Keeping it together can be a real challenge these days. There are many effective strategies for maintaining one’s mental health, but unfortunately this blog post isn’t about any of that. This blog is about library and archives materials. So I’m here to share a simple system for keeping it together when you are working on a textblock in need of some major intervention.

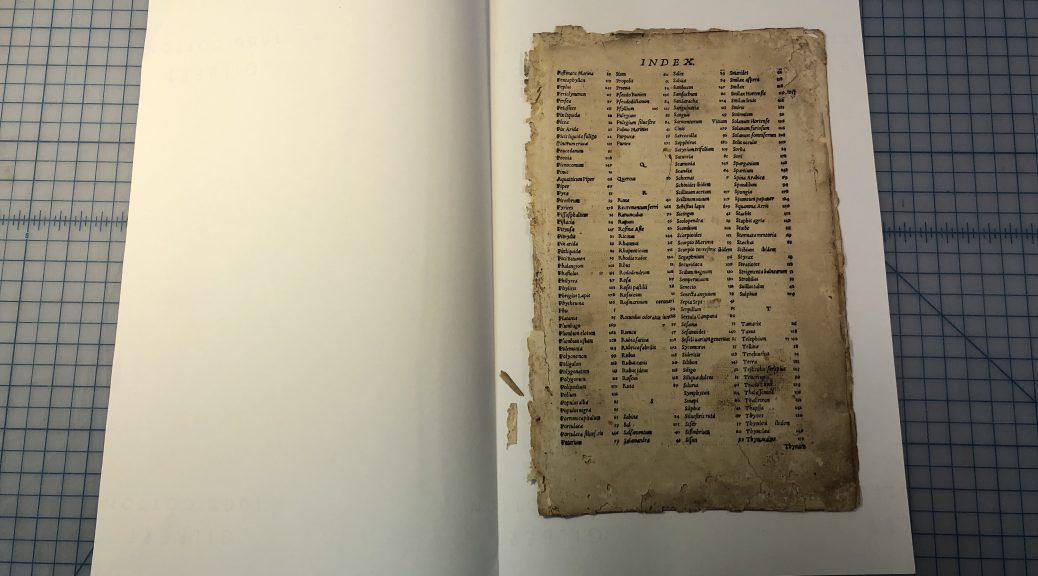

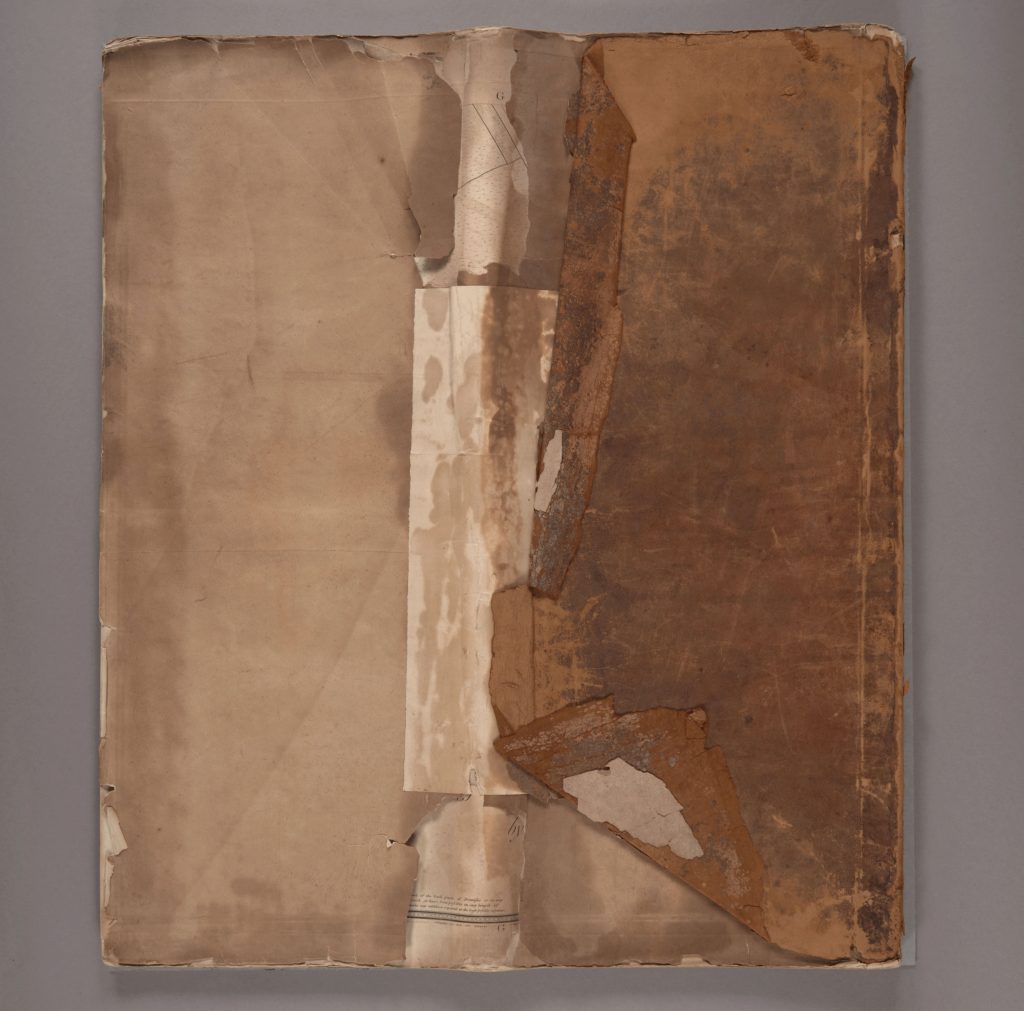

For the past several months, I’ve been working on (and writing about) a 16th century German book which has a number of problems. The textblock was already in pieces, but then it had to be taken apart completely for treatment. I was worried about keeping all the little bits organized, so that nothing would be lost or put in the wrong order as it underwent this long and multi-stage process.

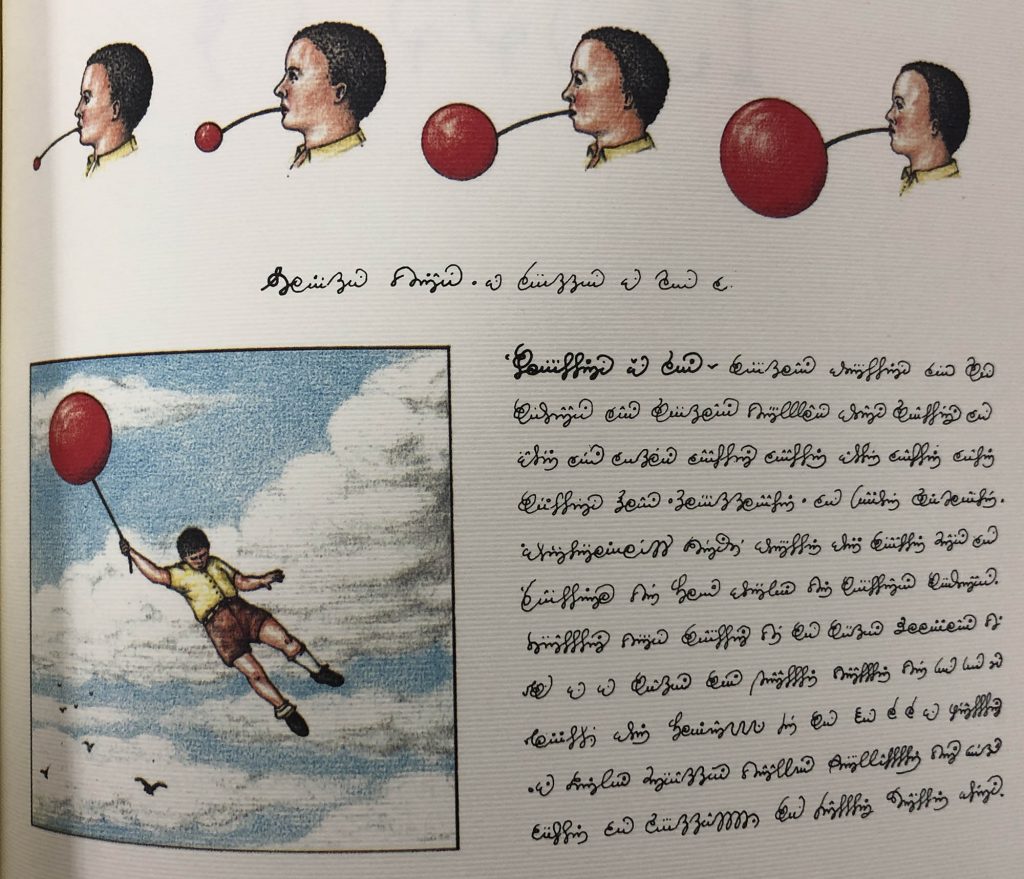

As part of the pre-treatment documentation process, I collated the book using a digital copy of the same edition hosted by the Bavarian State Library. Early books are not paginated in the same way as modern ones, so you have to look for other clues to maintain the correct order. To help, I numbered each leaf in pencil before disbinding. The textblock is organized into sections of three folios. Some of the folds are intact with a little damage, but many of them have split entirely, leaving individual leaves. Each separated section was placed into a numbered paper folder, including any separated little bits of paper from that section.

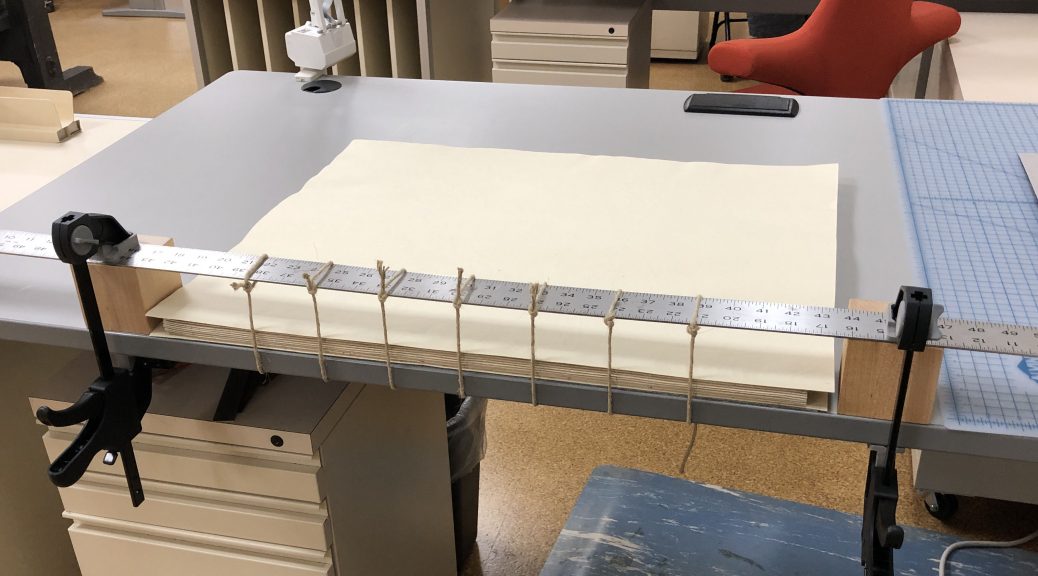

Throughout the treatment, I have been trying to work on one section at a time to keep all the parts in easily manageable groups. This was true for washing, resizing, and mending.

Throughout the treatment, I have been trying to work on one section at a time to keep all the parts in easily manageable groups. This was true for washing, resizing, and mending.

Since all of the sections are composed of three folios, I started making marks on the outside of the paper folder to keep track of what I had finished in each packet. For example, in the mending and guarding stage it is best to work from the inside of the section to the outside. It can be a rather drawn out process of adding mends, then leaving them to dry under weight. I would cross out the number 3 as I finished the most interior folio, proceeding through the entire textblock before starting on the middle folios. Over the course of a couple of weeks doing this, it was very easy to just look through the stack of folders and see where to continue.

Since all of the sections are composed of three folios, I started making marks on the outside of the paper folder to keep track of what I had finished in each packet. For example, in the mending and guarding stage it is best to work from the inside of the section to the outside. It can be a rather drawn out process of adding mends, then leaving them to dry under weight. I would cross out the number 3 as I finished the most interior folio, proceeding through the entire textblock before starting on the middle folios. Over the course of a couple of weeks doing this, it was very easy to just look through the stack of folders and see where to continue.

The first two sections have the most losses, so I’m still finishing some of the stabilization/infills on those – but overall the textblock is looking much improved!

(still in process, but you can compare to the “before” photo to see the progress)

There are probably many strategies for keeping the different parts of your treatments organized, but I have found this low-tech one to be very straightforward and helpful for books at least. What strategies/tools do you use?

Now that it’s in the machine and heated up, I will be spending the next hour looking around the lab for anything that I can stamp. The back of my Moleskine notebook was the first thing to go.

Now that it’s in the machine and heated up, I will be spending the next hour looking around the lab for anything that I can stamp. The back of my Moleskine notebook was the first thing to go.