Earlier this month, I was invited to give some remarks on “The Commons Approach” at the LYRASIS Leaders Forum, which was held at the Duke Gardens. We have a great privilege and opportunity as part of the Duke University Libraries to participate in many different communities and projects, and it is one of the many reasons I love working at Duke. The following is the talk I gave, which shares some personal and professional reflections of the Commons.

The Commons Approach is something that I have been committed to for almost the entirety of my library career, which is approaching twenty years. When I start working in libraries at Lehigh University, I came into the community with little comprehensive about the inner workings of libraries. I had no formal library training, and my technology education, training, and work experience had been developed through experimentation and learning by doing. Little did I know at the time, I was benefiting from small models of the Commons, or even how to define it.

There are a number of definitions of Commons, but one definition I like best that I found in Wikipedia is “a general term for shared resources in which each stakeholder has an equal interest”. There are many contexts:

- natural resources – air, water, soil

- cultural norms and shared values

- public lands that no one owns

- information resources that are created collectively and shared among communities, free for re-use

The librarians and library staff around me at Lehigh brought me into their Commons, and gave me the time and space to learn about the norms, shared values, terminology, language, jargon, and collective priorities of libraries so that I could begin to apply them with my skills and experiences and be an active contributor to the Commons of Libraries. As I began to become more unified with them in the commons approach, my diverse work experience and skill added to our community. I recognized that I belonged, that I was now a stakeholder with an equal interest, and that I could create and share among the broader library community.

If we start with the foundation that libraries are naturally driven towards a Commons approach within their own campus or organization, we can examine the variety of models of projects and communities that extend the Commons Approach.

- Open Source Software Projects (Apache Model)

- earned trust through contributions over time

- primarily a complete volunteering of time and effort

- peer accountability, limited risk of power struggles

- tends to choose the most open license possible

- Community Source Projects (Kuali OLE, Fedora)

- “those who bring the gold set the rules”

- The more commitment you make in resources, the more privilege and opportunity you receive

- Dependent on defined governance around both rank of commitment and representation

- Tends to choose open licensing that offers most protection and control

- Membership initiatives (OLE [before and after Kuali], APTrust, DPN, SPN)

- Typically tiered, proportional model focused primarily on financial contributions

- Convergence around a strategic initiative, project, or outcome

- Pooled financial resources to develop and sustain a solution

- Consortial Partnerships (Informal, Formal, Mixed)

- Location- or context-based partnership to collaborate

- Defined governance structure

- Informal or formal

- National Initiatives (Code4Lib, DPLA, DLF)

- Annual conferences or meetings

- Distributed communications commons (listserv, Slack, website)

- Coordinated around large ideas or contexts and sharing local ideas / projects to build grass roots change

- Focused on democratizing opportunity for sharing and collaboration

- Community Projects with Corporate Sponsors (for-profit, not-for-profit)

- Hybrid or mixed models of community source or membership initiatives

- Corporate services support to implementers

- Challenges in governance of priorities between sponsor and community

NOTE: There are more models and nuances to these models.

Benefits and Challenges

Each of these models has benefits and challenges. One of the issues that I have become particularly interested in, and consistently advocate for, is creating an environment that promotes diversity of participants. The Community Source model of privileging those who bring the gold, for example, tends to bias larger organizations that have financial and human resource flexibility and requires clear proportional investment tiers that recognize varied sizes of organizations wanting to join the community. But while contribution levels can be defined at varied tiers, costs are constant and usually fixed, especially staffing costs, which will put pressure on the community to sustain. A smaller, startup community thus needs larger investments to incubate the project no matter how equal they intend to share the ownership across all of the stakeholders. Thus:

- How do we develop our communities to fully embrace a Commons Approach that gives each stakeholder equal opportunity that also embraces differences of the organizations within the community?

- How do we setup our communities that empower smaller organizations not only to join but to lead?

- How we do setup our communities to encourage well-resourced organizations to contribute without automatically assuming leadership or control?

Open Source

My first opportunity to experience the Commons Approach outside of my own library was as a member of the VuFind project. While Villanova University led and sponsored the project, Andrew Nagy, the founding developer, contributed his hard work to the whole community and invited others to co-develop. As you gained the trust of the lead developers in what you contributed, you earned more responsibility and opportunity to work on the core code. If you chose to focus on specific contributions, you became the lead developers of that part of the code. It was all voluntary and all contributing to a common purpose: to develop an open source faceted discovery platform. As leaders transitioned to new jobs or new organizations, some stayed on the project, and some were replaced with other community members who had earned their opportunity.

Community Source

While I was working at Lehigh and participating in the Open Library Environment as a membership model, it was simpler for me to feel like I belonged because each member had a single member on the governance group. I was an equal member, and Lehigh had an equal stake. We held in Common priorities for our community, for the project, and for the outcome. We held in Common that each of us represented libraries from different contexts: private, public, large, small, US-based, and International. We held in Common the priority to grow and attract other libraries of various sizes, contexts, and geographic locations. It felt idealistic.

The ideal shattered when OLE joined the Kuali Foundation and the model changed from membership to Community Source. The rules of that model were different, and thus the foundation of their Commons was also different. While tiers of financial contribution were still in place, it was clear that the more resources your organization brought, the more influence your organization would have. Vendors were also members of the community, and they put in a different level and category of resources.

Moreover, there were joint governance committees overseeing projects that multiple projects were using at the same time. Which project’s priorities would be addressed first depended on which project was paying more into that project. I quickly realized that OLE, which was not paying as much as others, would not be getting its needs addressed. To be fair, this structure worked for some of the Kuali projects and worked well. But it not a Commons approach that the Open Library Environment had been committed to, and it was not the best model for that community to be successful.

Consortial Partnerships

Consortial partnerships are critical for local, regional, and national collaboration, and these partnerships are centered on a variety of common strategies, from buying or licensing collections to resource sharing to digital projects. There are formal and informal consortia, some that are decades old and some that are very new. As libraries continue to face constrained resources, banding together through these common constraints will be more and more critical to providing our users the level of service we expect to provide – another common thread: excellence.

National Initiatives

National initiatives have been getting a lot of press this year, mostly for difficult reasons. There are also a variety of contexts for national initiatives, but most of the ones we likely consider are joined by a shared commitment to a topic, theme, or challenge. Code4Lib began in 2003 as a listserv of library programmers hoping to find community with others in the library, museum, and archives community. Code4Lib started meeting annually when it became clear it would be beneficial to share projects and ideas in person, hack and design things together, and find new ways to collaborate out in the open.

The Digital Library Federation is a community of practitioners who advance research, learning, social justice, and the public good through the creative design and wise application of digital library technologies. The Digital Public Library of America was founded to maximize public access to the collections of historical and cultural organizations across the country.

The methods each of these national initiatives are quite different from each other, but they have focus on a Commons Approach that recognizes their collective effort is greater than the sum of their individual results.

Community Projects with Corporate Sponsors

The newest model of the Commons Approach is the hybrid open-source or community-source projects that include corporate sponsorship, hosting, or services. There are example of both for-profit and not-for-profit sponsorships, as well as a not-for-profit who tends to act at times like a for-profit, and the library community is continuing to have mixed reactions. Some libraries embrace this interest by corporate partners, while others outright reject the notion as a type of Trojan horse. Some are skeptical of specific corporations, while some have biases towards or against specific partners. This new paradigm challenges our notion of openness, but it also offers an opportunity to explore different means to the Commons Approach. The same elements apply – what are norms, values, terminology, language, jargon, and collective priorities that we share together? What benefits can each stakeholder bring to the community? Is there a diversity of participation, leadership, and contribution that creates inclusion? Are there new aspects to having corporate sponsors join that the library community cannot do on its own?

Economies of scale

One of these new aspects is developing new means of economies of scale, which is a good step to sustaining a Commons Approach. Economies of scale allows greater opportunity for libraries of different sizes and financial resources to work together. Open and community source projects in particular need solid financial planning, but great ideas and leadership are not limited to libraries with larger budgets or staff size. Continuing to increase the opportunity for diversity of the community will be a great outcome and encourage a broader adoption of the Commons Approach.

Yet project staffing and resources are usually fixed costs that are not kind to the attempts to enable libraries to make variable contributions. It requires a balance of large and small contributions from the community, and the entry of corporate sponsors has enable some new financial and infrastructure security missing in many projects and initiatives. Yet, as a community focused on common values, norms, and priorities, it is not disingenuous to use due diligence to ensure all members of the community, library and sponsor alike, are committed to the Commons Approach and not in it for a free ride or an ulterior motive.

New Paradigm as a Disruptive Force

And it is accurate to call this new paradigm a disruptive force to open- and community-source projects. It is up to the community to decide for itself what the best is for their future: embrace the disruption and adapt for the positive gains; hold true to their origins and continue on their path; or be torn apart by change, ignoring or forgetting their Common Approach foundation in the wake of the disruptive force.

Each of the models above have had some manner of corporate sponsorship examples, so we know there is success to be found regardless of the model. And there are still many examples that remain strong in their original framework. What I find encouraging, even in the difficult situations of the past year for many organizations, is that we are challenging our notions of how to develop these communities so that we can develop greater sustainability, greater participation from a more diverse and representative community, and achieve broader success of the Commons together – for our users, the most important connecting element of all.

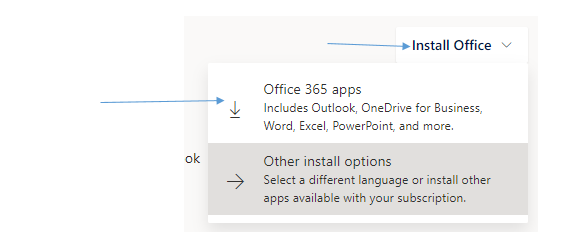

For the past year, developers in the Library’s Software Services department have been working to rebuild Duke’s

For the past year, developers in the Library’s Software Services department have been working to rebuild Duke’s