Post contributed by Bennett Carpenter, John Hope Franklin Research Center Intern and PhD candidate in Literature

“Understand, sir, we are not asking for favors but as citizens of the United States and as members of her army we are asking redress for a wrong that has [been] so grievously and so flagrantly perpetrated against us. Yes we are her citizens but seemingly also present in the army of this great democracy are the forces that we might have seen in Nazi Germany when she was at her peak.”

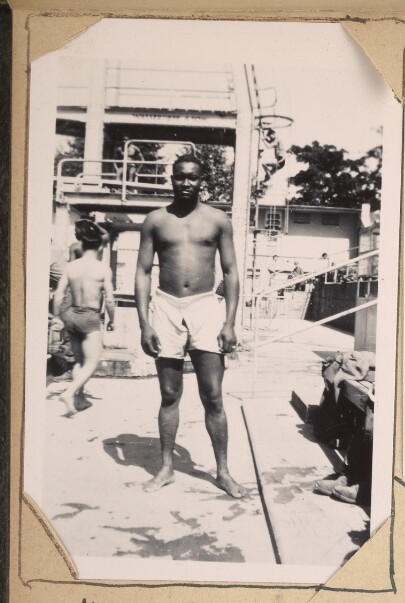

So wrote a group of African American soldiers to their commanding officer to complain about discriminatory practices barring them from using the swimming pool on their military base. Stationed in occupied Japan, the soldiers were tasked, they went on to note, with defending democracy against the threat of authoritarianism; yet it did not seem as if “democracy” always defended them.

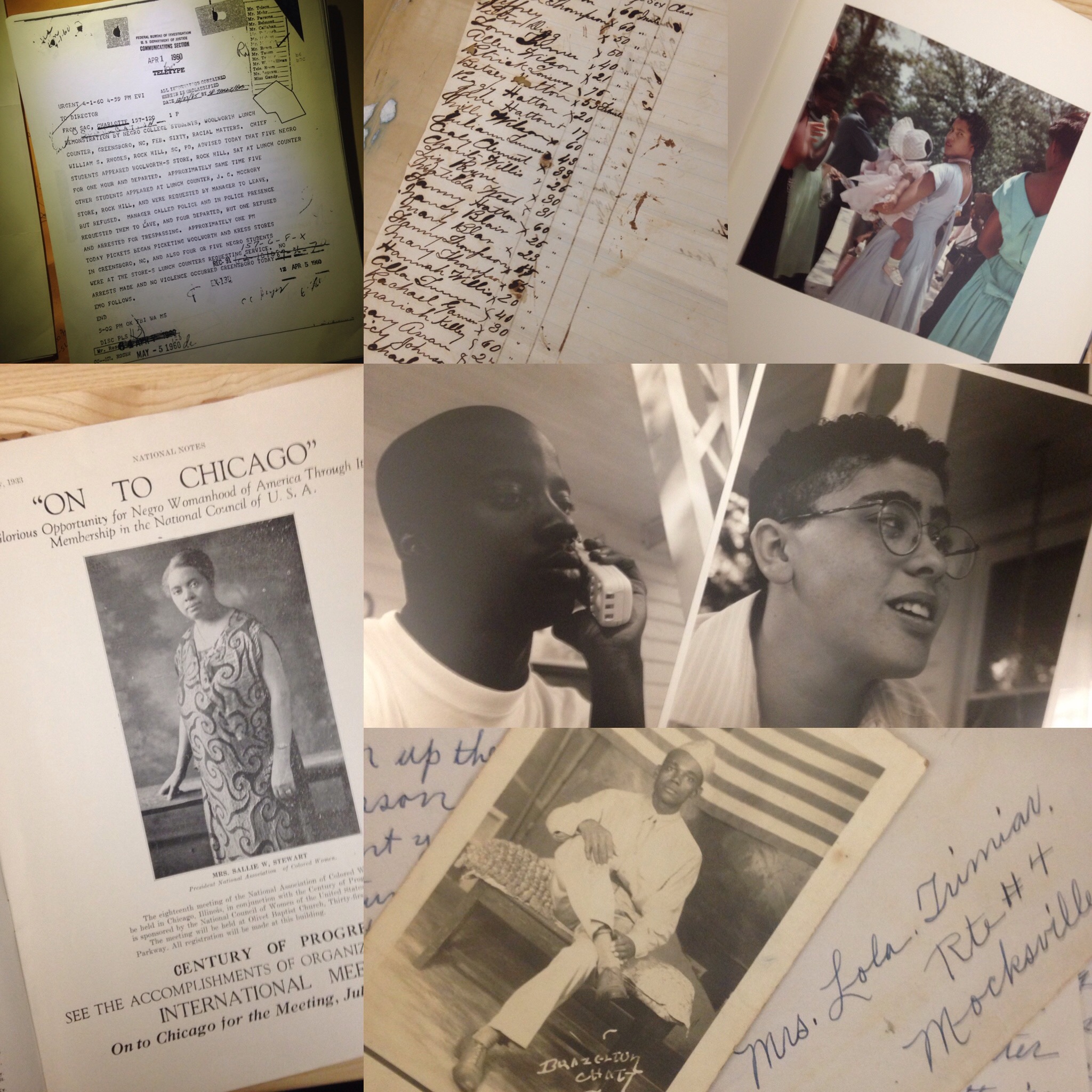

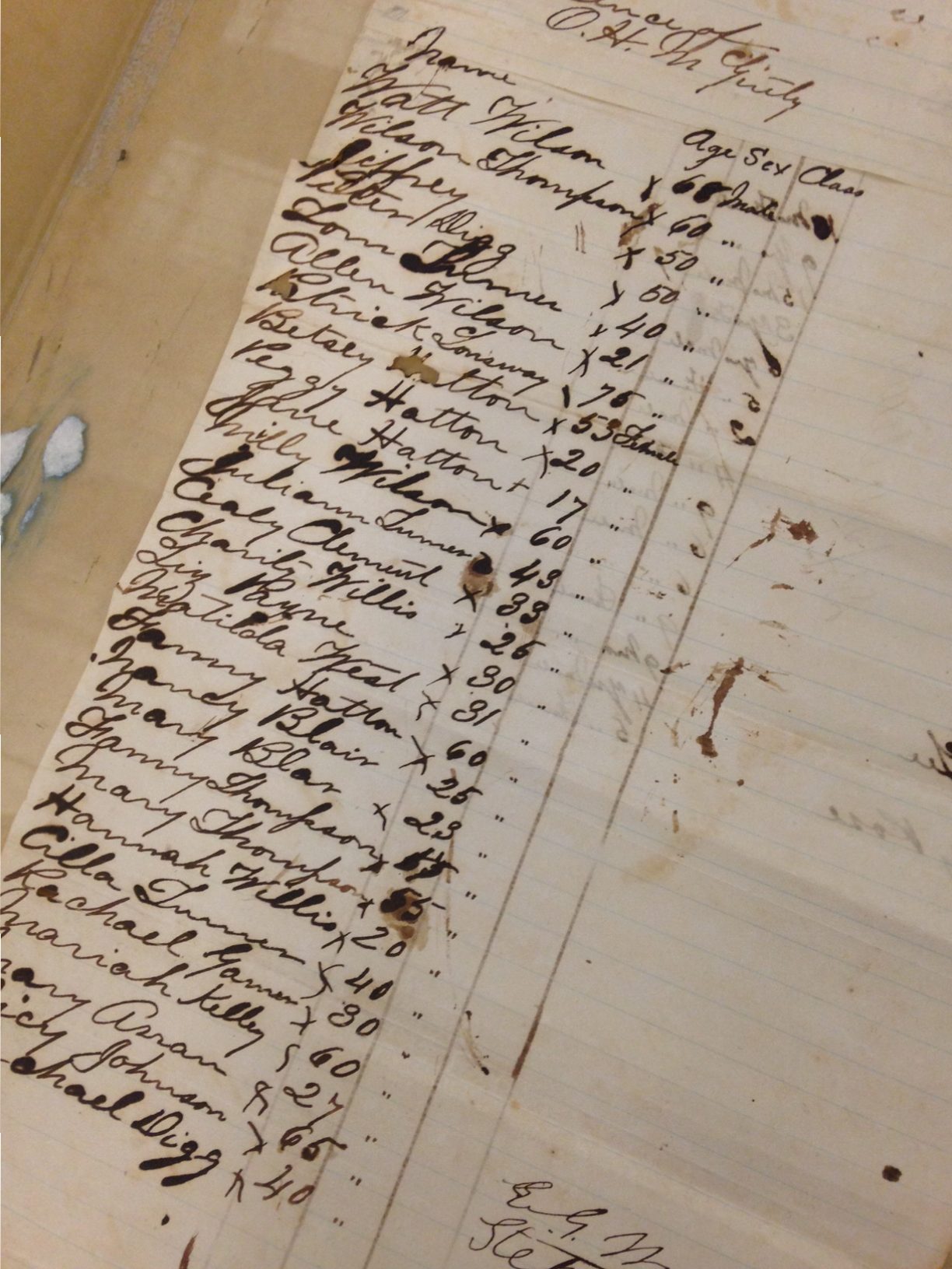

The letter, part of the Maynard Miller Photograph Album collection at the John Hope Franklin Research Center, helps document the complexity of the African American military experience. From the Revolutionary War through the present day, African Americans have fought and participated in every war in United States history. At times, military service offered African Americans opportunities for economic, professional and political advancement and escape from segregation and discrimination at home. At other times, however, racially discriminatory practices followed Black soldiers into service and denied them equal opportunities to advance, receive recognition and even to serve.

Now, with the digitization of the John Hope Franklin Research Center’s collection of African American Soldiers’ Photograph Albums, we can witness some of that complex history through the lens of Black soldiers themselves. The eight photograph albums in our holdings grant rich and fascinating insights into the African American military experience across several decades and continents.

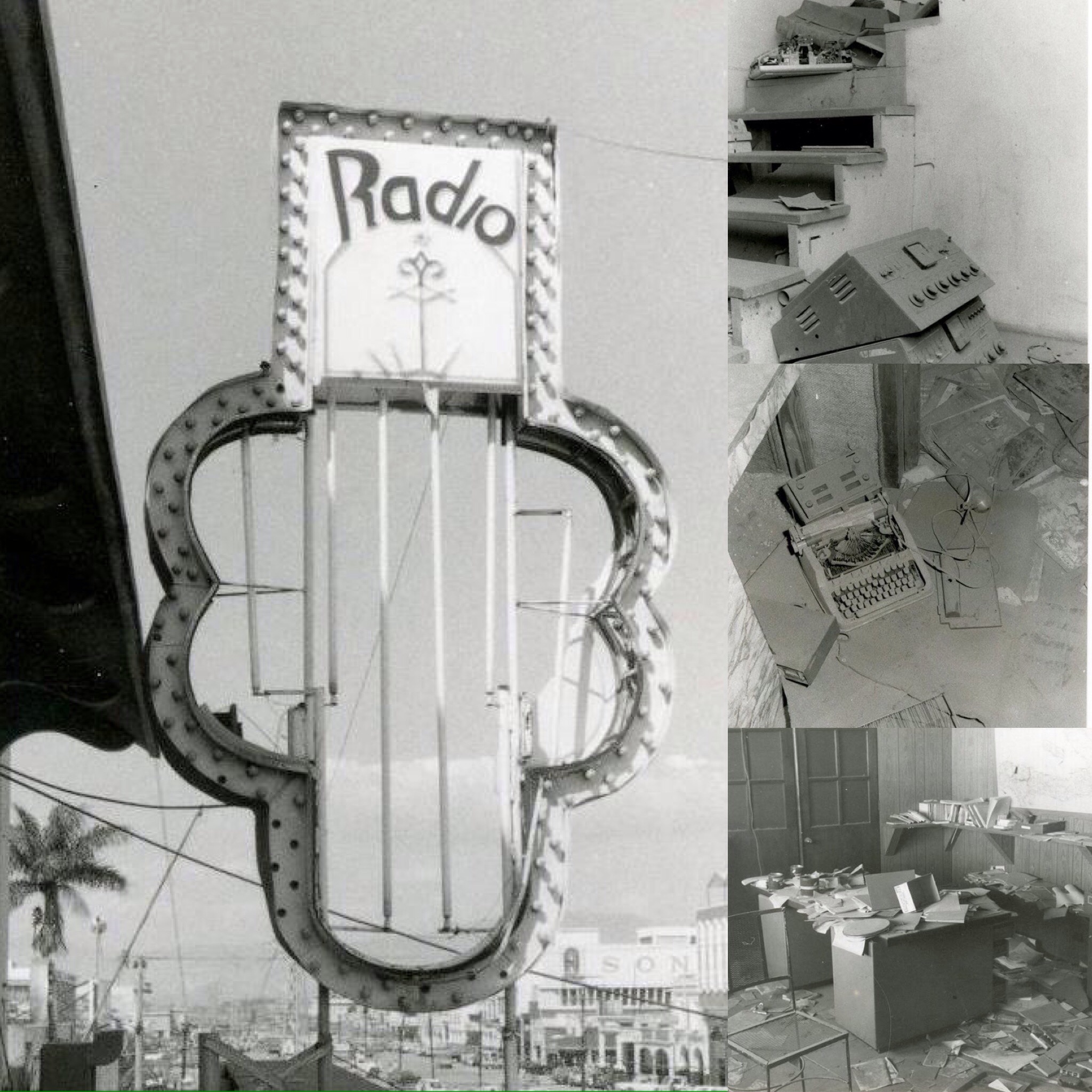

Along with the Maynard Miller Photograph Album, four other albums come from soldiers stationed abroad during World War Two. The Henry Heyliger Photograph Album likewise shows images of occupied Japan, while two other albums illustrate the experience of African-American soldiers in India and Italy. Finally, an album from Munich, Germany paints an interesting contrast with the discriminatory practices detailed by Miller, showing Black and white soldiers swimming together in an apparently unsegregated pool.

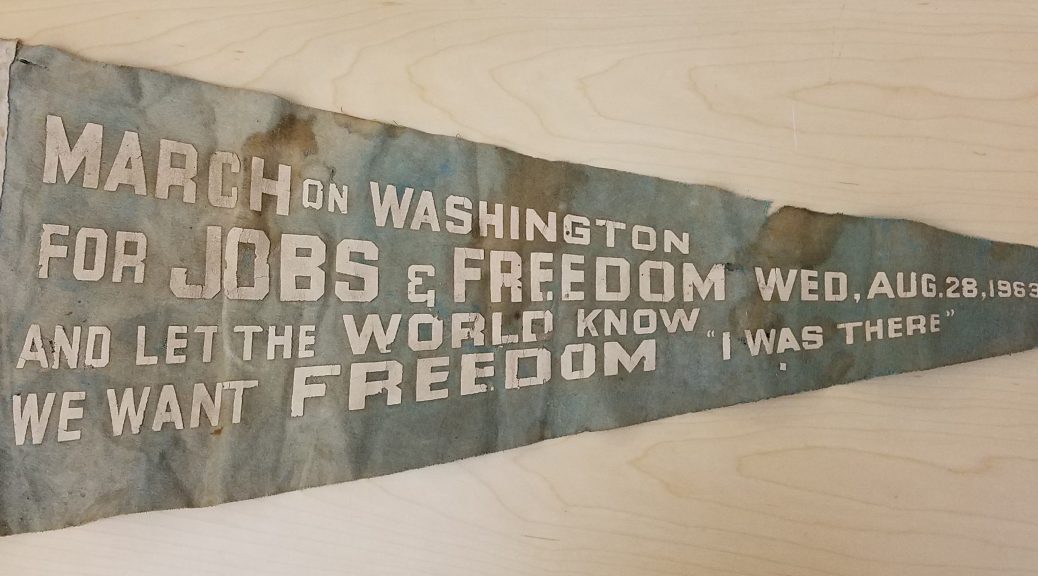

These contrasting experiences point to tectonic shifts in the Black military experience immediately before, during and after World War Two. Prior to the war, African Americans wishing to serve in the military had been largely restricted to support duties. In 1941, Black labor leader A. Philip Randolph threatened a mass march on Washington unless African Americans were granted equal opportunities, prompting President Franklin Roosevelt to lift racial restrictions on military service. While hundreds of thousands of Black soldiers subsequently served in the war, they were restricted to segregated units, such as the Tuskegee Airmen and the 761st Tank Battalion, popularly known as the Black Panthers. The armed forces would be ordered fully integrated by President Harry Truman in 1948, though the last segregated units persisted until 1954.

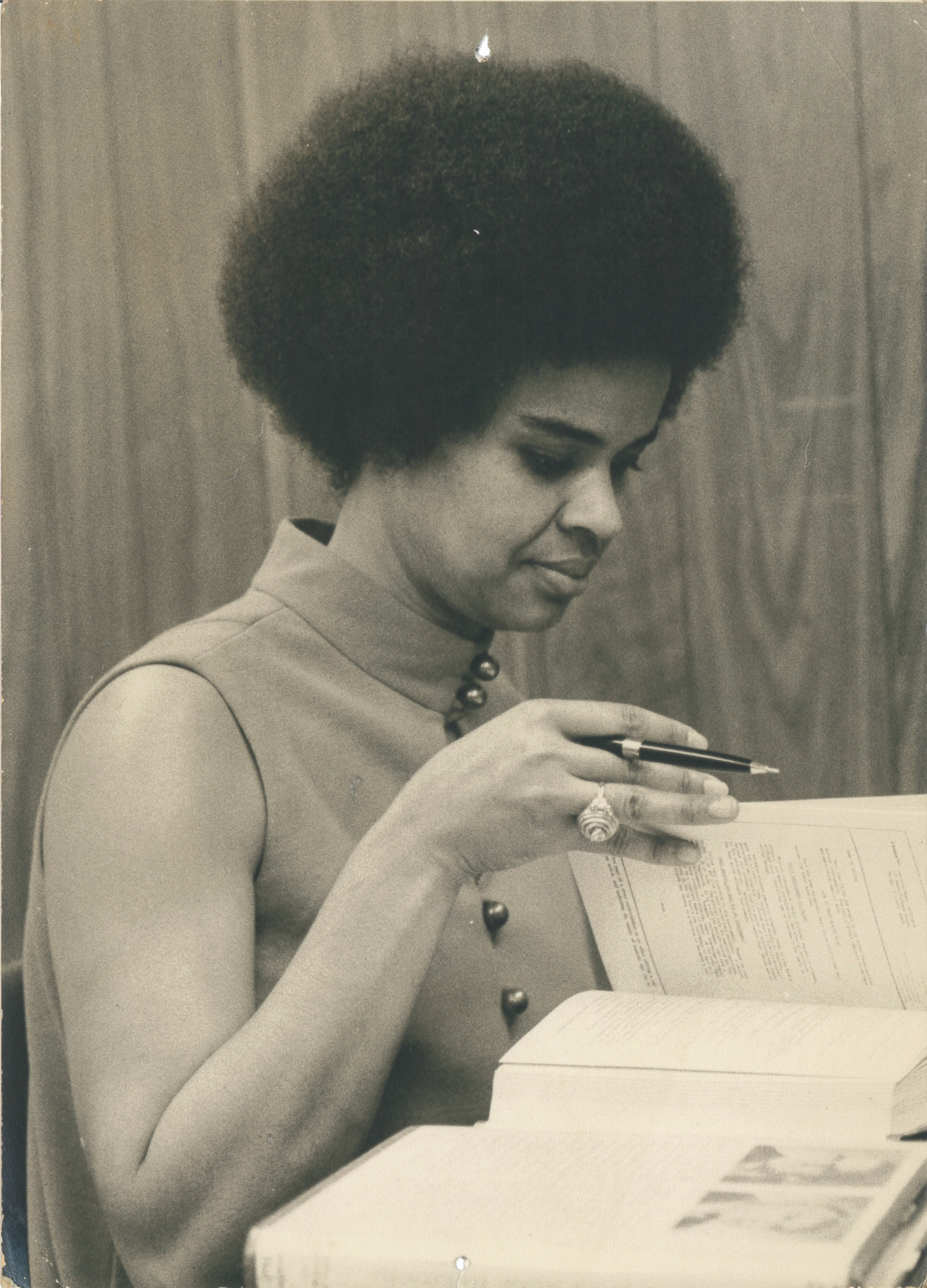

World War Two also led to another tectonic shift, as women other than nurses entered the American armed forces for the very first time. Our Women’s Army Corps Scrapbook includes fascinating early images of some of the very first women, both Black and white, to pass through the doors of the WAC Training School in Des Moines, Iowa. The second half of the scrapbook contains images of members of the 404th WAC band, the first and only all-women’s African American band in US military history.