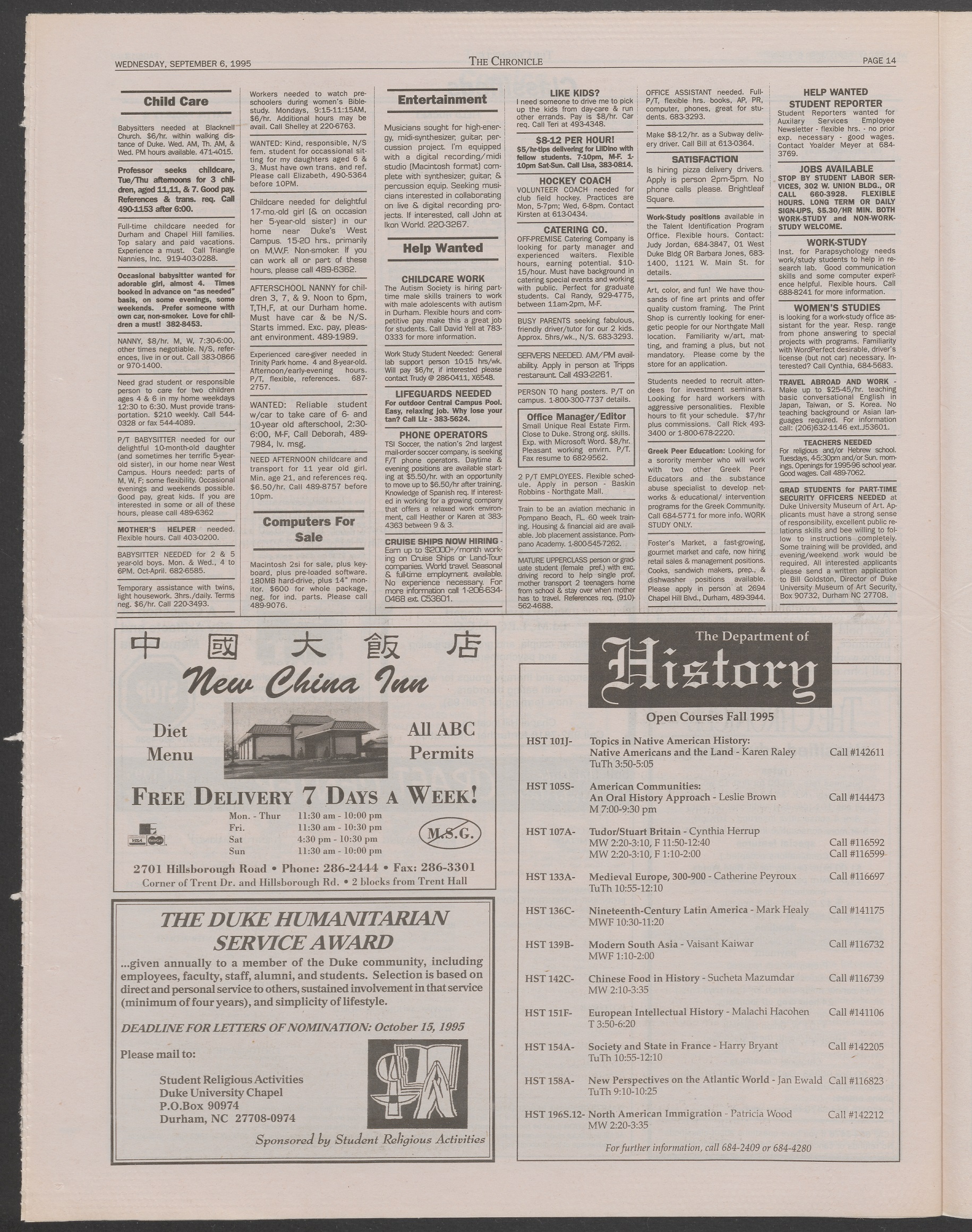

It takes a lot to build and publish digital collections as you can see from the variety and scope of the blog posts here on Bitstreams. We all have our internal workflows and tools we use to make our jobs easier and more efficient. The number and scale of activities going on behind the scenes is mind-boggling and we would never be able to do as much as we do if we didn’t continually refine our workflows and create tools and systems that help manage our data and work. Some of these tools are big, like the Duke Digital Repository (DDR), with its public, staff and backend interface used to preserve, secure, and provide access to digital resources,  while others are small, like scripts built to transform ArchiveSpace output into a starter digitization guides. In the Digital Production Center (DPC) we use a homegrown tool that not only tracks production statistics but is also used to do project projections and to help isolate problems that occur during the digitization process. This tool is a relational database that is affectionately named the Daily Work Report and has collected over 9 years of data on nearly every project in that time.

while others are small, like scripts built to transform ArchiveSpace output into a starter digitization guides. In the Digital Production Center (DPC) we use a homegrown tool that not only tracks production statistics but is also used to do project projections and to help isolate problems that occur during the digitization process. This tool is a relational database that is affectionately named the Daily Work Report and has collected over 9 years of data on nearly every project in that time.

A long time ago, in a newly minted DPC, supervisors and other Library staff often asked me, “How long will that take?”, “How many students will we need to digitize this collection?”, “What will the data foot print of this project be?”, “How fast does this scanner go?”, “How many scans did we do last year?”, “How many items is that?”. While I used to provide general information and anecdotal evidence to answer all of these questions, along with some manual hunting down of this information, it became more and more difficult to answer these questions as the number of projects multiplied, our services grew, the number of capture devices multiplied and the types of projects grew to include preservation projects, donor requests, patron request and exhibits.  Answering these seemingly simple questions became more complicated and time consuming as the department grew. I thought to myself, I need a simple way to track the work being done on these projects that would help me answer these recurring common questions.

Answering these seemingly simple questions became more complicated and time consuming as the department grew. I thought to myself, I need a simple way to track the work being done on these projects that would help me answer these recurring common questions.

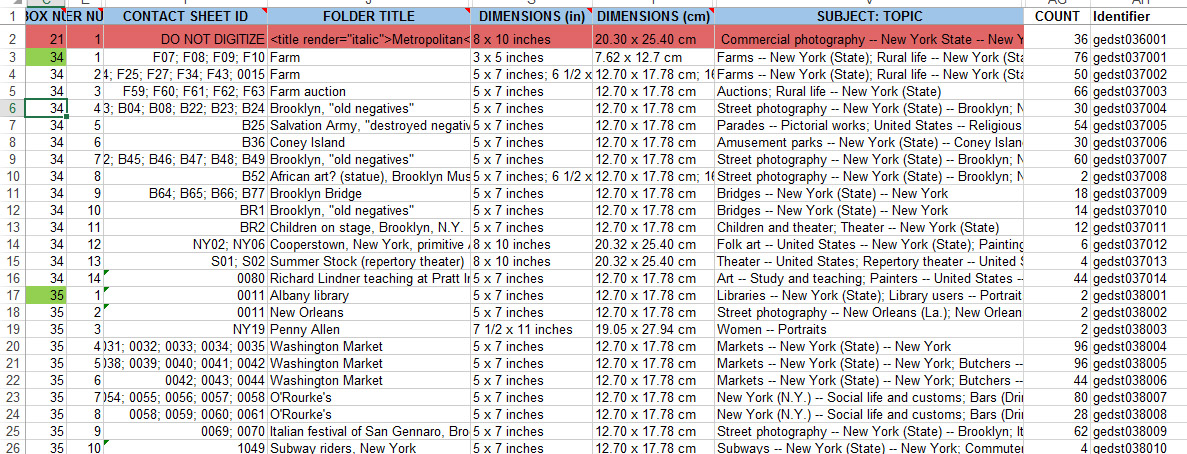

We were already using a FileMaker Pro database with a GUI interface as a checkout system to assign students batches of material to scan, but it was only tracking what student worked on what material. I decided I could build out this concept to include all of the data points needed to answer the questions above. I decided to use Microsoft Access because it was a common tool installed on every workstation in the department, I had used it before, and classes and instructional videos abound if I wanted to do anything fancy.

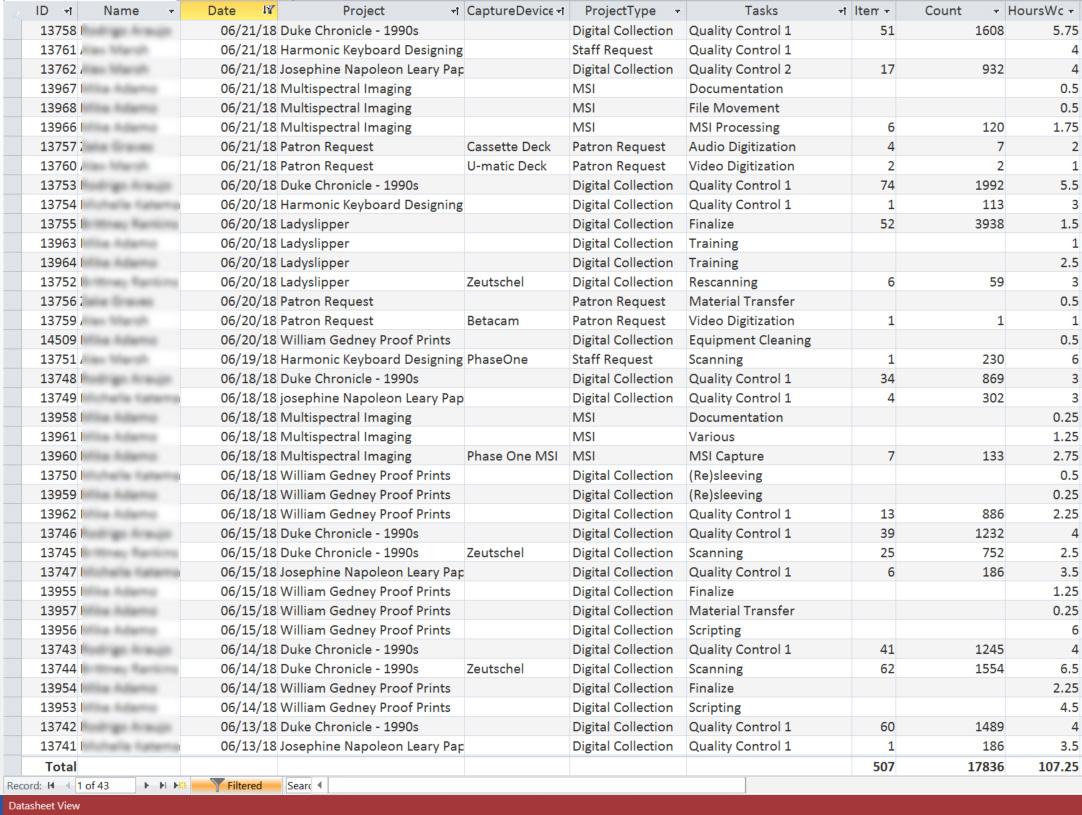

Enter the Daily Work Report (DWR). I created a number of discrete tables to hold various types of data: project names, digitization tasks, employee names and so on. These fields are connected to a datasheet represented as a form, which allowed for dropdown lists and auto filling for rapid and consistent entry of information.

At the end of each shift students and professionals alike fill out the DWR for each task they performed on each project and how long they worked on each task. These range from the obvious tasks of scanning and quality control to more minute tasks of derivative creation, equipment cleaning, calibration, documentation, material transfer, file movement, file renaming, ingest prep, and ingest.

Some of these tasks may seem minor and possibly too insignificant to record but they add up. They add up to ~30% of the time it takes to complete a project. When projecting the time it will take to complete a project we collect Scanning and Quality Control data from a similar project, calculate the time and add 30%.

Common Digitization Tasks

Task |

Hours | Overall % of project |

| Scanning | 406.5 | 57.9 |

| Quality Control 1 | 133 | 19 |

| Running Scripts | 24.5 | 3.5 |

| Collection Analysis | 21 | 3 |

| Derivative Creation | 20.5 | 2.9 |

| File Renaming | 15.5 | 2.2 |

| Material Transfer | 14 | 2 |

| Testing | 12.5 | 1.8 |

| Documentation | 10 | 1.4 |

| File Movement | 9.75 | 1.4 |

| Digitization Guide | 7 | 1 |

| Quality Control 2 | 6.75 | 1 |

| Training | 6 | 0.9 |

| Quality Control 3 | 5.5 | 0.9 |

| Stitching | 3 | 0.4 |

| Rescanning | 1.5 | 0.2 |

| Finalize | 1.5 | 0.2 |

| Troubleshooting | 1.5 | 0.2 |

| Conservation Consultation | 1 | 0.1 |

| Total | 701 | 100 |

New Project Estimates

Using the Daily Work Report’s Datasheet View, the database can be filtered by project, then by the “Scanning” task to get the total number of scans and the hours worked to complete those scans. The same can be done for the Quality Control task. With this information the average number of scans per hour can be calculated for the project and applied to the new project estimate.

Gather information from an existing project that is most similar to the project you are creating the estimate for. For example, if you need to develop an estimate for a collection of bound volumes that will be captured on the Zeutschel you should find a similar collection in the DWR to run your numbers.

Gather information from an existing project that is most similar to the project you are creating the estimate for. For example, if you need to develop an estimate for a collection of bound volumes that will be captured on the Zeutschel you should find a similar collection in the DWR to run your numbers.

Gather data from an existing project:

Scanning

- Number of scans = 3,473

- Number of hours = 78.5

- 3,473/78.5 = 2/hr

Quality Control

- Number of scans = 3,473

- Number of hours = 52.75

- 3,473/52.75 = 8/hr

Apply the per hour rates to the new project:

Estimated number of scans: 7,800

- Scanning: 7,800 / 44.2/hr = 176.5 hrs

- QC: 7,800 / 68.8/hr = 113.4 hrs

- Total: 290 hrs

- + 30%: 87 hrs

- Grand Total: 377 hrs

Rolling Production Rate

When an update is required for an ongoing project the Daily Work Report can be used to see how much has been done and calculate how much longer it will take. The number of images scanned in a collection can be found by filtering by project then by the “Scanning” Task. That number can then be subtracted from the total number of scans in the project. Then, using a similar project to the one above you can calculate the production rate for the project and estimate the number of hours it will take to complete the project.

Scanning

- Number of scans in the project = 7,800

- Number of scans completed = 4,951

- Number of scans left to do = 7,800 – 4,951 = 2,849

Scanning time to completion

- Number of scans left = 2,849

- 2,849/42.4/hr = 2 hrs

Quality Control

- Number of files to QC in the project = 7,800

- Number of files completed = 3,712

- Number of files left to do = 7,800 – 3,712 = 4,088

QC hours to completion

- Number of scans left to scan = 4,088

- 4,088/68.8 = 4 hrs

The amount of time left to complete the project

- Scanning – 67.2 hrs

- Quality Control – 59.4 hrs

- Total = 126.2 hrs

- + 30% = 38

- Grand Total = 164.2 hrs

Isolate an error

Errors inevitably occur during most digitization projects. The DWR can be used to identify how widespread the error is by using a combination of filtering, the digitization guide (which is an inventory of images captured along with other metadata about the capture process), and inspecting the images. As an example, a set of files may be found to have no color profile. The digitization guide can be used to identify the day the erroneous images were created and who created them. The DWR can be used to filter by the scanner operator and date to see if the error is isolated to a particular person, a particular machine or a particular day. This information can then be used to filter by the same variables across collections to see if the error exists elsewhere. The result of this search can facilitate retraining, recalibrating of capture devices and also identify groups of images that need to be rescanned without having to comb through an entire collection.

While I’ve only touched on the uses of the Daily Work Report, we have used this database in many different ways over the years. It has continued to answer those recurring questions that come up year after year. How many scans did we do last year? How many students worked on that multiyear project? How many patron requests did we complete last quarter? This database has helped us do our estimates, isolate problems and provide accurate updates over the years. For such a simple tool it sure does come in handy.