This is a food story that begins in a laboratory. Imagine white coats, goggles, beakers, hastily written formulas on a chalk board, and vapors with odd odors. No, this is not the kitchen-lab of a trendy restaurant specializing in molecular gastronomy. This is a lab at the Kraft Cheese Company and the year is 1915. This is the beginning of Velveeta.

This is a food story that begins in a laboratory. Imagine white coats, goggles, beakers, hastily written formulas on a chalk board, and vapors with odd odors. No, this is not the kitchen-lab of a trendy restaurant specializing in molecular gastronomy. This is a lab at the Kraft Cheese Company and the year is 1915. This is the beginning of Velveeta.

According to a 1930 advertisement from Kraft’s Educational Department titled “The Story Behind the Product,” in the year 1915, Kraft research scientists, uncomfortable with the amount of valuable milk nutrients lost in the traditional cheese making process, embarked on a food quest: to create a cheese product that would retain all of these nutrients without losing all of the desirable characteristics of ordinary cheese. Ladies and gentlemen, the results of that noble inspiration are, in my mind, truly a food miracle. Named for its smooth, velvety texture when melted, Velveeta is a dairy-based product composed of cheddar cheese, whey concentrate, skim milk solids, cream, sodium phosphate, and salt (the 1930 ingredients list). But how would the company sell this miracle cheese food to American consumers? How would they transform this product from a science experiment to a staple of the American table? This would be a task assigned to Kraft’s advertising agency of record, the J. Walter Thompson Co. (JWT).

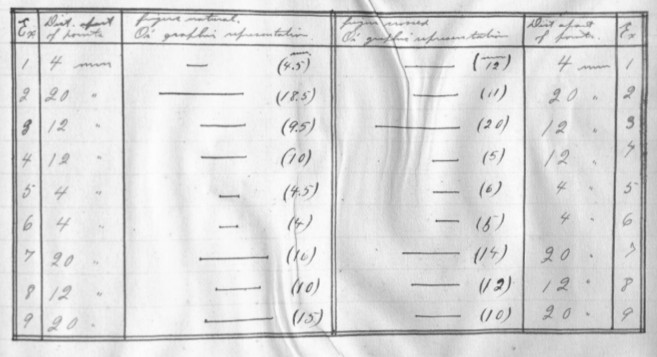

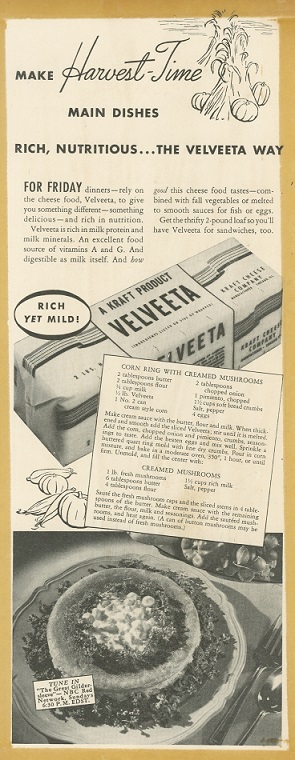

With slogans such as “Let Them Eat it Freely!” and “As Digestible as Milk Itself!,” Velveeta’s early advertisements were educational with a focus on the product’s nutritional benefits, particularly for growing children. A 1932 advertisement that appeared in several women’s magazines boasted of the product’s endorsement by the Food Committee of the American Medical Association and its award of a nutritional rating of “Triple-Plus.” Velveeta’s balance of vitamins and minerals would effectively build up “resistance to colds, throat and lung infections,” act as a “safeguard against unsound teeth and bones,” and contribute to the “building of firm flesh.” With Velveeta’s nutritiousness established, by the mid-1930s JWT’s campaigns for Velveeta began to focus on the product’s versatility in the kitchen.

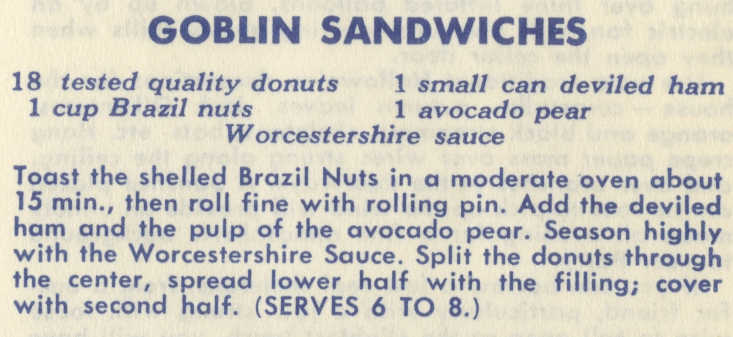

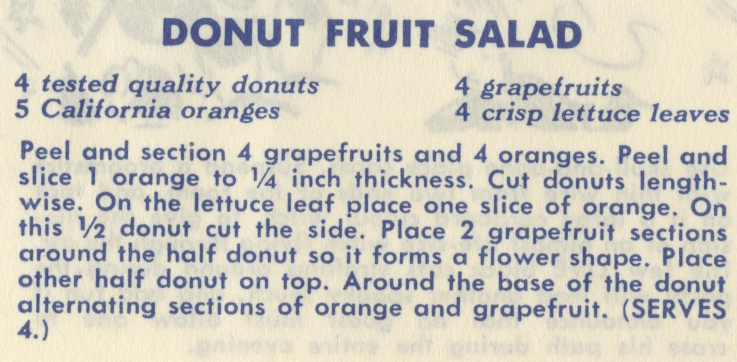

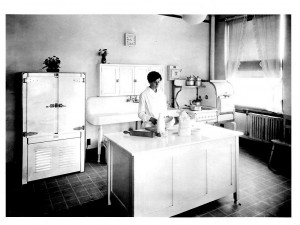

In order to instruct American consumers on the myriad culinary uses of Velveeta JWT began to introduce recipes in the advertisements, a practice pioneered by the agency in the 1910s for another Chicago-based food client, Libby, McNeil & Libby. In 1918, JWT opened a test kitchen in its Chicago office in part to develop recipes that featured their client’s products as central ingredients. It was in this kitchen that JWT developed hundreds of recipes incorporating not just Velveeta but many other clients’ brands. As the home of the Archives of the J. Walter Thompson Co. the Rubenstein Library has hundreds if not thousands of these advertisements.

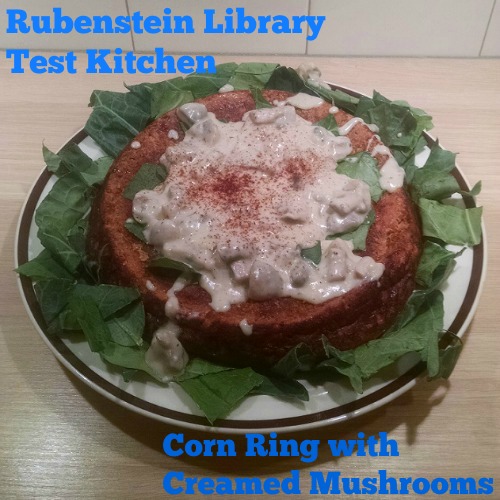

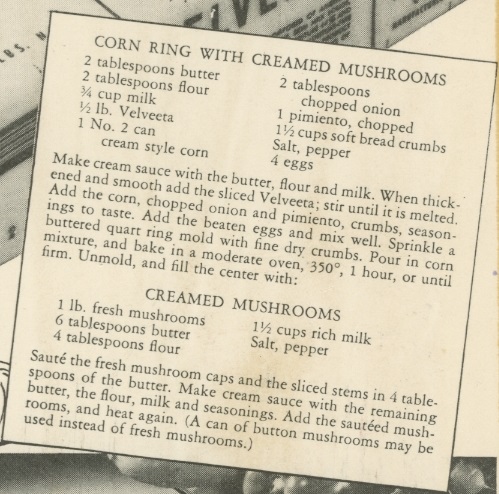

My obvious enthusiasm for Velveeta aside, I chose this recipe for a harvest-time corn ring with creamed mushroom sauce for several reasons. First of all, despite the fact that the recipe is devoid of any harvest fresh ingredients, the fall harvest theme seemed appropriate for this time of year. Secondly, mushrooms. I also wanted to see what this thing looked like in color—I had a feeling the black and white photo wasn’t doing the dish any justice. Lastly, with winter approaching I felt myself in need of some firm flesh building, one of the many benefits of a steady Velveeta diet.

I more or less stuck to the recipe in the ad with only slight modifications. I at least tripled the amount of diced onion, added a pinch of paprika to the corn ring batter, and used crushed croutons rather than fresh bread crumbs. Additionally, despite the fact that everything from our grandparent’s kitchens is now trendy again, I do not possess a ring mold. To mimic a ring mold I used an upside-down glass ramekin in the middle of a 9-inch pie pan. Although this rig lacked the authenticity of a 1940s ring mold I felt it to be sufficient. I also opted against the recommendation of the recipe that I purchase the economical 2lb. loaf of Velveeta, opting instead for the 16oz. package. Other than dicing the onion and quartering the mushrooms there was minimal prep.

The corn ring actually smelled wonderful while baking, filling the house with a warm cheesy aroma. After plating the corn ring with the mushroom sauce I began to understand why they opted for a black and white photo in the ad. Aside from the decorative greens, the brown and grey color palette of the dish wasn’t exactly photogenic so I sprinkled a dash of paprika on top to give it a bit of color. There were also no serving instructions so we sliced it like a pie and watched the creamy mushroom sauce flow. Although extremely rich the dish was actually quite good overall. This is one instance at least where the product lives up to the promise of the ad.

Every Friday between now and Thanksgiving, we’ll be sharing a recipe from our collections that one of our staff members has found, prepared, and tasted. We’re excited to bring these recipes out of their archival boxes and into our kitchens (metaphorically, of course!), and we hope you’ll find some historical inspiration for your own Thanksgiving.

Post contributed by Josh Larkin Rowley, Reference Archivist, John W. Hartman Center for Sales, Advertising, and Marketing History