Images from the Robert L. Eichelberger Collection

![]() Browse images in this category

Browse images in this category![]() Guide to the Robert L. Eichelberger Papers, 1728-1998 (bulk 1942-1949)

Guide to the Robert L. Eichelberger Papers, 1728-1998 (bulk 1942-1949)

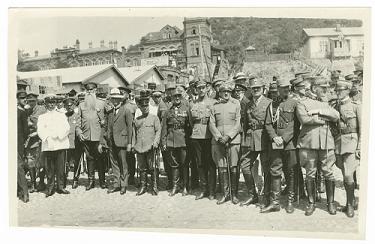

This digital collection of photographs and photo-postcards from the Robert L. Eichelberger Collection at Duke University’s David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library provide unique visual documentation of both American involvement in the Russian Civil War (1918-1921) and daily life during war-time in an ethnically and religiously diverse region on the border of three major 20th-century powers (Russia, Japan, and China).

This digital collection of photographs and photo-postcards from the Robert L. Eichelberger Collection at Duke University’s David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library provide unique visual documentation of both American involvement in the Russian Civil War (1918-1921) and daily life during war-time in an ethnically and religiously diverse region on the border of three major 20th-century powers (Russia, Japan, and China).

General Robert L. Eichelberger (1886-1961), a 1909 West Point graduate, served with distinction in the U.S. Army, and is perhaps most famous for his role in the occupation of Japan after World War II. Although the bulk of the 30,000 item collection of personal papers does indeed date from that era, a series of unique and heretofore little-known photographic images of the Russian Civil War in eastern Siberia recall one of the general’s earliest assignments.

Eichelberger was posted to Siberia in 1918 to serve as assistant chief of staff, Operations Division, and chief intelligence officer with the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF), which was dispatched to Russia by President Woodrow Wilson on a mission that constituted America’s first attempt to use its armed forces for peacekeeping purposes. Over the course of Eichelberger’s two-year tour of duty, he oversaw an intelligence network that extended over 5,000 miles into the Ural Mountains. In his official capacity as America’s chief intelligence officer in Siberia, he interviewed (frequently over a bottle of vodka) hundreds of Russians from all walks of life, including “everything from a Baron to a prostitute.” The intelligence gathered through his efforts and the reports generated through his examination of the data, allowed his commanding officer, Lieutenant-General William S. Graves, to determine a consistent American policy amidst “competing signals” from both Washington and the Inter-Allied Military Council, the ten-nation committee composed of American, British, French, and Japanese officers that debated, formulated, and tried to implement a coherent Allied policy for Siberia and eastern Russia between 1918 and 1920.

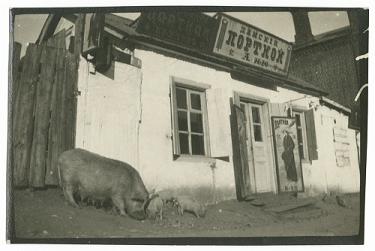

Materials in the Eichelberger Papers that pertain to his participation in the AEF’s incursion into Siberia are grouped into two series. The Military Papers Series includes typed letters, handwritten notes, intelligence summaries, memoranda and reports, and leaflets as well as maps. The Picture Series, which is comprised of both photographs and photo-postcards, not only complements the written record of Eichelberger’s tour of duty in eastern Siberia, but serves as an important primary source in its own right. This collection includes two albums of panoramic landscapes and official AEF photos, as well as a much larger assortment of images shot with a small portable camera by Eichelberger and his fellow officers. Unlike the album photos, these are much less romanticized images of everyday life in eastern Siberia. Despite their seemingly more ethnographic nature, however, this second set of photos and photo-postcards is no less ideological than any of the other images in the Eichelberger collection. Although the temptation to treat them as a somehow more authentic representation of the past is very great, it would be a mistake to do so. Instead, these photos can be seen as Eichelberger’s commentary on the situation in which the American Expeditionary Force in general, and Eichelberger in particular, found himself.

Materials in the Eichelberger Papers that pertain to his participation in the AEF’s incursion into Siberia are grouped into two series. The Military Papers Series includes typed letters, handwritten notes, intelligence summaries, memoranda and reports, and leaflets as well as maps. The Picture Series, which is comprised of both photographs and photo-postcards, not only complements the written record of Eichelberger’s tour of duty in eastern Siberia, but serves as an important primary source in its own right. This collection includes two albums of panoramic landscapes and official AEF photos, as well as a much larger assortment of images shot with a small portable camera by Eichelberger and his fellow officers. Unlike the album photos, these are much less romanticized images of everyday life in eastern Siberia. Despite their seemingly more ethnographic nature, however, this second set of photos and photo-postcards is no less ideological than any of the other images in the Eichelberger collection. Although the temptation to treat them as a somehow more authentic representation of the past is very great, it would be a mistake to do so. Instead, these photos can be seen as Eichelberger’s commentary on the situation in which the American Expeditionary Force in general, and Eichelberger in particular, found himself.

Almost from the start, the situations in which the troops of the American Expedition found itself was very complicated, if not completely untenable. As soon as they arrived in eastern Siberia, American troops realized that the most proximate reason for the White House-initiated incursion, namely, helping the Allies to re-establish an eastern front by providing military assistance to the so-called “Czech Legion” was a fraud. After only a few months on the ground, Eichelberger came to disagree with the assessment of the mission of American troops in Siberia (that is, the idea that guarding the Siberian railroads would provide economic relief to the Russian people, ensure domestic stability, and increase the changes for the triumph of democracy in Russia). He reported that the anti-Communist “White” forces used the railroad for their periodic “recruiting expeditions,” during which they killed, branded, or tortured any peasant who refused to join their ranks. Needless to say, these punitive expeditions drove the Russian peasants into the ranks of the Bolsheviks – a result that “American troops contributed to” by guarding the railroad that made this “oppression” possible. Eichelberger concluded that the US presence in Siberia provided support to “a rotten, monarchistic” government that “has the sympathy of only a very few of the people.” As early as Oct. 1919, he recommended withdrawal of US troops from Russia because it was a “hot bed of murder and oriental intrigue” and “a dirty place for Americans to be.”

Almost from the start, the situations in which the troops of the American Expedition found itself was very complicated, if not completely untenable. As soon as they arrived in eastern Siberia, American troops realized that the most proximate reason for the White House-initiated incursion, namely, helping the Allies to re-establish an eastern front by providing military assistance to the so-called “Czech Legion” was a fraud. After only a few months on the ground, Eichelberger came to disagree with the assessment of the mission of American troops in Siberia (that is, the idea that guarding the Siberian railroads would provide economic relief to the Russian people, ensure domestic stability, and increase the changes for the triumph of democracy in Russia). He reported that the anti-Communist “White” forces used the railroad for their periodic “recruiting expeditions,” during which they killed, branded, or tortured any peasant who refused to join their ranks. Needless to say, these punitive expeditions drove the Russian peasants into the ranks of the Bolsheviks – a result that “American troops contributed to” by guarding the railroad that made this “oppression” possible. Eichelberger concluded that the US presence in Siberia provided support to “a rotten, monarchistic” government that “has the sympathy of only a very few of the people.” As early as Oct. 1919, he recommended withdrawal of US troops from Russia because it was a “hot bed of murder and oriental intrigue” and “a dirty place for Americans to be.”

To a certain extent, this orientalizing discourse about the supposedly-inherent corruption and inferiority of Russian society also found its way into the visual language of some of Eichelberger’s photos, particularly those depicting the diverse peoples of eastern Siberia or their exotic modes of transportation (junks, camels, droshki). In effect, if not in intention, Eichelberger’s photos did much more than merely document the multi-ethnic and multi-confessional “reality” of life during the Russian Civil War in eastern Siberia. By directing his camera at only certain racial types or social situations, Eichelberger took the opportunity to re-assert the superiority of his own nation, gender, and race, if only in the photos that he took, annotated, and included in the letters that he sent home to his adoring wife. Eichelberger’s ability to photograph and thereby to objectify the Oriental “other” allowed him (and other members of the American Expeditionary Force) to do nothing less than snatch a symbolic victory out of the jaws of defeat.

To a certain extent, this orientalizing discourse about the supposedly-inherent corruption and inferiority of Russian society also found its way into the visual language of some of Eichelberger’s photos, particularly those depicting the diverse peoples of eastern Siberia or their exotic modes of transportation (junks, camels, droshki). In effect, if not in intention, Eichelberger’s photos did much more than merely document the multi-ethnic and multi-confessional “reality” of life during the Russian Civil War in eastern Siberia. By directing his camera at only certain racial types or social situations, Eichelberger took the opportunity to re-assert the superiority of his own nation, gender, and race, if only in the photos that he took, annotated, and included in the letters that he sent home to his adoring wife. Eichelberger’s ability to photograph and thereby to objectify the Oriental “other” allowed him (and other members of the American Expeditionary Force) to do nothing less than snatch a symbolic victory out of the jaws of defeat.

All the quotes from Eichelberger’s correspondence are taken from the 1991 Duke University doctoral dissertation of Paul Chwialkowski, entitled “A ‘Near Great’ General: The Life and Career of Robert L. Eichelberger” (Ph. D., Duke University, 1991), published under the title In Caesar’s Shadow: The Life of General Robert Eichelberger [= Contributions in military studies, no. 141] (Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 1993).