We made it through week 1! Here are some sights spotted by our staff as we got down to work:

We made it through week 1! Here are some sights spotted by our staff as we got down to work:

One of John Hope Franklin’s most well known hobbies was growing orchids and he had a prized collection, which included over 1000 orchids of different varieties, shapes, and sizes. In 1959, while teaching in Hawaii, Franklin became fascinated with the precious flower.

Many of Franklin’s orchids were acquired during his travels around the world, and he built greenhouses in his homes in Brooklyn, Chicago, and Durham to cultivate and house his special collection of orchid specimens and hybrids. Franklin’s custom-built greenhouse at his home in Durham measured 17 x 25 feet.

In 1976, John T. Wilson, president of the University of Chicago named an orchid hybrid in honor of Franklin, the Phalaenopis John Hope Franklin. The flower, which is white and red in color, is recognized by Britain’s Royal Horticultural Society. Another species of orchid was named in honor of Aurelia Franklin after her passing in 1999.

The Franklin family was renowned for their orchid collection, and frequently showed them off to visitors to their home; John Hope frequently referred to them as his “babies.”

This series is a part of Duke University’s John Hope Franklin@100: Scholar, Activist, Citizen year-long celebration of the life and legacy of Dr. John Hope Franklin

Submitted by Gloria Ayee, Franklin Research Center Intern

The Hartman Center houses a Vertical Files collection from Brouillard Communications, a division of the J. Walter Thompson Company advertising agency, with files on an extensive set of industry groups and individual companies. While processing this collection I came across this 1948 ad for Avondale Mills of Alabama. The ad celebrates graduates from an Avondale Negro School with a quote from Booker T. Washington (“Cast down your bucket where you are”) and encouragement to take advantage of the opportunities that education provides, whether in one of Avondale’s mills—the ad points out that 1 in 12 Avondale employees were African American, about 600 out of the 7,000 total workforce—or in any of a number of other professions. As a corporate public relations piece, it is effusively inspirational.

We tend to think of Birmingham as the epicenter of the civil rights movement, a place Dr. King once called the most segregated city in America, where racial oppression was at its harshest. Bull Connor, the bombing of the 16th St. Baptist Church, King’s letter from jail there. History, however, is more complicated and more vexing. In 1897 Braxton Bragg Comer (who would serve as Governor of Alabama from 1907-1911) established a mill in the Avondale neighborhood of Birmingham, not far from the city center. Comer’s vision, carried out and expanded by his sons and other family members, was to create an ideal Progressive-era mill village, complete with schools, hospitals and dairy farms to serve the employees. Avondale employed men and women (and also some children, which brought sharp criticism from child labor reformers), white and black, and offered profit sharing and retirement plans, medical care, living wages, affordable housing, even access to vacation properties in Florida. By the time this ad ran in the Saturday Evening Post, the company had expanded to several mills and 7,000 employees who, as the ad proclaims “participate in Avondale’s ‘Partnership-with-People’.”

This all sounds very much like contemporary progressive economic and social rhetoric, and the list of Avondale’s employee benefits would be appealing today. The following decades, of course, would see the collapse of the textile industry in the U.S. South as production moved overseas (the Avondale Mills would themselves close for good in 2006), but here in this ad is a remarkable testimony to a social experiment that combined progressive social welfare ambitions with company town paternalism.

Post contributed by Richard J. Collier, Technical Services Archivist, John. W. Hartman Center.

If there is one truism about librarians it is that as a general rule, librarians are excellent cooks and bakers and they love to share their food. On the flip side, I’ve never seen food go to waste in a library. Your experimental cookie recipe didn’t turn out quite as you expected? Take them to work, someone will eat them.

If there is one truism about librarians it is that as a general rule, librarians are excellent cooks and bakers and they love to share their food. On the flip side, I’ve never seen food go to waste in a library. Your experimental cookie recipe didn’t turn out quite as you expected? Take them to work, someone will eat them.

This month, Amy McDonald and Beth Doyle of the Rubenstein Test Kitchen turn their attention inward to focus on our very own food culture. The recipes this month came from Duke University Recipes: A Collection of Recipes from the Duke University Community, Compiled by the Duke University Library Staff Association (DULSA). This cookbook, dated 1977, was one in a series of annual cookbooks compiled by DULSA.

Our first impression of the recipes in Duke University Recipes is that they are reminiscent of a particular type of independently-produced cookbooks (e.g. those created by churches, social clubs, member groups, etc.). If you are a fan of this genre of cookbooks you will recognize many of these recipes if not verbatim then by familiarity. They seem to be firmly situated in the culinary traditions of the 1970’s. The recipes often mix prepared food stuffs (so much Jell-O) with fresh (or “fresh”) foods to create something not quite from-scratch but better than from a box alone.

While there are many worthy entries in this cookbook, we wanted to pay homage to our colleagues by choosing three recipes submitted by Duke Libraries staff members who are still working at the library.

This recipe is one of those that is still popular today. It is usually called a “no bake cheesecake” or some variation of that theme. The recipe consists of a graham cracker crust, a cream cheese and whipped topping layer, and a Jell-O layer with canned fruit and orange sherbet added to the gelatin. When I asked Bob Byrd about this recipe he said, “I have only a vague memory of this recipe, and I disclaim all responsibility for it.”

The first two layers came together fine. The Jell-O layer was weird. It had so much liquid added to the Jell-O that it never really solidified, which was fine until it was served up. When cut and plated, the orange layer just slid off the base. But, as one taster said, “It all mixes in your stomach anyway.” True enough.

Taste-wise, it wasn’t half bad. The squishy Jell-O layer played nicely with the cream cheese layer. The graham cracker crust provided a textural contrast to the soft upper layers. In terms of preparation, I think if you omitted the sherbet the Jell-O would set properly and not be so messy to eat.

And, as a final note, one of our colleagues (who was born way after the 1970s) commented, “This tastes exactly like what I imagine the 1970s to have been like.” So there you go.

And, as a final note, one of our colleagues (who was born way after the 1970s) commented, “This tastes exactly like what I imagine the 1970s to have been like.” So there you go.

We were surprised at how many recipes in this book called for bourbon. We were pleasantly surprised we found one we wanted to try. According to Cathy Leonardi, “DULSA only served alcohol at one party each year, the Christmas party. The DULSA punch was the punch that was served. Wink was like 7-Up. The beauty of the punch was that it was easy to make. I didn’t invent the recipe. It was given to me by someone who had previously made it for the Christmas party. I put the recipe in the cookbook so that it would be easy to find for future parties.” And are we glad she did!

We were surprised at how many recipes in this book called for bourbon. We were pleasantly surprised we found one we wanted to try. According to Cathy Leonardi, “DULSA only served alcohol at one party each year, the Christmas party. The DULSA punch was the punch that was served. Wink was like 7-Up. The beauty of the punch was that it was easy to make. I didn’t invent the recipe. It was given to me by someone who had previously made it for the Christmas party. I put the recipe in the cookbook so that it would be easy to find for future parties.” And are we glad she did!

As far as punch recipes go, this is an easy one. The hardest part was finding the Wink soda (or is that pop?). Yes, Wink is still available but it is often found in the mixers section, not with the other sodas.

It mixes up to a beautiful reddish color. This is a very sweet punch with a little hint of Southern Comfort. Admittedly, we purchased the lower alcohol Southern Comfort since we planned on serving this at a reception at work. (We made a non-alcoholic version, too, but . . . that was less popular.) The general consensus was that it was the best thing on the table when we taste tested the recipes.

It mixes up to a beautiful reddish color. This is a very sweet punch with a little hint of Southern Comfort. Admittedly, we purchased the lower alcohol Southern Comfort since we planned on serving this at a reception at work. (We made a non-alcoholic version, too, but . . . that was less popular.) The general consensus was that it was the best thing on the table when we taste tested the recipes.

This is a pretty simple recipe. I started out with tons of strawberries and a store-bought crust (yesssss!). Half of the strawberries got sliced and dumped (or arranged prettily, if you prefer) into the baked crust, and the other half got mashed and cooked with the cornstarch and baking powder into what I like to fondly call the “strawberry goop.”

This is a pretty simple recipe. I started out with tons of strawberries and a store-bought crust (yesssss!). Half of the strawberries got sliced and dumped (or arranged prettily, if you prefer) into the baked crust, and the other half got mashed and cooked with the cornstarch and baking powder into what I like to fondly call the “strawberry goop.”

I have a tremendous fear of burning things, so I may not have let the strawberry goop cook—and thus thicken—quite as long as I should have. I poured it into the pie, let the whole thing set in the refrigerator, and the result was a sort of sweetened strawberry soup, with bits of crust. Not terrible, but maybe not what you want to serve at your next dinner party. Or maybe it is? You do you, you know?

As a saving grace, I was going to make real whipped cream, but Beth thought Reddi-wip would be more authentic. And archivists are nothing if not historically authentic.

Duke University Recipes is available through the Duke University Archives, as well as online at the Internet Archives. There is also a copy of this 1977 edition in the Perkins Library that you can check out.

Duke University Recipes is available through the Duke University Archives, as well as online at the Internet Archives. There is also a copy of this 1977 edition in the Perkins Library that you can check out.

Let us know in the comments if you try any of the recipes!

Post contributed by Beth Doyle, Leona B. Carpenter Senior Conservator and Head, Conservation Services Department, and Amy McDonald, Assistant University Archivist.

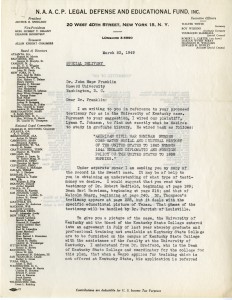

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), founded in 1909, is the oldest and largest civil rights organization in the United States.

In 1949, the NAACP approached John Hope Franklin to provide his expertise and testify at the Lyman Johnson v. University of Kentucky trial. The Johnson case successfully challenged the “separate but equal” doctrine that had been established by the Plessy v. Fergusson trial of 1896. John Hope Franklin later worked as the lead historian for the NAACP Legal Defense Fund team in preparation for Brown v. Board of Education in 1954. Franklin’s research contributed to Thurgood Marshall and the NAACP’s legal victory in this landmark case.

His relationship with the NAACP continued throughout his life, serving as a memeber of committees of the Legal Defense Fund and a mentor to a number of leaders in the organization. In 1995, the NAACP honored John Hope Franklin with the Spingarn Medal, “in recognition of an unrelenting quest for truth and the enlightenment of Western Civilization.” The Spingarn Medal is the NAACP’s highest honor, and is awarded annually to a person of African descent and American citizenship. The recipient of the Spingarn Medal is an individual who has attained high achievement and distinguished merit in any field.

This series is a part of Duke University’s John Hope Franklin@100: Scholar, Activist, Citizen year-long celebration of the life and legacy of Dr. John Hope Franklin

Submitted by Gloria Ayee, Franklin Research Center Intern

Mirror to America: The Autobiography of John Hope Franklin is a riveting memoir that chronicles Franklin’s life and offers a candid account of America’s complex history of civil rights the final book written by Franklin. Mirror to America was published in 2005 by Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

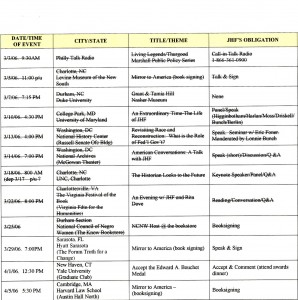

Franklin spent a number of years researching his own history, locating documents related to his family and his hometown, Rentiesville, Oklahoma. Once the book was completed, Franklin went on a national speaking tour, to not only share his personal story but discuss the impact of race in the many events he witnessed in American history.

In 2011, two years after Franklin’s death, Mirror to America received the Robert F. Kennedy Center for Justice and Human Rights Book Award. The RFK Book Award is presented to a novelist who “most faithfully and forcefully reflects Robert Kennedy’s purposes – his concern for the poor and the powerless, his struggle for honest and even-handed justice, his conviction that a decent society must assure all young people a fair chance, and his faith that a free democracy can act to remedy disparities of power and opportunity.”

This series is a part of Duke University’s John Hope Franklin@100: Scholar, Activist, Citizen year-long celebration of the life and legacy of Dr. John Hope Franklin

Submitted by Gloria Ayee, Franklin Research Center Intern

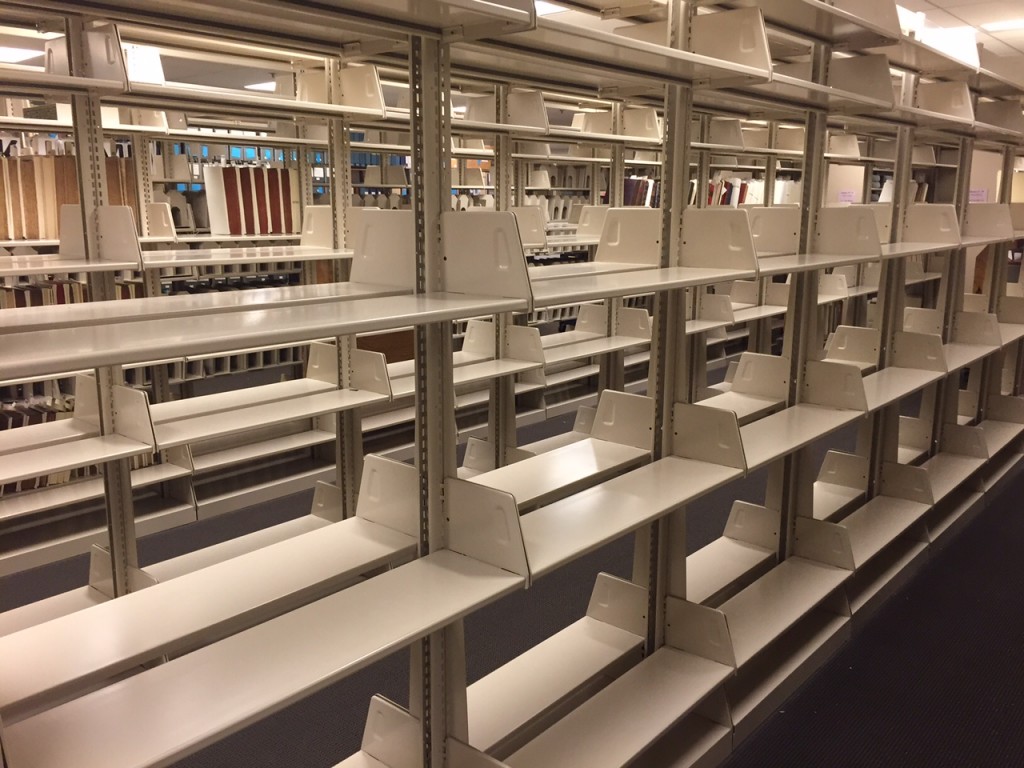

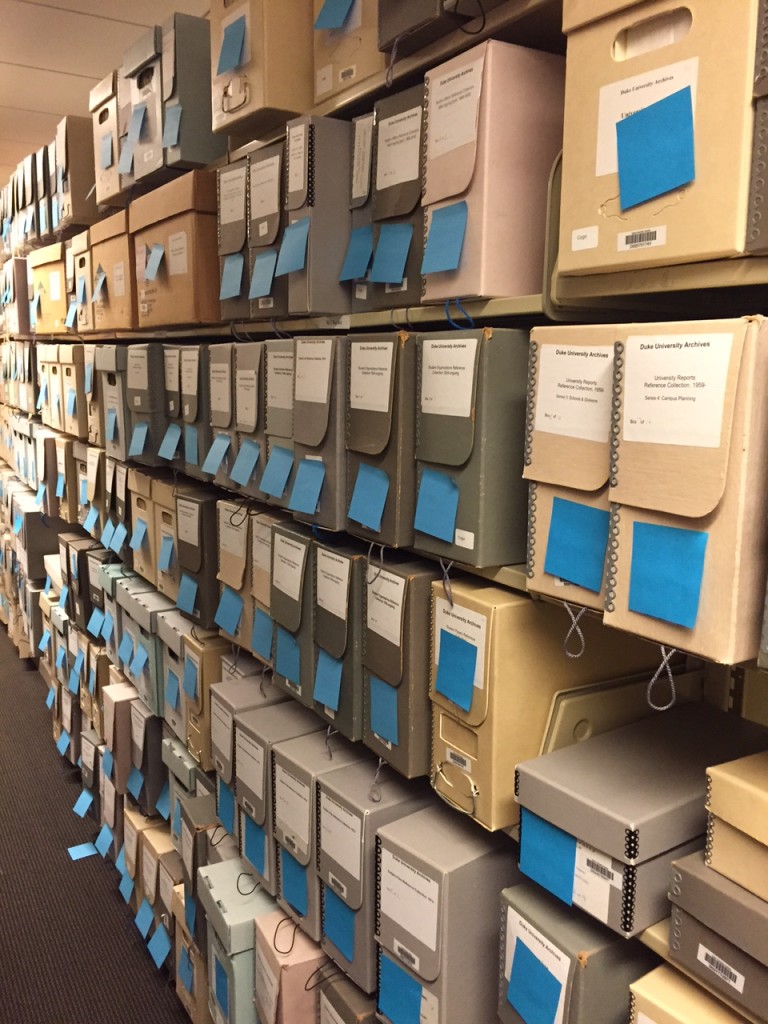

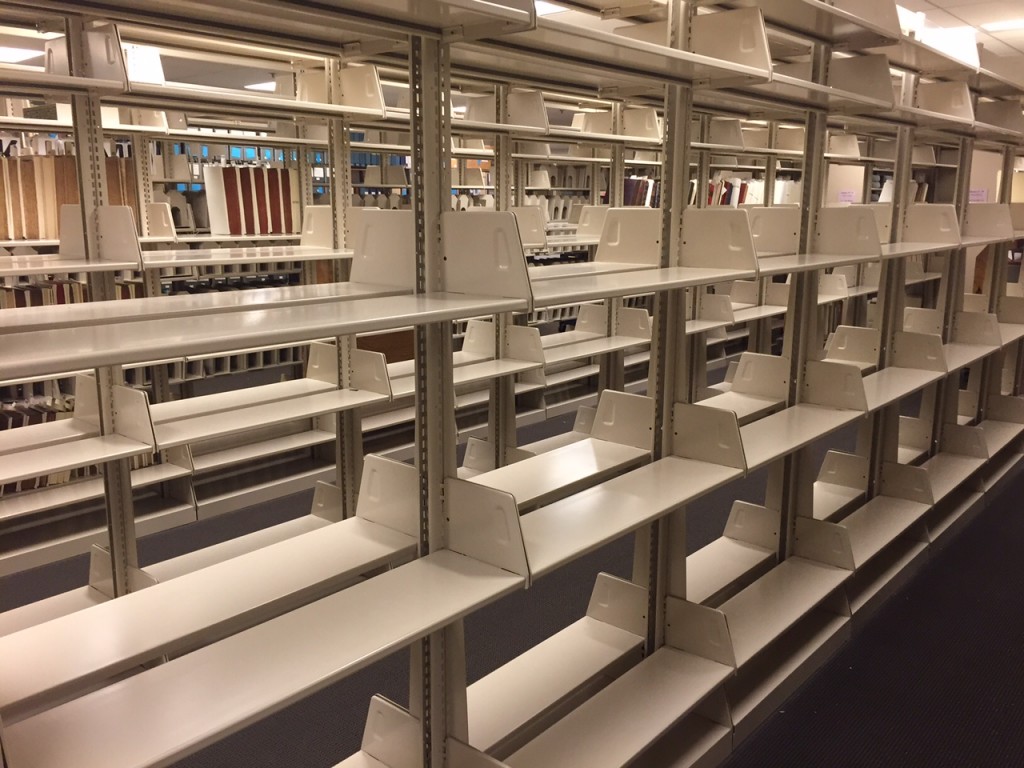

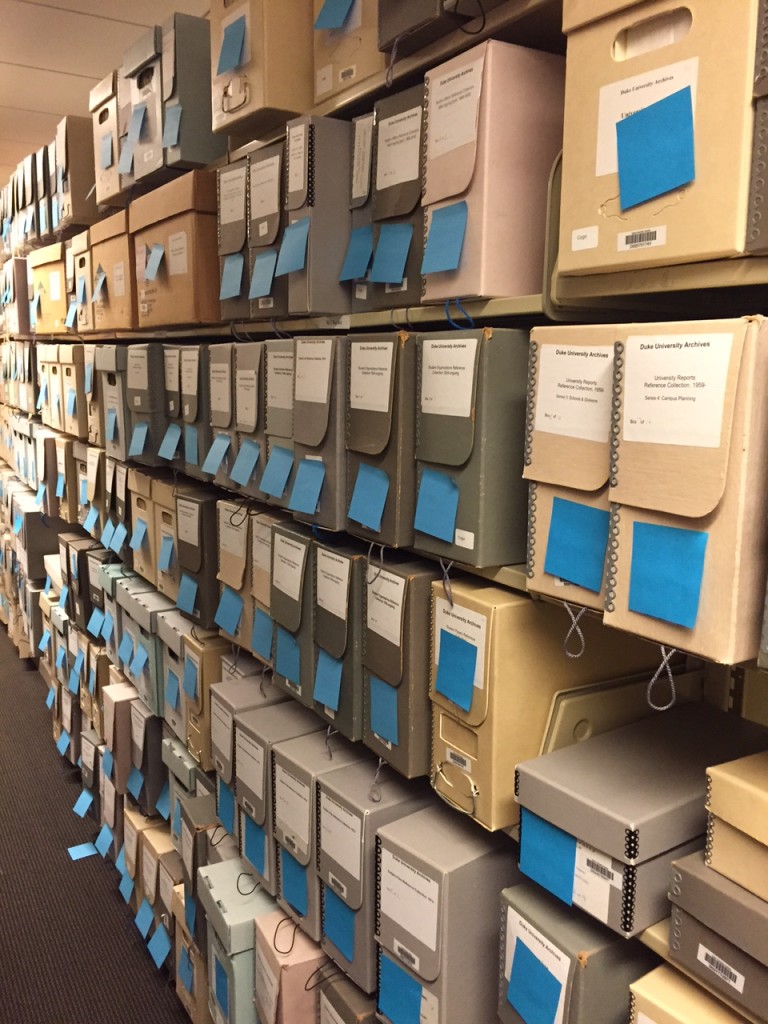

One of my most vivid memories of the Rubenstein Library is one of my first. Shortly after starting to work as a student assistant in the fall of 2011, I entered the dark, dusty labyrinth of the library’s old stacks and grabbed an item to reshelve. With great trepidation, I drew back both metal gates on the 1926 elevator, pushed the button for the fifth floor, and hoped that the creaky old machine would actually make it to our destination. Once I got out of the elevator and my pulse had returned to normal, I found the item’s home on the bottom of a row of shelves, set it back in its proper place, stood up, and found myself eye-to-label with the Stonewall Jackson Papers.

As a lifelong history nerd, I had known that I would enjoy working in the Rubenstein, but it was not until that moment that I realized exactly how cool the Rubenstein was, and what a great resource it is for the Duke community. That point was driven home even further when, as an undergraduate majoring in History and German, I used the Rubenstein frequently as a researcher. Knowing how important the Rubenstein is to researchers in a wide variety of fields made it all the more exciting to sign on as a Senior Move Assistant during the transition from our old space to the new.

In the two weeks since I started working full-time, I have been busy measuring volumes to help figure out where items are going to be stored in our new space, and “linking” bound-withs to help ensure that items which are physically bound together actually show up that way in the catalog. The move process is not simply moving items from point A to point B, and back to a refurbished point A. It is also an opportunity to improve and simplify many aspects of the library, and it is very exciting to be part of that process. Having worked and done research in both the old space and the temporary space, I can say that I am thrilled for the opening of the new Rubenstein Library. The move process is making a great campus resource even better, and I can’t wait to see the final result of the next few months of work!

Post contributed by Michael Kaelin (T ’15), Senior Move Assistant at the Rubenstein Library. Michael worked as a Student Assistant for four years. Originally from Wilton, CT, his interests include history and literature.

I was awarded a Mary Lily Research Grant in 2014 to travel to the Sallie Bingham Center for Women’s History and Culture to consult The Kathy Acker Papers. In April 2014 I carried out research in the archive for my book manuscript, Kathy Acker: Writing the Impossible, which is under contract with Edinburgh University Press.

Critics and scholars in the field of contemporary literature have largely understood Kathy Acker as a postmodern writer. My monograph challenges such readings of the writer and her works, paying close attention to the form of Acker’s experimental writings, as a means to position Acker and her work within a lineage of radical modernisms.

Consulting The Kathy Acker Papers, the extensive archive of Acker’s works housed at the Sallie Bingham Center, shaped my research in a number of ways. Most striking, and perhaps the aspect of the archive that has been most formative to my work, is what the archive revealed in terms of the materiality of Acker’s various manuscripts. The original manuscript of Acker’s early and most renowned work, Blood and Guts in High School (1978), is a lined notepad with text and image pasted onto the pages. It is a collage, an art object. The dream maps, which punctuate Blood and Guts in High School, are archived as separate framed objects. Dream Map Two is an artwork measuring 56 inches by 22 inches. Such archival discoveries enabled the development of my book. The monograph takes a specific work of Acker’s for each chapter as a means to explore six key experimental strategies in Acker’s oeuvre. A substantial knowledge of Acker’s avant-garde practices would not have been possible without the research carried out in the archive.

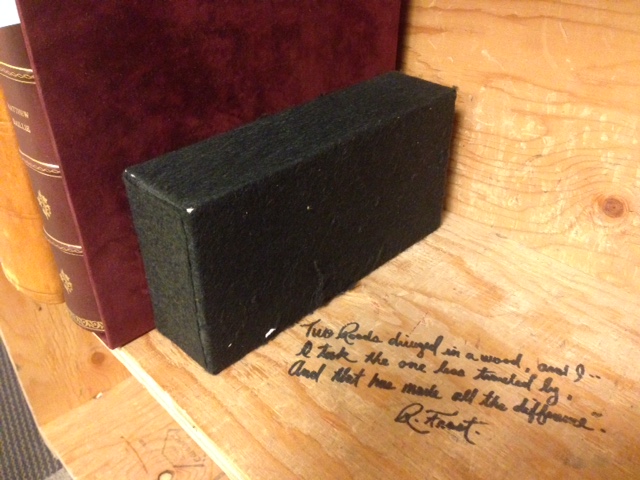

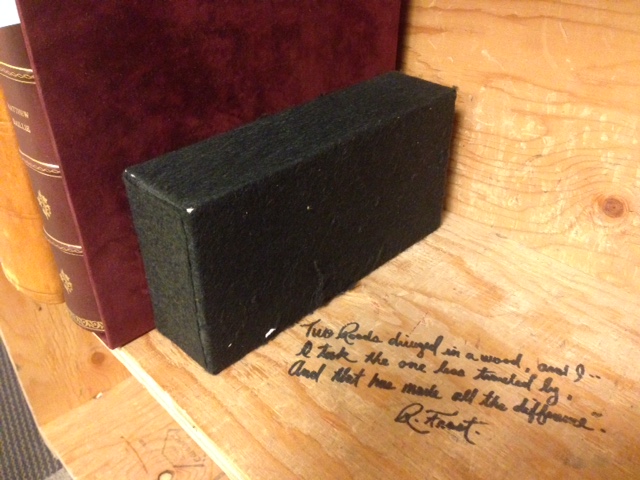

The Kathy Acker Papers also illuminated a related line of enquiry taken in my monograph: the importance of Acker’s early poetic practices to an understanding of her later prose experiments, which often dislimn the distinction between poetry and prose. The repository of unpublished poetic works provided rich material for the first chapter of my book, which explores Acker’s engagement with the L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E poets in the 1970s. Acker’s unpublished poetry can be understood as both a significant autonomous body of work, and as juvenilia that was a catalyst for her later writing experiments. The box that houses these early works also contains typed conversations between Acker and her early mentor, the poet David Antin. Written under Acker’s early pseudonym, The Black Tarantula, these conversations point to the discourses that emerged between Acker and various writers and poets concerning the uses of language. In this 1974 text, ‘Interview With David Antin’, which reads in part, and perhaps intentionally, like a Socratic dialogue, Acker and Antin interrogate issues of language and certainty. Acker and Antin draw on their writing experiments, alongside a discussion of Wittgenstein’s On Certainty, as means to interrogate language and perception. Such materials are rich when read in conjunction with Acker’s poetry.

Reading the materials in the archive, letters, early drafts of published works, speeches, Acker’s teaching notes and notebooks on philosophy, as well as Acker’s handwritten annotations on various texts, and her invaluable collection of small press pamphlets, was illuminating. Numerous texts disclosed the self-conscious nature of Acker’s experiments. A number of early poetic experiments are entitled ‘Writing Asymmetrically’, and several notebooks gesture specifically to the influence of William Burroughs and Acker’s experiments with the cut-up technique. Other notebooks are streams of consciousness, and are evidently comprised of material that Acker then cut up for use in her experimental works. Most of Acker’s novels originated this way, as a set of handwritten notebooks.

Archival research at the Sallie Bingham Center cultivated a rich understanding of the diversity of Acker’s experimental work and the writer’s remarkable lifetime achievements, many of which remain unpublished. The extent of the material and its uniqueness brought home the importance and centrality of the archive in the formation of knowledge regarding an experimental writer’s oeuvre. In the context of the female avant-garde writer, Acker stated that Gertrude Stein, as the progenitor of experimental women’s writing, is ‘the mother of us all.’ The remarkable experimentalism and the linguistic innovation of a great number of the texts that comprise The Kathy Acker Papers reveal Acker to succeed Stein as one of the most important experimental writers of the twentieth century.

Post contributed by Georgina Colby, Lecturer in Contemporary Literature, University of Westminster, UK.

Summer is gallivanting into Durham, and with it comes the promise of a new beginning for the Rubenstein, one involving fresh paint, new shelving, and a touch of tenacity. In a month, we’ll begin moving our materials and ourselves into our beautifully renovated home. Some Rubenstein spaces—like the Gothic Reading Room—will remain lovingly preserved, testaments to the memories that came before and to the new scholars who will soon discover them. Others will be similar in name only. I’m looking at you, Rubenstein stacks.

I’ve heard a lot about the pre-renovated Rubenstein stacks during my nearly two years here. The creaky elevators, the nooks, the crannies, the many doorways. These quirks are part of the collective Rubenstein conscious, and they’re spoken of fondly, frequently.

And while we’re sad to lose those charms, we’ve also been granted an opportunity to refine systems, to make materials more visible and easy to locate. We’ll no longer have a maze of classification schemes but one: Library of Congress. All of our print materials will be clustered by size: double elephants will chill next to double elephants; folios next to folios; mini materials next to mini. This is all great news for those of us lacking inner compasses. It also brings us to a logical question: how do we go about mapping locations for thousands of materials in this brave new world?

Easy! We turn to Tableau, a nifty data visualization service the lovely folks at Data Visualization introduced to us. Tableau allows subscribers to turn data into graphic representations that move far beyond bar graphs and pie charts—although it does have options for those as well.

Because we’re moving to a standard classification scheme, we now have more ways than ever to visualize our collections: we can look at overarching trends using the main classes of LC (e.g., “P” for Language and Literature or, “N” for Fine Arts); we can also get more granular than that. Within LC, there are subclasses that further delineate topics. PR—English Literature—is a subclass of Language and Literature, as is NA—Architecture—for Fine Arts. We can even delve deeper than that, looking at how many items are within a specific range of class numbers (e.g., PR1000-PR1100). With Tableau, we can then turn these data points into visual c(l)ues:

This visualization breaks out our print holdings first by size designation (12mo = duodecimo; 8vo = octavo; 4to = quarto), then by subclass. Looking at this, we know that we have substantial chunks of duodecimos classed in “B”—Philosophy, Psychology, Religion. We can also see that there are relatively fewer quartos and folios classed in Philosophy, Psychology, Religion. By doing this legwork, we know that we should probably leave extra space in the duodecimo section for materials classed “B.” Conversely, we also know that we won’t need to leave quite as much room in the folio areas for materials classed similarly.

Using a data visualization service has allowed us to be more accurate, more efficient, in our planning today so we won’t have to do as much shifting in the future. (Sorry wonderful colleagues! I can’t promise that we’ll never do shifting.) My own hope is that by doing this methodical (and methodological!) plotting today, the new stacks will be spoken of with the same fondness as the old stacks—albeit with less reverence toward crannies.

Anxiously awaiting our renovated space? It’s coming! From July 1st-August 23rd, the Rubenstein will be closed as we move into our permanent home. On August 24th, we’ll reopen to one and all.

Thanks to Mark Zupan and the Duke Libraries Renovation Flicker page for the excellent pictures; thanks also to Data Visualization for showing us its cool offerings!

Post contributed by Liz Adams, Collections Move Coordinator

The Meet Our Staff series features Q&A interviews with Rubenstein staff members about their work and lives.

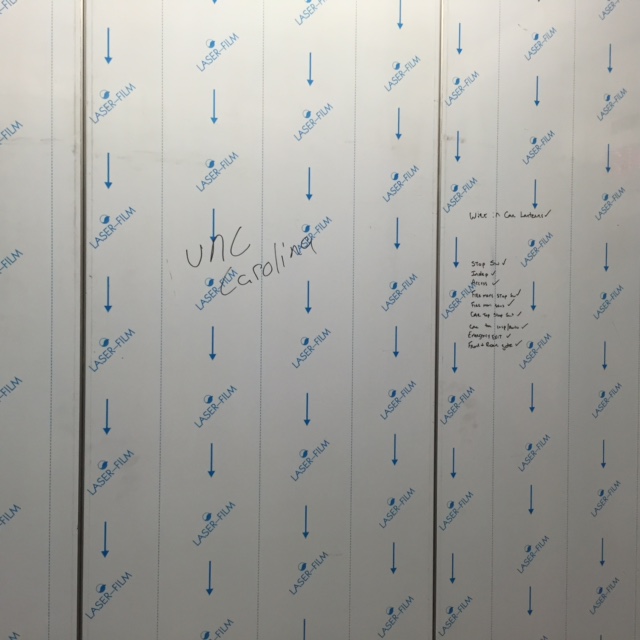

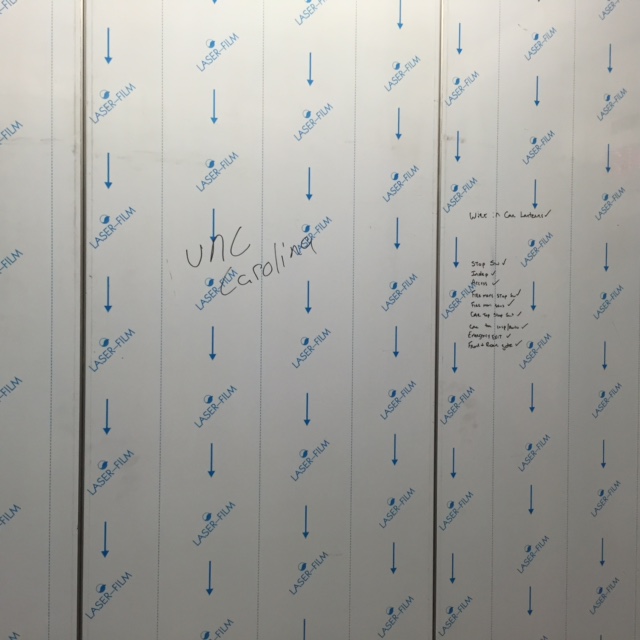

Craig Breaden joined the Rubenstein as our Audiovisual Archivist three years ago. Prior to his time at Duke, he spent seven years at the Russell Library at the University of Georgia. He has a BA and MA in history from Texas Christian University and Utah State University, respectively, and an MLS from UNC . He works on everything from small single-film collections to grant-funded preservation projects involving thousands of audiovisual items. He facilitates preservation work, provides access to obsolete formats, processes (inventory and catalog) collections, and functions as the go-to oral history guy.

Tell us about your academic background and interests.

I started out interested in frontier history particularly, and how popular images of the American West inform the way Americans think about themselves, their creation myths, the rest of the world. I’ve also had a lifelong love of music and a fascination with recorded audio and video. Our audiovisual heritage provides a different, animated view of the past, and can carry a unique emotional weight.

What led you to working in libraries?

I’d had some experience working in a special collections library while in college, but it took a long while for me to come to the profession. Some folks are late bloomers, I guess. After years of working in corporate atmospheres unrelated to my academic background, I’d come to the point where I wanted to start making a difference and make a living. It was the idea that work should mean something, make some kind of contribution to the society as a whole. There are of course all kinds of ways to do this, but I thought I should play to my strengths. I had a challenging and satisfying year of teaching 8th grade social studies, but knew that I could give more outside the classroom by focusing on what we might consider the raw materials of educators, those cultural heritage resources that give voice to the past. It so happened that one of the best library schools in the country (UNC-Chapel Hill) was just down the road, and I applied and fortunately got in. I decided to focus on my background and my interest in A/V, and while in school pursued audiovisual archiving as an emphasis of my library education. I owe a big debt to the Southern Folklife Collection and its director, Steve Weiss, in helping me on my way, and to the great librarians at the University of Georgia for giving me a shot.

How do you describe what you do to people you meet at a party? To fellow librarians and library staff?

I usually tell people I’m an archivist in Duke Special Collections. Sometimes that leads to further conversation, other times not. I think in general there’s a real disconnect, a misunderstanding about what history really is. It’s hard to say to most people that what we think of as history is what it is because of what we do in libraries and archives like the one here at Duke. Colleagues get it, but I think usually the best introduction for them is when they get a CD or tape or film as part of a collection and wonder, at the very basic level, what to do with it.

What does an average day look like for you?

One of the great things about my job is that there aren’t many average days, but most days hold some combination of digital preservation, inventorying collections, answering reference questions via email, figuring out how to run a film or a video or audio tape so that we know what’s on it, and advising colleagues on portions of their collections that hold AV. Then there are often questions related to policy creation and the changing landscape of digital preservation. And let’s not forget the meetings….

What do you like best about your job?

I like figuring out problems that fall into my domain of expertise. I do a ton of troubleshooting and tinkering to get AV to simply play back in a way that it can be accessed, and these nuts-and-bolts successes are always satisfying and really essential to what I do. I also enjoy meeting donors and getting to know the personalities behind the stuff, just as it’s always great to help a researcher plug into something they might not have been aware of. And of course my colleagues – every one of them brilliant in completely different ways.

What might people find surprising about your job?

The amount of time spent with spreadsheets and on email. The first is part and parcel of what we do, that is, knowing what we have, the second is all about attempting to efficiently communicate (jury’s out on that, though). Pleasantly surprising is that amazingly smart colleagues have something interesting to show or talk about every day. Archives can be mind-blowing.

Do you have a favorite piece or collection at The Rubenstein? Why?

The H. Lee Waters Films for their big heart, the Frank Clyde Brown field recordings for all the secrets they hold in their wax cylinder and lacquer disc grooves (and that will soon be secret no longer), the home movie collections we have that tell a story beyond what’s happening onscreen, and all the fragile and forgotten bits of film and video that share our shelves equally and continue to have a voice.

Where can you be found when you’re not working?

With my kids, cooking, strumming a guitar (sometimes all three at once).

What book is on your nightstand/in your carryall right now?

The Buried Giant by Kazuo Ishiguro; The Innkeeper’s Song by Peter S. Beagle; Hold Tight, Don’t Let Go by Laura Wagner; and Haiti: The Aftershocks of History by Laurent Dubois.

Interview conducted and edited by Katrina Martin.