Post contributed by Dr. Paul Sommerfeld, Rubenstein Graduate Intern for Manuscripts Processing and one of Duke’s newest PhDs in the Dept. of Music.

By the age of 26, John Armstrong Chaloner (1862-1935)—or to his friends, Archie—had amassed a fortune of $4 million and seemed poised to live the privileged life the wealthy elite of New York City enjoyed in the late nineteenth century. In 1897, however, his family had him involuntarily committed to a psychiatric hospital. Chaloner spent the next 22 years fighting to prove his sanity. His papers, a mixture of correspondence, legal documents, and writings by Chaloner himself, offer not only a fascinating portrait of Chaloner but also a snapshot of attitudes toward mental health in the early twentieth century.

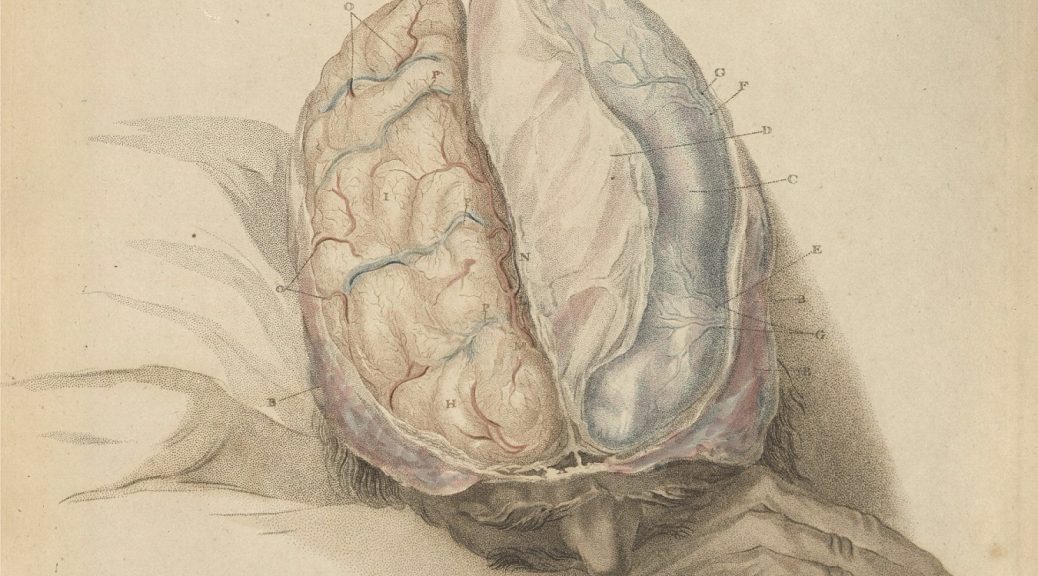

In the 1890s, Chaloner became interested in psychological experiments. He believed that he possessed a new sense, which he termed the “X-Faculty.” Among many claims, Chaloner stated that the faculty provided him a profitable stock market tip, would turn his brown eyes gray, allowed him to carry hot coals in his hands unharmed, and caused him to resemble Napoleon.

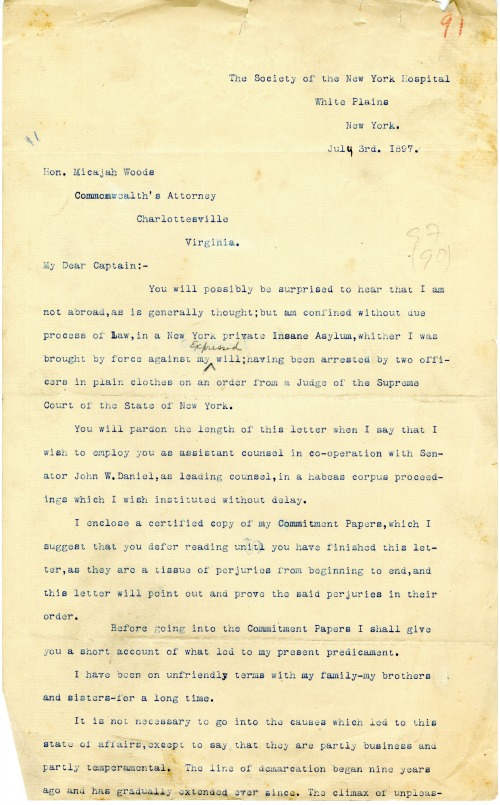

Chaloner’s family regarded his claims—in addition to his blasé attitude toward the scandal of his divorced wife, the novelist Amélie Rives—as evidence of insanity. Chaloner continued to live near Rives’ estate in Albemarle County, VA, and even befriended her second husband. Chaloner’s brother reportedly labeled him as “looney.” In response, Chaloner’s family had him committed to the Bloomingdale Hospital in White Plains. On 12 June 1899, a New York court declared him insane and ruled that he be permanently institutionalized.

But Chaloner had other plans. He believed his family had him committed to seize his fortune and stop his experiments. Bitter sonnets composed during his time at the asylum reflect his anger and desire to clear his name. In November of 1900, he managed to escape to a private clinic, whose doctors declared him able to function in society. Thereafter, Chaloner plotted strategies to both overturn the New York verdict and change lunacy laws in America.

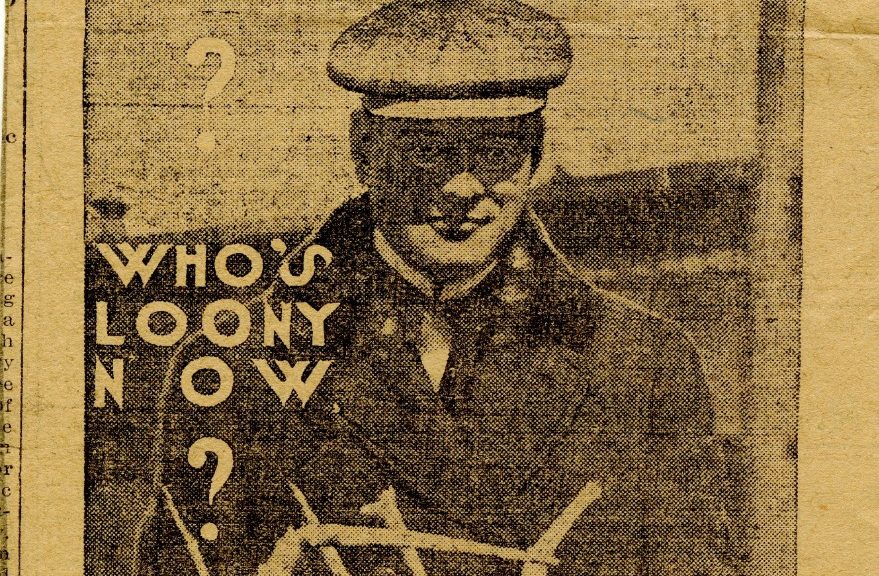

During his legal challenges, Chaloner became immortalized by the phrase “Who’s looney now?.” In the summer of 1910, Chaloner’s brother married the opera singer Lina Cavalieri and signed over control of his property to her. The marriage soon broke down, and Chaloner wired his brother the pithy catchphrase. Four years later Chaloner even titled one of his many books The Swan-Song of “Who’s Looney Now?” (1914), drawing on the phrase’s subsequent popularity.

Chaloner’s correspondence, copious notes, and book drafts speak to his dedication in clearing his name. Filled with legal strategy and instructions to attorneys in New York, North Carolina, and Virginia, his letters trace his maneuvering within the legal system, reaching even the U. S. Supreme Court in 1916. In Chaloner v. Thomas T. Sherman, Chaloner sought damages for the withholding of his estate and fortune. Chaloner argued that because he was a resident of Virginia, New York had no jurisdiction. Unfortunately, the Supreme Court affirmed the U. S. Circuit Court of Appeal’s decision.

Yet the courts of Virginia and North Carolina had declared Chaloner sane in 1901, allowing him to live and maintain business interests in both states. New York continued to declare him legally insane until 1919, when his family no longer challenged the petition and reconciled with Chaloner.

Like his dogged legal challenges, Chaloner’s book drafts, including Four Years Behind the Bars of “Bloomingdale,” or, The Bankruptcy of Law in New York (1906) and The Lunacy Law of the World: Being That of Each of the Forty-Eight States and Territories of the United States, with an Examination Thereof and Leading Cases Thereon; Together with That of the Six Great Powers of Europe—Great Britain, France, Italy, Germany, Austria-Hungary, and Russia (1906), are also filled with annotations and revisions that fill every bit of available white space. Not even a calendar from the University of Virginia escaped unscathed.

Chaloner’s papers offer a fascinating portrait into the mind of a determined, if eccentric, man, while also simultaneously portending the burgeoning changes toward psychiatry in both medicine and the law that developed throughout the twentieth century.

The John Armstrong Chaloner Papers are available for research.

But then, as I was browsing our library catalog, I came across 401 Party and Holiday Ideas from ALCOA (Aluminum Company of America, 1971) in our

But then, as I was browsing our library catalog, I came across 401 Party and Holiday Ideas from ALCOA (Aluminum Company of America, 1971) in our

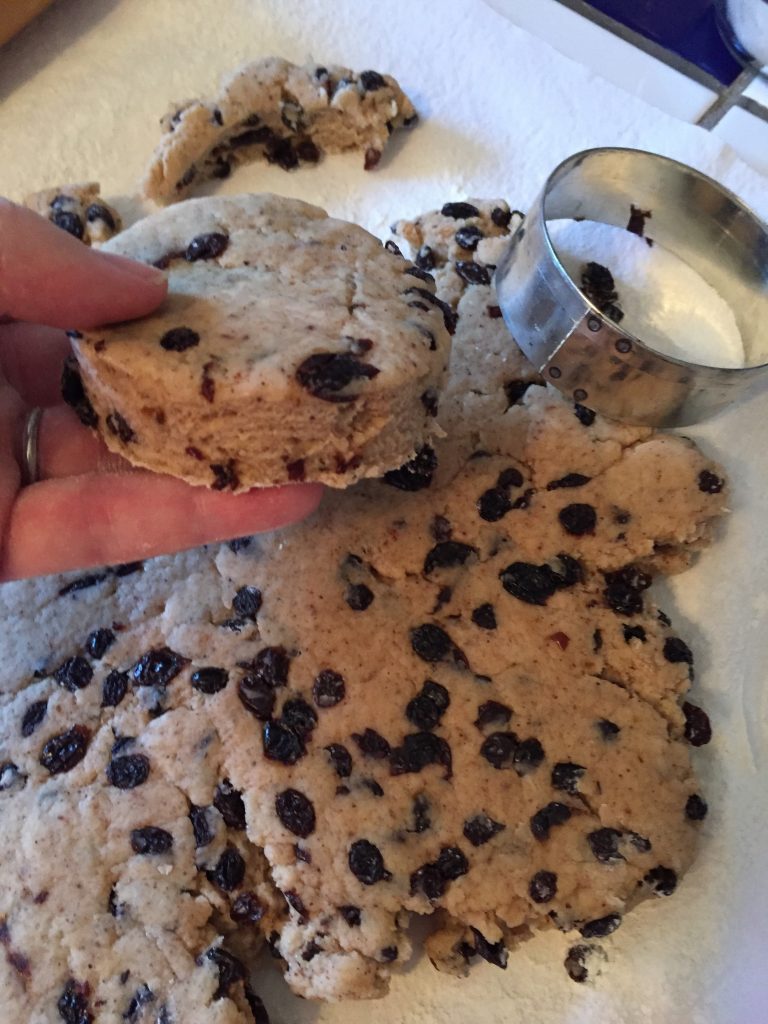

But this 1971 recipe just called for an 8-inch cake pan in a regular oven, and that’s what I used. I was making this in my mom’s kitchen, so I got to use the sifter that had belonged to her mom. Mom told me we had relatives from County Kerry, too.

But this 1971 recipe just called for an 8-inch cake pan in a regular oven, and that’s what I used. I was making this in my mom’s kitchen, so I got to use the sifter that had belonged to her mom. Mom told me we had relatives from County Kerry, too.

Join the Bingham Center for a two-day event celebrating the history and future of the Re-imagining Movement.

Join the Bingham Center for a two-day event celebrating the history and future of the Re-imagining Movement.