“DINNER is the only act of the day, which cannot be put off without Impunity, for even FIVE MINUTES.”

William Kitchiner, The Cook’s Oracle, “Invitations to Dinner,” p. 39.

English cooking is a punch line. You don’t even need a joke to set it up. Just say, “English cooking,” and people start smirking, or chortling, even suppressing laughter. It hardly seems fair.

After all, Great Britain boasts its share of culinary scores. The Scotch egg is a triumph of human ingenuity, I’ll take a ploughman’s lunch any day of the week, and the standing rib roast with Yorkshire puddings rates as a time-proven classic. Really, America, with your pit-cooked barbeques and New York-style slices, don’t be so glib. Arthur Treacher would like a word.

When I volunteered to write a Rubenstein Test Kitchen post, I had no real ideas for it, but set out on a path of discovery, like Walter Raleigh sailing for Carolina.1 I can’t remember how I came across William Kitchiner’s proto-Victorian cookbook, The Cook’s Oracle, in our catalog, and learned that the History of Medicine Collection holds a copy of the Fifth Edition, published in 1823. But I can tell you that I was drawn to it by one word: Wow.

More particularly, it was that word, twice. I learned that Kitchiner is credited as the inventor of a thing called Wow Wow Sauce, an accompaniment for boiled meat dishes. Intriguingly, the recipe includes two English condiments I never knew existed: pickled walnuts, and mushroom catsup.

How – I asked myself – could I not cook something called Wow Wow Sauce? The answer is, I couldn’t. I couldn’t not cook Wow Wow Sauce.

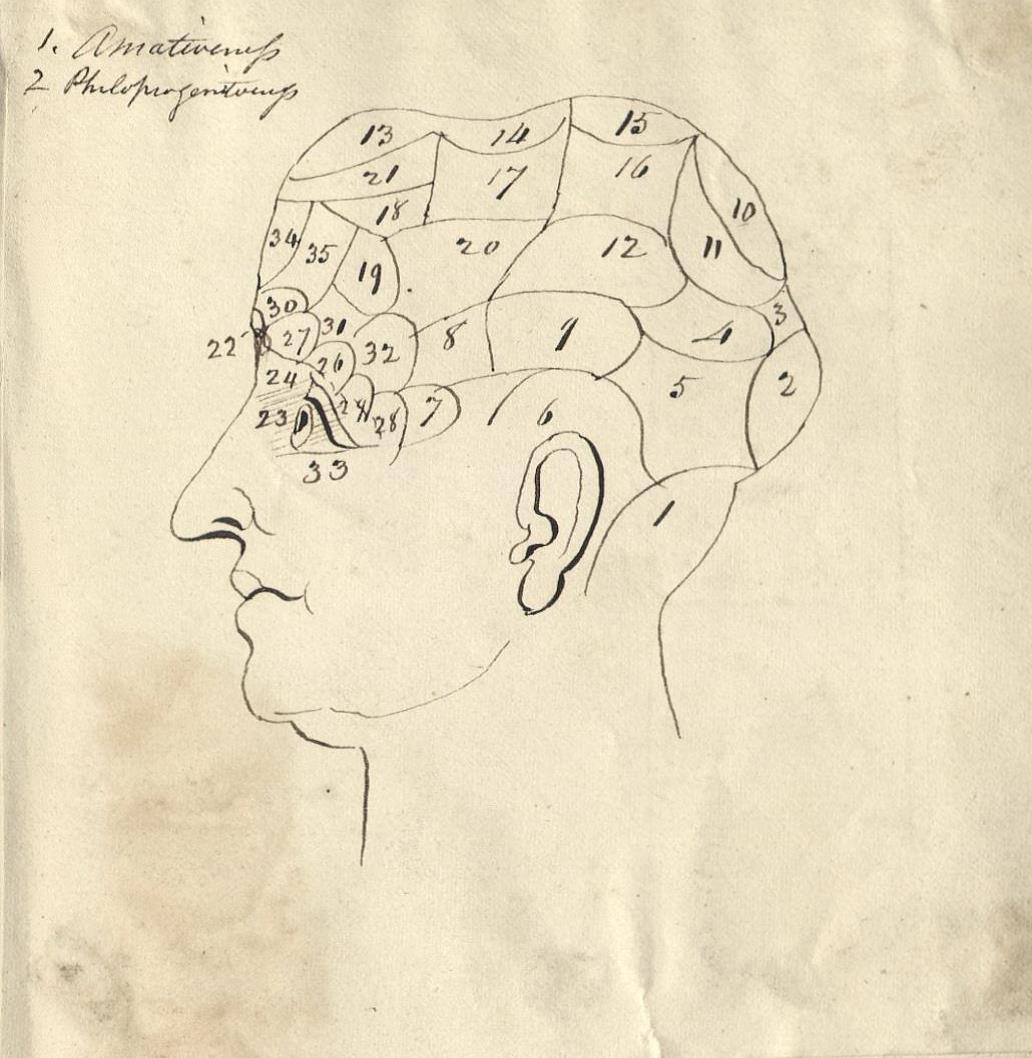

Kitchiner was a physician by profession, but seems to have been stern and serious in his approach to cooking and socializing. His cause was to bring scholarly and scientific order to the chaotic affairs of households and kitchens. Wikipedia claims his name was a household word and the book a best-seller. Chambers’ Book of Days, a miscellany published in 1879, provides background on his life and habits.

So the two recipes I select from Kitchiner’s book are Shin of Beef Stewed (No. 493), and Wow Wow Sauce for Stewed or Bouilli Beef (No. 328). The first order of business is to secure the ingredients, and in this effort I turn to two eminent local suppliers. First, I head to Southern Season in Chapel Hill, on whose shelves I locate both Opie’s brand pickled walnuts and George Watkins brand mushroom catsup.

Second, I need meat. Now, I happen to live in the town of Pittsboro, where I’m lucky to shop with Lilly Den Farm at the Chatham Mills farmers’ market each week. Tucker and Mackenzie’s place is out past Goldston, down in what’s called Deep Chatham. They hook me up with a nice-looking foreshank, a shin indeed, nearly two feet long and heavy with marbled meat. It’s covered in a tough membrane, which I skin off with a knife. Then I coat the whole thing in a generous amount of kosher salt, wrap it, and store it in the fridge overnight.

The next day, just before noon, I set the shank in a pot, cover it with cold water, and bring it to a simmer.

Usually, one buys a beef shank this size cut crosswise into two or maybe three discs. The flat surfaces from these cuts are convenient for seasoning and placing in a hot, oiled pan for browning, which produces the Maillard reaction, enhancing the flavor of the meat and leading to a rich, brown broth.

But that’s not what I’m looking for here. Yes, Kitchiner himself recommends a shank cut into sections (and doesn’t mention browning), but I prefer the shin intact. No fancy Maillard crust for my Test Kitchen project. I honestly can’t describe my vision better than this Guardian author: “The grisly, gristly spectre of an ashen Victorian joint – a lump of cracked cement flanked by dismal sprigs” – Yes! That’s exactly what I’m going for, and by the way, I love your accent, please do continue – “speaks of cabbagey kitchens and bones poking out of stockpots, of puritan blandness and the unfashionably old-fashioned.” Swoon! You had me at “bones poking out.”

I’ll leave it to other Test Kitchen authors to write up dishes that are “delicious,” or “good.” I’m going for something else entirely – “English.”

Okay, that was a cheap shot. But let’s just say the target aesthetic here is more steampunk than “Top Chef.”

Kitchiner was a staunch pro-boiling partisan; he begins the “Rudiments of Cooking” section of his book with a chapter on it. His main points of advice are time-tested – skim the pot and keep it low and slow. He also shares data from his own experiments comparing the loss of mass for roasting (more) versus boiling (less, especially when the broth is reserved and used).

Kitchiner’s entry for Beef Bouilli (No. 5) is really more of a polemic in favor of boiling than it is a recipe. “Meat cooked in this manner,” he says

affords much more nourishment than it does dressed in the common way, is easy of digestion in proportion as it is tender, and an invigorating substantial diet, especially valuable to the Poor, whose laborious employments require support.

He continues in this vein, excoriating the poor for neglecting the “coarser cuts of meat” and choosing roasting over boiling, losing mass and nourishment in the process. Why, he wonders, can’t the miserable, hard-boiling, hard-drinking English be more like the French, who – despite having access to all the best booze – simmer and sip their way to perpetual good grace and humor?

When the pot begins to simmer, per Kitchiner’s instructions, I skim the top with a ladle, then add a quartered onion, two stalks of celery, a dozen berries each of black pepper and allspice, and a few sprigs of thyme. About four hours later, I remove the shank. I would say that I pull the meat off the bone, but more accurately it slides off onto the platter. At this point, I figure the shin bone has a few more hours of good boiling left in it, so I return it to the pot and let it go at a rolling pace for a while. The result is three quarts of rich, heady broth.

I’m sorry to report that I’ve completely failed in my efforts to turn the shin into a bland, dun-colored, flinty gnarl of meat. The beef I taste is flavorful, moist, and tender. Here’s my hot take on the Maillard reaction – it’s overrated.

Now it’s time to whip up the Wow Wow Sauce. I sample the mushroom catsup: liquid, salty, redolent of clove. It’s reminiscent of Worcestershire sauce, but in a different shape of bottle. The pickled walnuts are … unusual. The balsamic vinegar in which they’re packed dominates the initial touch on the palate, followed by traces of woodiness and tannin, like pine bark softened in mouthwash. Are they packed in the jars by smelly feet? I can’t say for sure. The texture is wet, crumbling clay.

Kitchiner’s Wow Wow recipe is fairly specific:

Chop some Parsley leaves very finely, quarter two or three pickled Cucumbers, or Walnuts, and divide them into small squares, and set them by ready; put into a saucepan a bit of Butter as big as an egg; when it is melted, stir to it a tablespoonful of fine Flour, and about half a pint of the Broth in which the Beef was boiled; add tablespoonful of made Mustard; let it simmer together till it is as thick as you wish it, put in the Parsley and Pickles to get warm, and pour it over the Beef, or rather send it up in a Sauce-tureen.

He then describes a series of optional ingredients one could add to make it more “piquante.”

Here’s a summary of what I ended up doing:

2 T chopped parsley

3 pickled walnuts, diced

2 T butter

1 T flour

1 c beef broth at room temperature

1 T vinegar from walnuts

1 T mushroom ketchup

1 t horseradish

2 T beer

Melt the butter in a pan over medium heat. Whisk in the flour and cook for 2 minutes, stirring frequently. Add the broth all at once, whisk into the roux, and allow the mixture to come to a simmer. Add the remaining ingredients except for the parsley and simmer for several minutes, until the sauce is thick and blended through. Finish with the parsley.

I spoon some of the sauce over the beef and serve it with mashed potatoes (No. 106) and green beans (No. 133, more or less). I’m usually someone who likes things, but to be honest, I’m not a fan of the Wow Wow Sauce. It’s essentially gravy with pickled walnuts, and since I don’t love the pickled walnuts, the gravy isn’t working for me. One Internet commenter refers to it as “basically adding all the strong stuff the Victorians might have found in their kitchen together,” and I think that sounds about right.

In the end, I mince the leftover meat, combine it with the stock, some vegetables, a splash of the mushroom catsup, and a cup of pearled barley, to make a substantial soup that – in the spirit of economy attested by Kitchiner – provides for lunches all week. This quality, the versatility of the boiled beef, is my main takeaway from my Test Kitchen endeavor, and it echoes in this proverb – with which I’ll conclude – quoted by the ever class-conscious doctor:

“Of all the Fowls of the Air, commend to me the SHIN OF BEEF, for there’s Marrow for the master, Meat for the mistress, Gristles for the servants, and Bones for the dog.”

1. Raleigh never came to Carolina, and in the interest of full disclosure, I didn’t visit the Rubenstein reading room until after I’d made the dish and drafted half this post. I did lay hands on the Fifth Edition in Duke’s collection. I also pulled out the single folder of Kitchiner manuscripts in the Trent Collection, and perused the five handwritten notes on social and mundane matters. But for the cooking activities of this project, and the quotations and references in this post, I made use of an Internet Archive version of the Fourth Edition, published in 1822.

Post contributed by Will Sexton, Head, Digital Projects and Production Services

The

The