NOTE — Authorship can be a tricky thing, impacted by contractual agreements and even by shifting media. In this guest post by Jennifer Ahern-Dodson of Duke’s Thompson Writing Program we get an additional perspective on the issues, one that is unusual but might just become more common over time It illustrates nicely, I think, the link between authorship credit, publication agreements and a concern for managing one’s online identity. A big “thank you” to Jennifer for sharing her story:

Signing My Rights Away

Jennifer Ahern-Dodson

I stared at my name on the computer screen, listed in an index as a co-author for a chapter in a book that I don’t remember writing. How could I be published in a book and not know about it? I had Googled my name on the web (what public digital humanist Jesse Stommel calls the Googlesume), as part of my research developing a personal website through the Domain of One’s Own project, which emphasizes student and faculty control of their own web domains and identities. Who am I online? I started this project to find out.

I was taken aback by some of what I found because it felt so personal—my father’s obituary, a donation I had made to a non-profit, former home addresses. All of that is public information, so I shouldn’t have been surprised, but then about four screens in I found my name listed in the table of contents for a book I’d never heard of. Because the listed co-author and I had collaborated on projects before, including national presentations and a journal publication, I wondered if I had just forgotten something we’d written together.

I emailed her immediately and included a screenshot of the index page. Subject line: “Did we write this?”

She wrote back a few minutes later.

WHAT??!!! We have a book chapter that we didn’t even know about???!!!!! How is this possible? Ahahahahahahahaha!!!!!

It’s a line for our CV! But, wait, what is this publication? Do we even want to list it? Would we list it as a new publication? Is it even our work? How did this happen?

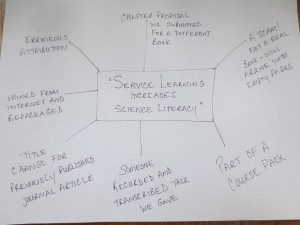

This indeed was a mystery. At the time this was all unfolding, I was participating in a multidisciplinary faculty writing retreat. Once I shared the story with fellow writers, they enthusiastically joined in the brainstorming and generated a wide range of theories including plagiarism, erroneous attribution, a reprint, and an Internet scam (see Figure below). I mapped the possibilities for this curious little chapter called “Service Learning Increases Science Literacy,” listed on page 143 of the book National Service: Opposing Viewpoints (2011)[1].

I needed to do more research and so requested the book through Interlibrary Loan and purchased it online as well.

And then there was the story of the editor. Who was she? Did she really exist? Was she a robot editor—just a name added to the front of a book jacket? I started wondering, now that so much of our work is digitized, are robots reading—and culling through—our work more than people? A quick search on Google revealed she was the editor for over 300 books, mostly for young adults. Follow up searches on LinkedIn and Google+ revealed profiles that seemed authentic.

The book arrives.

About a week later, the book arrived through Inter-library Loan. While still standing at the library service desk, I quickly flipped to page 143.

What I discovered is a reprint (with a new title) of an article my author and I had published in the Journal of College Science Teaching.[2] It was republished with permission through the journal, conveyed through Copyright Clearance Center. The table of contents included a range of authors and works, including an

excerpt from a speech by George W. Bush.

It all looked legitimate. But how could I be published and not know about it?

In an email conversation with Kevin Smith, my university’s scholarly communication director and copyright specialist, I learned that typically in publication agreements, authors transfer copyright to the organization that publishes the journal. From then on, the organization has nearly total control. It can do what it wants with the article (like republish it or modify it), and for most other uses I might want to make (like including it on my website), I’d have to ask their permission.

I also learned that republication is not uncommon. Although this book is marketed as “new,” it is in fact really just repackaged material from other sources that libraries likely already have. In this case, our article for a

college teaching journal was repackaged for an audience of high school teachers as part of an opposing viewpoints series, essentially marketing the same content to a different audience.

In a slightly different repackaging model, MIT Press has started re-publishing scholarly articles from its journals in a thematically curated eBook series called Batches.

These two models made visible for me the ways that copyright, institutional claims, and the Internet fuel change at a pace so rapid it seems almost impossible for authors to keep up.

Where to go from here

Although the ending to this mystery is not as thrilling as I thought it would be (someone plagiarized our work! Someone recorded and transcribed a talk! The book is a scam!), what I uncovered was this whole phenomenon of book republishing. Our chapter was legitimately repackaged in a mass marketed book with copyright secured, which allowed our work to be shared with a broader audience (which I see as a good thing). Yet, the process distanced me from my work in a way I was not expecting. In my naïve, yet I suspect widely held view of academic authorship, I assumed the contract I had signed was simply a formality, more of a commitment by the journal to publish the article and an agreement by my co-author and me to do so. I only skimmed the contract, distracted perhaps by the satisfaction of getting published and the opportunity to circulate my ideas more broadly.

As I submerged myself into the murky depths of republishing, I started to think about my own responsibility as both a writer and a teacher of undergraduate writers, to educate myself on authors’ rights. Could I negotiate publishing agreements to retain copyright? Or, at the very least, could I secure flexibility to re-use my work? As it turns out, yes. The Scholarly Publishing and Academic Resources Coalition has created an Author Addendum to help authors manage their copyright and negotiate with publishers rather than relinquishing intellectual property.

Although it is not uncommon for publishers to ask authors to sign over their legal rights to their work, at least one publisher—Nature Publishing, which includes the journals Scientific American and Nature—goes even farther. It requires authors not only to waive their legal rights but also their “moral rights.” Under this agreement, work could conceivably be republished without attribution to the original author. There was a story about this a couple of months ago, see http://chronicle.com/article/Nature-Publishing-Group/145637/.

In my case, I clearly did not do due diligence as an author when I read and signed the agreement for the science literacy article, and neither the journal nor the book editor or publisher was under any legal obligation to notify me that my work was republished or retitled. I wonder, however, what would happen if we applied the concept of academic hospitality to our publishing relationships. Could a simple email notification when/if our work gets republished be a kind of professional courtesy we can expect? Or, should we as authors get more comfortable with less control over our work and choose to share our ideas more liberally in public domains in addition to academic journals, which have limited readership and at times draconian author agreements? Do institutions have any role to play in educating their faculty and graduate students about signing agreements?

In my quest to create a domain of my own, to “reclaim the web” and be an agent in crafting my own author identity online, I discovered that, in fact, I had given up control of some of my own work. Now, I’m aware of the need to balance going public with my work—both online and in print—with a thoughtful and informed understanding of my rights and responsibilities as an academic author.

[1] Gerdes, Louise, Ed. Greenhaven Press.

[2] Reynolds, J. and Ahern-Dodson, J. “Promoting science literacy through Research Service-Learning, an emerging pedagogy with significant benefits for students, faculty, universities, and communities.” Journal of College Science Teaching 39.6 (2010).

Thank you, Jennifer, for sharing this “alert” and the steps you took. This is “proof” for the skeptics.

A thoughtful, balanced and thought-provoking essay about the rapidly changing circumstances of scholarly publication in the internet age. I like Jennifer’s nuanced approach. She steers clear of both internet euphoria and internet paranoia, reminding us that the solutions aren’t simple and that being mindful and knowledgeable is always the best first step.

It’s helpful for me to know that I’m not the only one who gets confused about these things! I will share Jennifer’s very real experience with students who, in their beautiful enthusiasm for sharing ideas, don’t always think carefully about the bigger picture.