts that it takes a lot of hard work and investment to be a photographer, and only a few of the many photos he takes will make any money. All true, I am sure, but not relevant. This is not a photo that he took, and it does not meet the standard of a work of authorship eligible for the peculiar legal structure we humans call copyright. Many reactions to this story have focused on the idea that it is somehow unfair to deny Mr. Slater profit from the photo. But copyright law is not about fairness, nor does it exist to reward industry or protect an investment. Laws are passed for many purposes, and fairness is often well down on the list of reasons. It is silly to expect to be able to use copyright to leverage some result considered “fair” in every situation that involves an (apparently) creative work.

My final observation about the reactions this story has provoked is actually eloquently made by Mike Masnick of TechDirt when he writes about “How that monkey selfie reveals the dangerous belief that every bit of culture must be owned.” It is curious to see how uncomfortable many people are with the idea that no one at all owns these photos; that they are therefore the property of everyone. Perhaps it is the unfortunate influence of the big content industries that makes some people uncomfortable with the idea of the public domain. One of the early articles in this new round of media coverage asked its readers to vote on who owned the copyright in the photo. Most voters split between Mr. Slater and the monkey, with less than 17% being willing to assert that no one owned it, it was in the public domain. And apparently Wikipedia has decided to let the public vote on continuing to make the photo available.

Maybe the real lesson we should take from this silliness is that the public domain is real, and it is important. Much of human culture would not have been possible without free access to our shared literary and artistic heritage. The U.S. Constitution builds a public domain in to the very words by which it gives Congress the power to pass copyright laws, by requiring that those rights be “for a limited time.” We cannot have copyright without a public domain; to attempt that would be cultural suicide. So we need to learn not just to accept the public domain, but to celebrate it. Perhaps that is why the monkey is smiling,