A lot of different materials go into producing a book’s binding and for centuries bookbinders have used pieces of broken or discarded books to produce new ones. We often find scraps of manuscript or print, on either paper or parchment, used as spine linings, as endsheets, or even as full covers for bindings (see images from the collections of Princeton or Library of Congress here). We often describe this practice as waste (manuscript waste, printer’s waste, binding waste, etc.). Some important texts have only survived because they were reused in this way.

While some examples of binding waste (like covers or endleaves) are immediately obvious, others are only revealed by damage. This early 18th century printed book came in for rehousing recently and shows some of the fascinating things that can be hidden beneath the surface.

In areas where leather corners have come off or the sprinkled brown paper sides have lifted you can see some text peaking through. The book itself is printed in Latin, but the waste used in the binding is in German. This edition was printed in Munich, so it makes sense that a contemporary binding would also include waste in German.

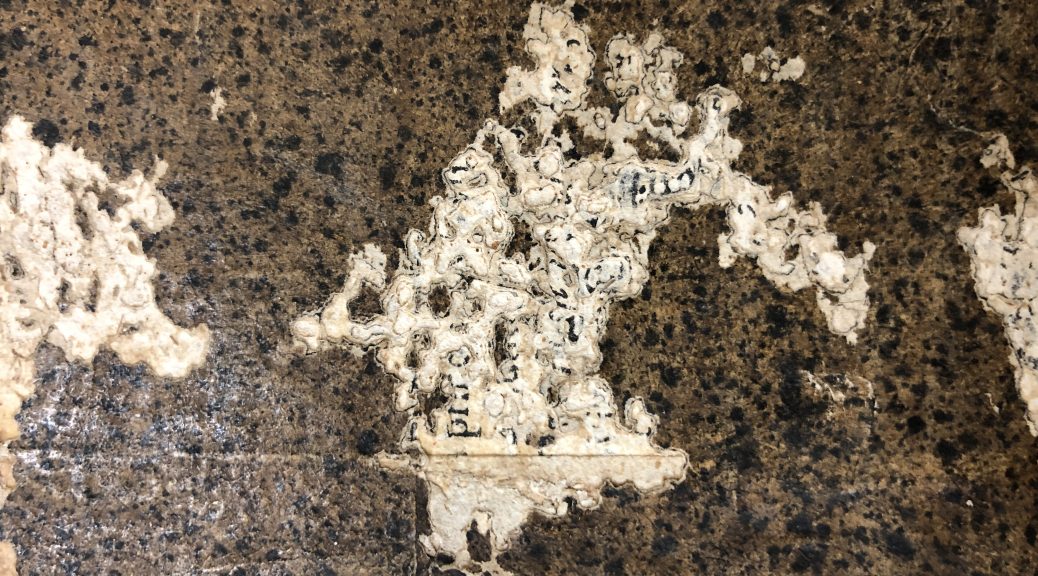

In addition to the mechanical damage to the paper covering material along the board corners and edges, there is also some insect damage along the faces of both boards.

The insects have eaten away at the first several layers of binding material, revealing many layers of print – sometimes in different orientations. It seems our print waste was not just used as a board lining, but the boards themselves are composed of many layers of print laminated together.

The insects have eaten away at the first several layers of binding material, revealing many layers of print – sometimes in different orientations. It seems our print waste was not just used as a board lining, but the boards themselves are composed of many layers of print laminated together.

I am usually not excited to encounter an insect-damaged book, but in this case the bugs have created a rather beautiful object – almost like a typographic topographical map – and have revealed useful information about its production.