Post contributed by Michelle Wolfson, Research Services Librarian for University Archives.

On my usual hunt for women in medicine, I came across a biography within the David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library entitled Nurse and Spy in the Union Army: Comprising the Adventures and Experiences of a Woman in Hospitals, Camps, and Battle-Fields. A nurse and a lady spy, too? I immediately requested the book.

I zipped around the book to get a sense of Emma Edmonds’s time during the Civil War. She was a nurse and when a need arose to infiltrate the Confederate army, Edmonds stepped up. Edmonds went through a process to test her abilities, and a line that stood out to me was regarding her phrenological examination—it showed that she was capable of being a spy.

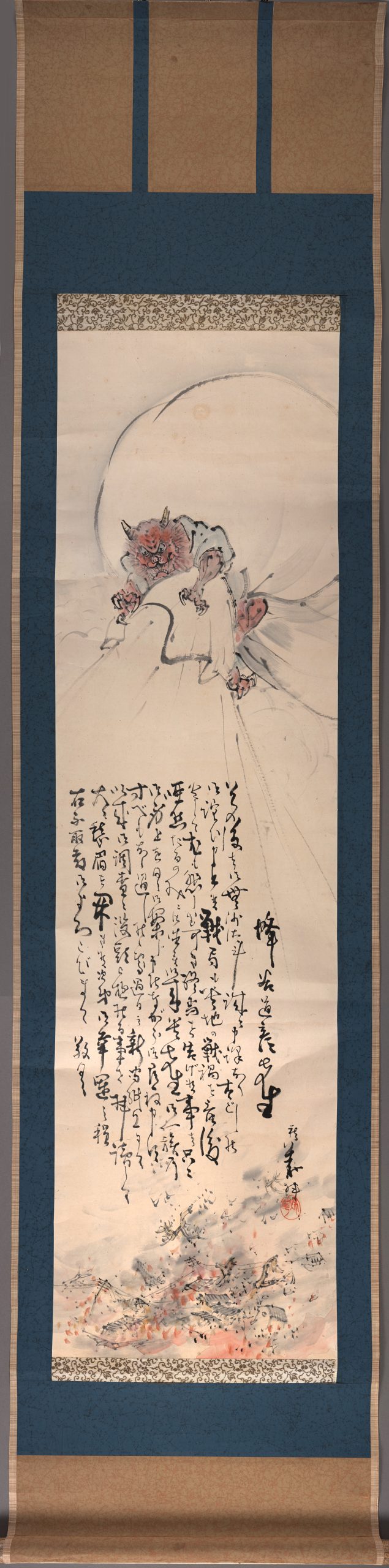

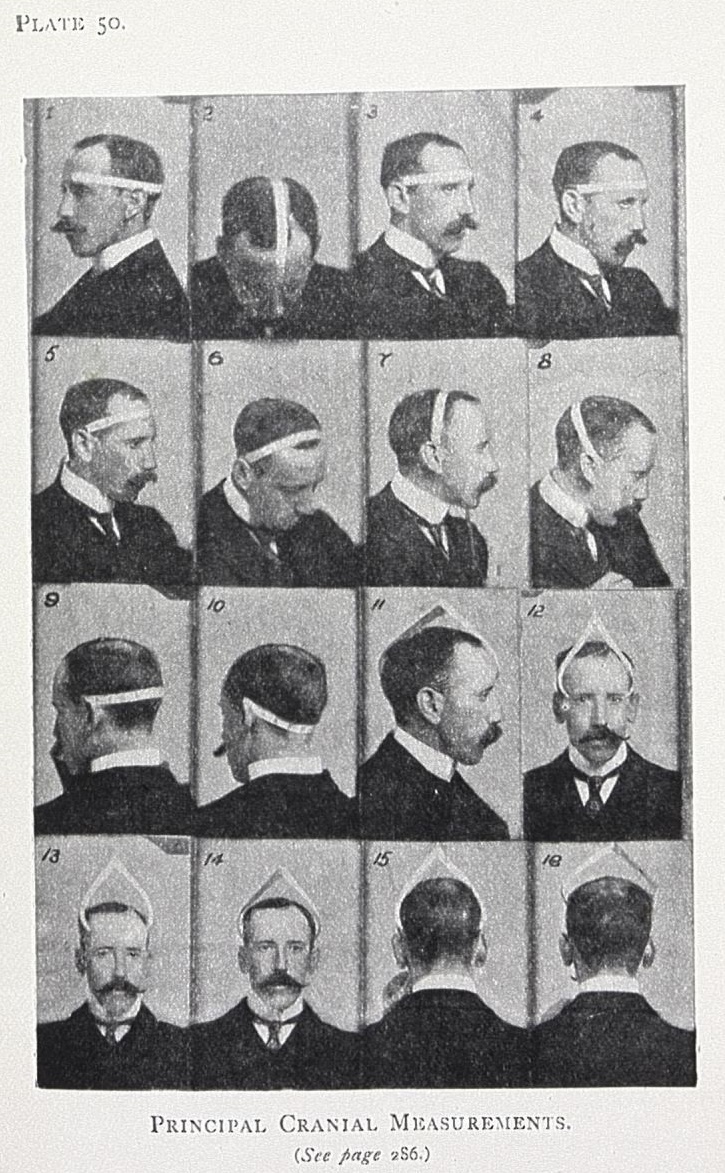

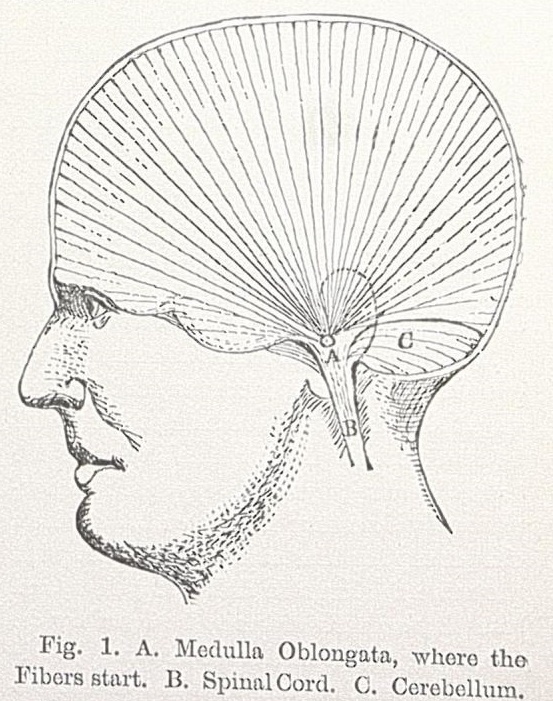

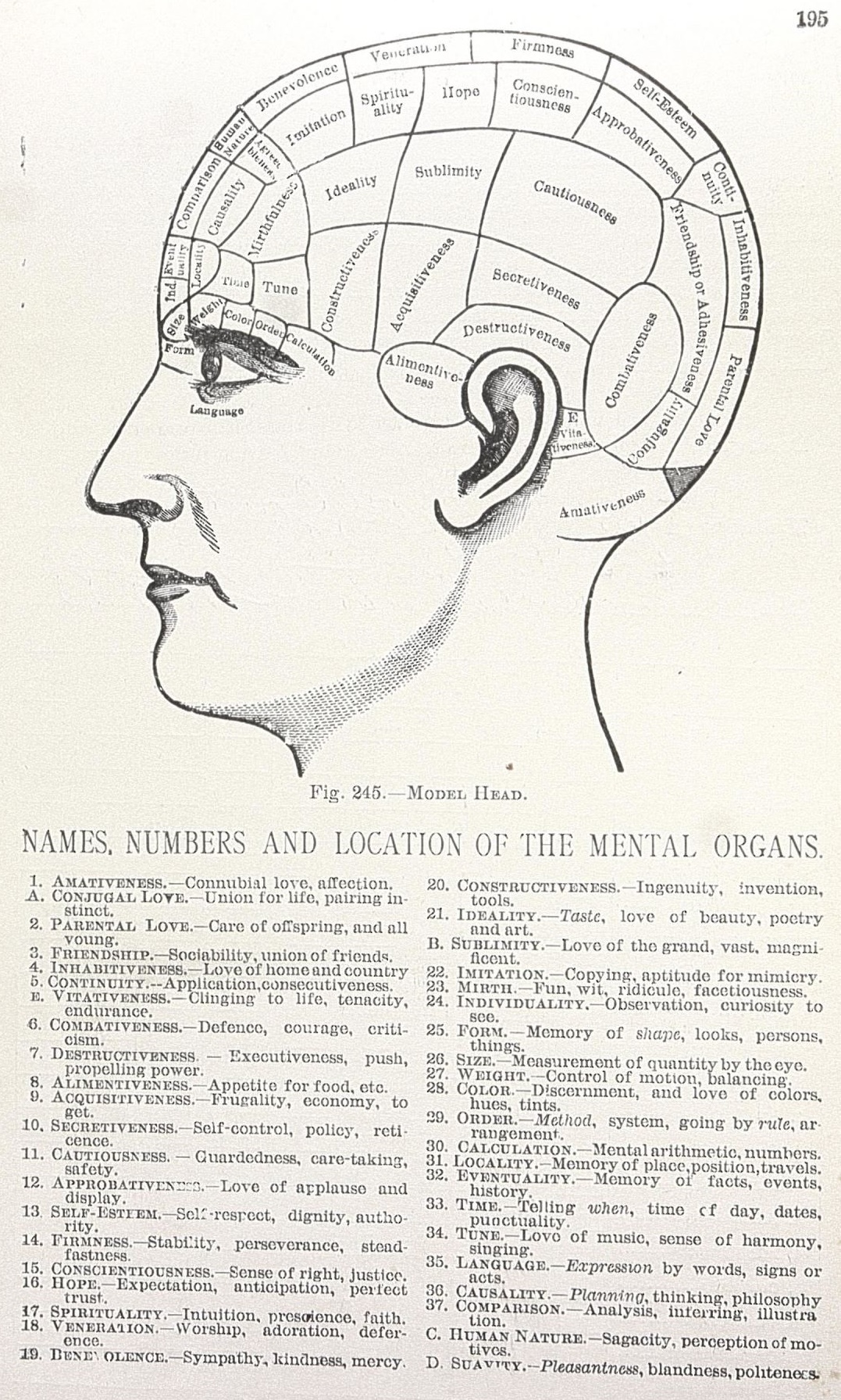

Phrenology has been covered here on the Devil’s Tale before, such as in this excellent post about the phrenology of the Dukes, and the History of Medicine collection includes several phrenological books to enlighten us further. To sum up, phrenology claimed to discern the strengths and weaknesses of a person’s character by measuring the distances from the top of their spinal cord (around the opening of the ear) to the surface of the head, with different characteristics assigned to different parts of the brain/regions of the head. Scientific Phrenology: Being a Practical Mental Science and Guide to Human Character, an Illustrated Textbook by Bernard Hollander, offers a guide on cranial measurements that one should start with their children at six months and go until the age of puberty.

People could participate in readings out of their own interest, to check their compatibility with a suitor, to aid in the raising of their children, and phrenologists also played a part in court cases. The pseudoscience’s popularity overlapped with the American Civil War, and apparently also guided in the hiring of spies.

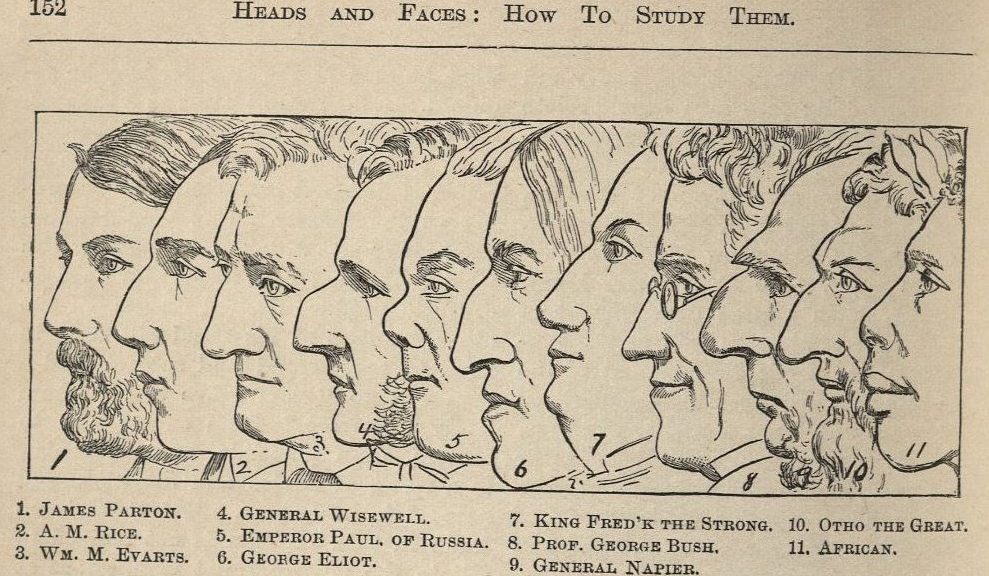

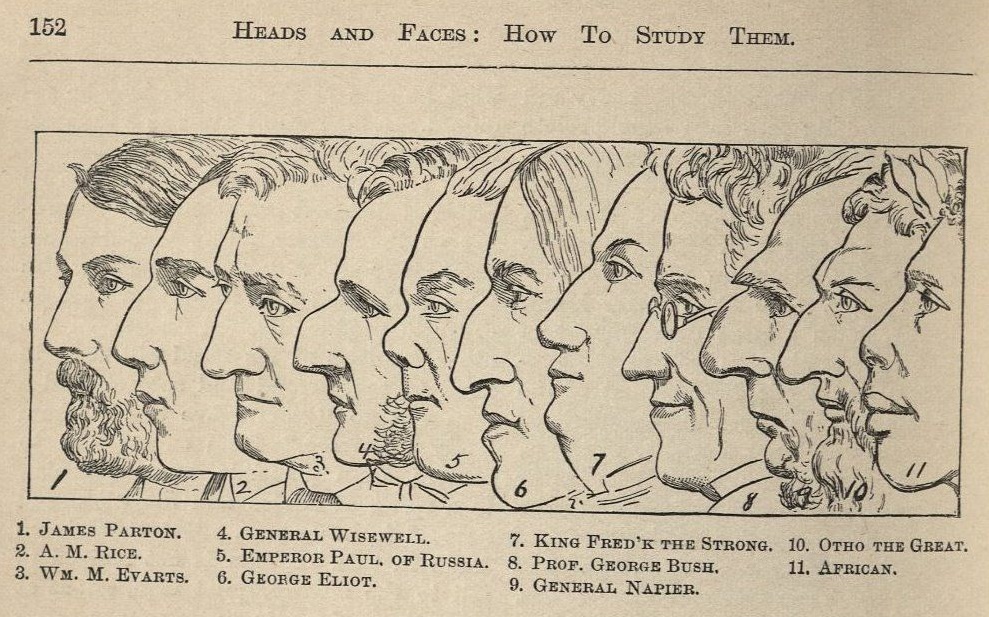

Heads and Faces, and How to Study Them, a Manual of Phrenology and Physiognomy for the People by Nelson Sizer and H.S. Drayton give us a breakdown of the characteristics phrenology covers.

Edmonds mentioned her phrenological exam found her organs of secretiveness and combativeness to be largely developed, then included a vague “etc.”. Regarding secretiveness and combativeness, Sizer and Drayton define it as:

- Combativeness. Meets duty bravely, has moral courage, intellectual enterprises, energy of character

- Secretiveness. They do not say or do anything in an open, frank manner, but it is by concealment, by artifice, and there is mystery in all they do

I then decided to make some guesses on what the “etc.” might include. If I were to guess at the qualities Edmonds was strong in (and I don’t mind guessing because this is quack science anyway, though my enthusiasm was tempered by the gross racism found rampant in phrenology and physiognomy), I would guess the following:

- Inhabitiveness. Love of home, patriotism;

- Self-esteem. Gives confidence in the exercise of courage and judgment;

- Firmness. Working with Combativeness, it produces determined bravery;

- Imitation. This attribute mostly calls for people to become more refined by imitating others, but it also refers to imitation in common modes of doing and acting;

- Individuality. Eager to see all that may be seen and nothing escapes their attention;

- Locality. Remembers where things or places are in respect to themselves; they will remember roads and places and directions in a town (here is where I would completely fail as a spy);

- Time. Remembers dates and times but also has a sense of time/how long things take; and

- Finally, I think Edmonds would have been low on Cautiousness, which can cloud over all manifestations, paralyzing courage, energy, determination, and Hope.

Lest we get too excited about lady nurses/spies and their exciting phrenological aspects, Scientific Phrenology reminds us that a woman like Edmonds is an exception, because as Hollander says, the average woman is less intellectual and more emotional than the average man “because of their mammary glands […], their sexual organs being concealed in the pelvis […]”, and various differences in their brains, such as their smaller frontal lobes.

Oh, phrenology, also a friend to misogyny.

This sort of reasoning is, of course, one of the reasons I seek out women in medicine, science, and life. And so we do not end on the sour note of misogyny, you can find meaningful resources on this LibGuide about women and their work in science and medicine.