How many times each day to you type something into a search box on the web and click “Search?” Have you ever wondered what happens behind the scenes to make this possible? In this post I’ll show how search works on the Duke University Libraries Catalog. I’ll trace the journey of how search works from metadata in a MARC record (where our bibliographic data is stored), to transforming that data into something we can index for searching, to how the words you type into the search box are transformed, and then finally how the indexed records and your search interact to produce a relevance ranked list of search results. Let’s get into the weeds!

A MARC record stores bibliographic data that we purchase from vendors or are created by metadata specialists who work at Duke Libraries. These records look something like this:

In an attempt to keep this simple, let’s just focus on the main title of the record. This is information recorded in the MARC record’s 245 field in subfields a, b, f, g, h, k, n, p, and s. I’m not going to explain what each of the subfields is for but the Library of Congress maintains extensive documentation about MARC field specifications (see 245 – Title Statement (NR)). Here is an example of a MARC 245 field with a linked 880 field that contains the equivalent title in an alternate script (just to keep things interesting).

=245 10$6880-02$aUrbilder ;$bBlossoming ; Kalligraphie ; O Mensch, bewein' dein' Sünde gross (Arrangement) : for string quartet /$cToshio Hosokawa.

=880 10$6245-02/{dollar}1$a原像 ;$b開花 ; 書 (カリグラフィー) ほか : 弦楽四重奏のための /$c細川俊夫.

The first thing that has to happen is we need to get the data out of the MARC record into a more computer friendly data format — an array of hashes, which is just a fancy way of saying a list of key value pairs. The software reads the metadata from the MARC 245 field, joins all the subfields together, and cleans up some punctuation. The software also checks to see if the title field contains Arabic, Chinese, Japanese, Korean, or Cyrillic characters, which have to be handled separately from Roman character languages. From the MARC 245 field and its linked 880 field we end up with the following data structure.

"title_main": [

{

"value": "Urbilder ; Blossoming ; Kalligraphie ; O Mensch, bewein' dein' Sünde gross (Arrangement) : for string quartet"

},

{

"value": "原像 ; 開花 ; 書 (カリグラフィー) ほか : 弦楽四重奏のための",

"lang": "cjk"

}

]

We send this data off to an ingest service that prepares the metadata for indexing.

The data is first expanded to multiple fields.

{"title_main_indexed": "Urbilder ; Blossoming ; Kalligraphie ; O Mensch, bewein' dein' Sünde gross (Arrangement) : for string quartet",

"title_main_vernacular_value": "原像 ; 開花 ; 書 (カリグラフィー) ほか : 弦楽四重奏のための",

"title_main_vernacular_lang": "cjk",

"title_main_value": "原像 ; 開花 ; 書 (カリグラフィー) ほか : 弦楽四重奏のための / Urbilder ; Blossoming ; Kalligraphie ; O Mensch, bewein' dein' Sünde gross (Arrangement) : for string quartet"}

title_main_indexed will be indexed for searching.

title_main_vernacular_value holds the non Roman version of the title to be indexed for searching.

title_main_vernacular_lang holds information about the character set stored in title_main_vernacular_value.

title_main_value holds the data that will be stored for display purposes in the catalog user interface.

We take this flattened, expanded set of fields and apply a set of rules to prepare the data for the indexer (Solr). These rules append suffixes to each field and combine the two vernacular fields to produce the following field value pairs. The suffixes provide instructions to the indexer about what should be done with each field.

{"title_main_indexed_tsearchtp": "Urbilder ; Blossoming ; Kalligraphie ; O Mensch, bewein' dein' Sünde gross (Arrangement) : for string quartet",

"title_main_cjk_v": "原像 ; 開花 ; 書 (カリグラフィー) ほか : 弦楽四重奏のための",

"title_main_t_stored_single": "原像 ; 開花 ; 書 (カリグラフィー) ほか : 弦楽四重奏のための / Urbilder ; Blossoming ; Kalligraphie ; O Mensch, bewein' dein' Sünde gross (Arrangement) : for string quartet" }

When sent to the indexer the fields are further transformed.

| Suffixed Source Field | Solr Field | Solr Field Type | Solr Stored/Indexed Values |

|---|---|---|---|

| title_main_indexed_tsearchtp | title_main_indexed_t | text stemmed | urbild blossom kalligraphi o mensch bewein dein sund gross arrang for string quartet |

| title_main_indexed_tsearchtp | title_main_indexed_tp | text unstemmed | urbilder blossoming kalligraphie o mensch bewein dein sunde gross arrangement for string quartet |

| title_main_cjk_v | title_main_cjk_v | chinese, japanese, korean text | 原 像 开花 书 か り く ら ふ ぃ い ほか 弦乐 亖 重奏 の ため の |

| title_main_t_stored_single | title_main | stored string | 原像 ; 開花 ; 書 (カリグラフィー) ほか : 弦楽四重奏のための / Urbilder ; Blossoming ; Kalligraphie ; O Mensch, bewein’ dein’ Sünde gross (Arrangement) : for string quartet |

These are all index time transformations. They occur when we send records into the index.

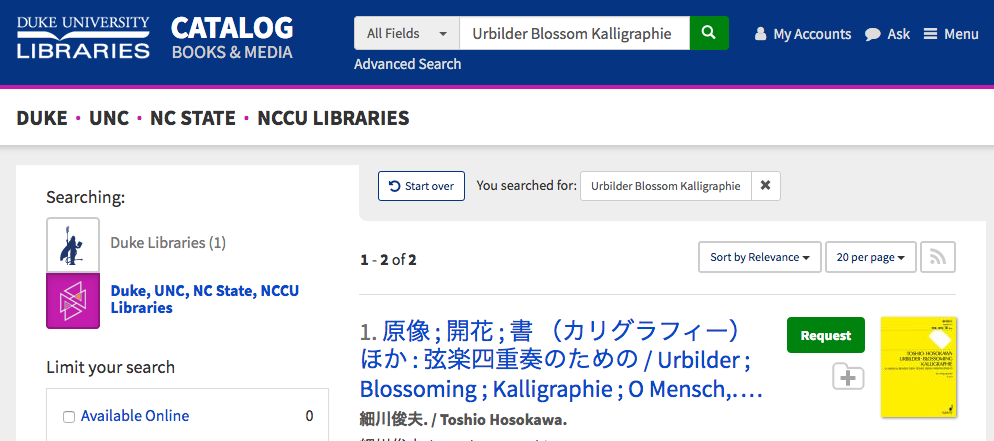

The query you enter into the search box also gets transformed in different ways and then compared to the indexed fields above. These are query time transformations. As an example, if I search for the terms “Urbilder Blossom Kalligraphie,” the following transformations and comparisons take place:

The values stored in the records for title_main_indexed_t are evaluated against my search string transformed to urbild blossom kalligraphi.

The values stored in the records for title_main_indexed_tp are evaluated against my search string transformed to urbilder blossom kalligraphie.

The values stored in the records for title_main_cjk_v are evaluated against my search string transformed to urbilder blossom kalligraphie.

Then Solr does some calculations based on relevance rules we configure to determine which documents are matches and how closely they match (signified by the relevance score calculated by Solr). The field value comparisons end up looking like this under the hood in Solr:

+(DisjunctionMaxQuery((

(title_main_cjk_v:urbilder)^50.0 |

(title_main_indexed_tp:urbilder)^500.0 |

(title_main_indexed_t:urbild)^100.0)~1.0)

DisjunctionMaxQuery((

(title_main_cjk_v:blossom)^50.0 |

(title_main_indexed_tp:blossom)^500.0 |

(title_main_indexed_t:blossom)^100.0)~1.0)

DisjunctionMaxQuery((

(title_main_cjk_v:kalligraphie)^50.0 |

(title_main_indexed_tp:kalligraphie)^500.0 |

(title_main_indexed_t:kalligraphi)^100.0)~1.0))~3

DisjunctionMaxQuery((

(title_main_cjk_v:"urbilder blossom kalligraphie")^150.0 |

(title_main_indexed_t:"urbild blossom kalligraphi")^600.0 |

(title_main_indexed_tp:"urbilder blossom kalligraphie")^5000.0)~1.0)

(DisjunctionMaxQuery((

(title_main_cjk_v:"urbilder blossom")^75.0 |

(title_main_indexed_t:"urbild blossom")^200.0 |

(title_main_indexed_tp:"urbilder blossom")^1000.0)~1.0)

DisjunctionMaxQuery((

(title_main_cjk_v:"blossom kalligraphie")^75.0 |

(title_main_indexed_t:"blossom kalligraphi")^200.0 |

(title_main_indexed_tp:"blossom kalligraphie")^1000.0)~1.0))

DisjunctionMaxQuery((

(title_main_cjk_v:"urbilder blossom kalligraphie")^100.0 |

(title_main_indexed_t:"urbild blossom kalligraphi")^350.0 |

(title_main_indexed_tp:"urbilder blossom kalligraphie")^3000.0)~1.0)

The ^nnnn indicates the relevance weight given to any matches it finds, while the ~n.n indicates the number of matches that are required from each clause to consider the document a match. Matches in fields with higher boosts count more than fields with lower boosts. You might notice another thing, that full phrase matches are boosted the most, two consecutive term matches are boosted slightly less, and then individual term matches are given the least boost. Furthermore unstemmed field matches (those that have been modified the least by the indexer, such as in the field title_main_indexed_tp) get more boost than stemmed field matches. This provides the best of both worlds — you still get a match if you search for “blossom” instead of “blossoming,” but if you had searched for “blossoming” the exact term match would boost the score of the document in results. Solr also considers how common the term is among all documents in the index so that very common words like “the” don’t boost the relevance score as much as less common words like “kalligraphie.”

I hope this provides some insight into what happens when you clicks search. Happy searching.

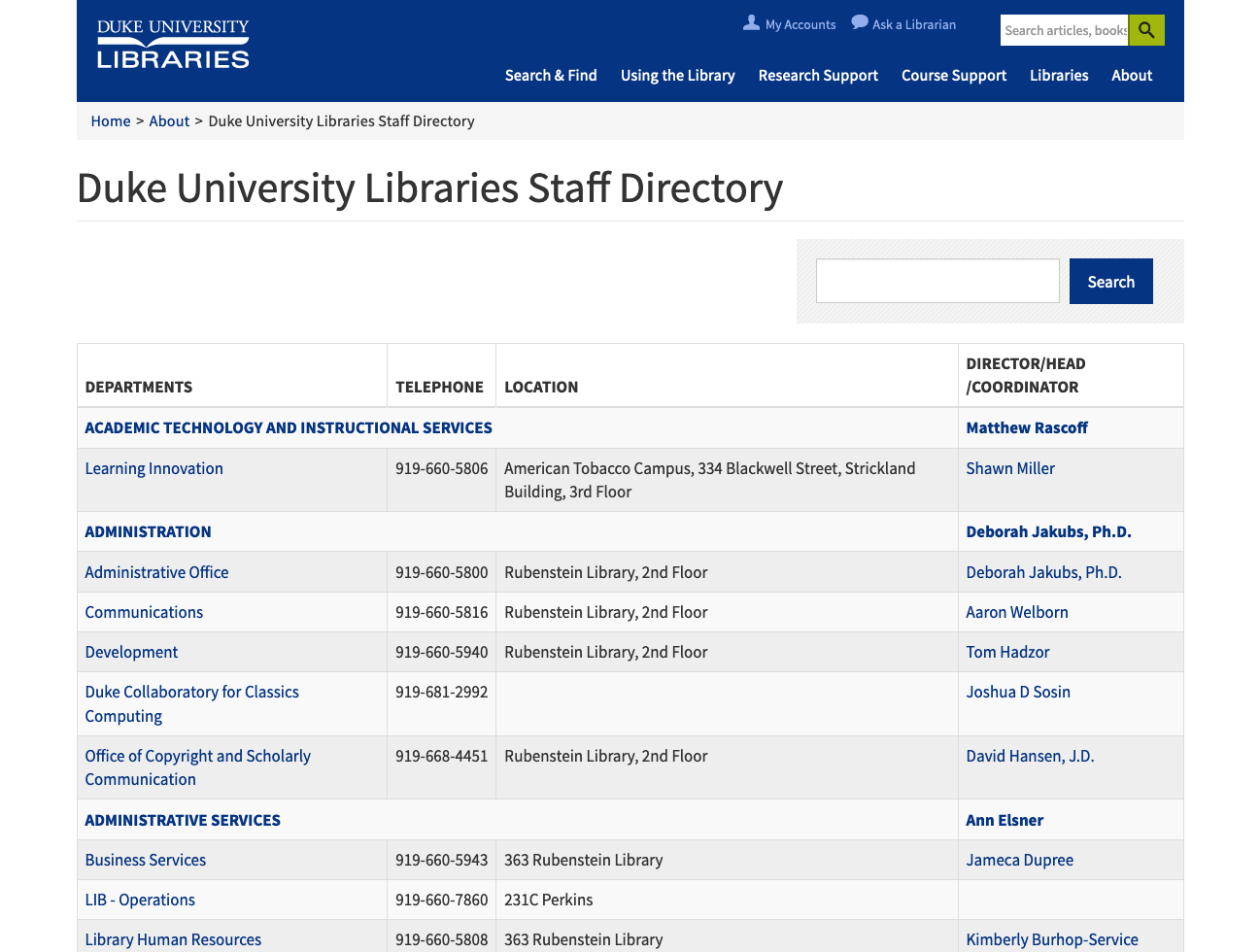

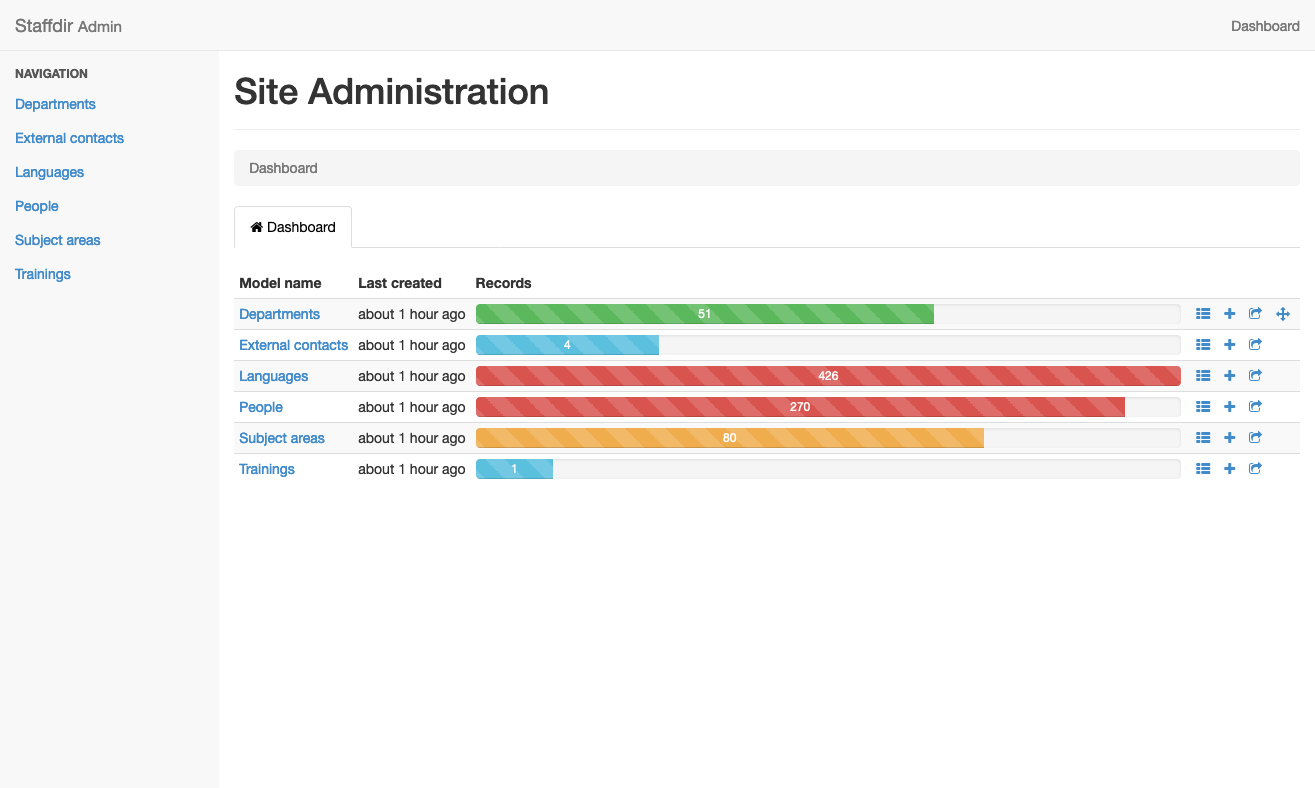

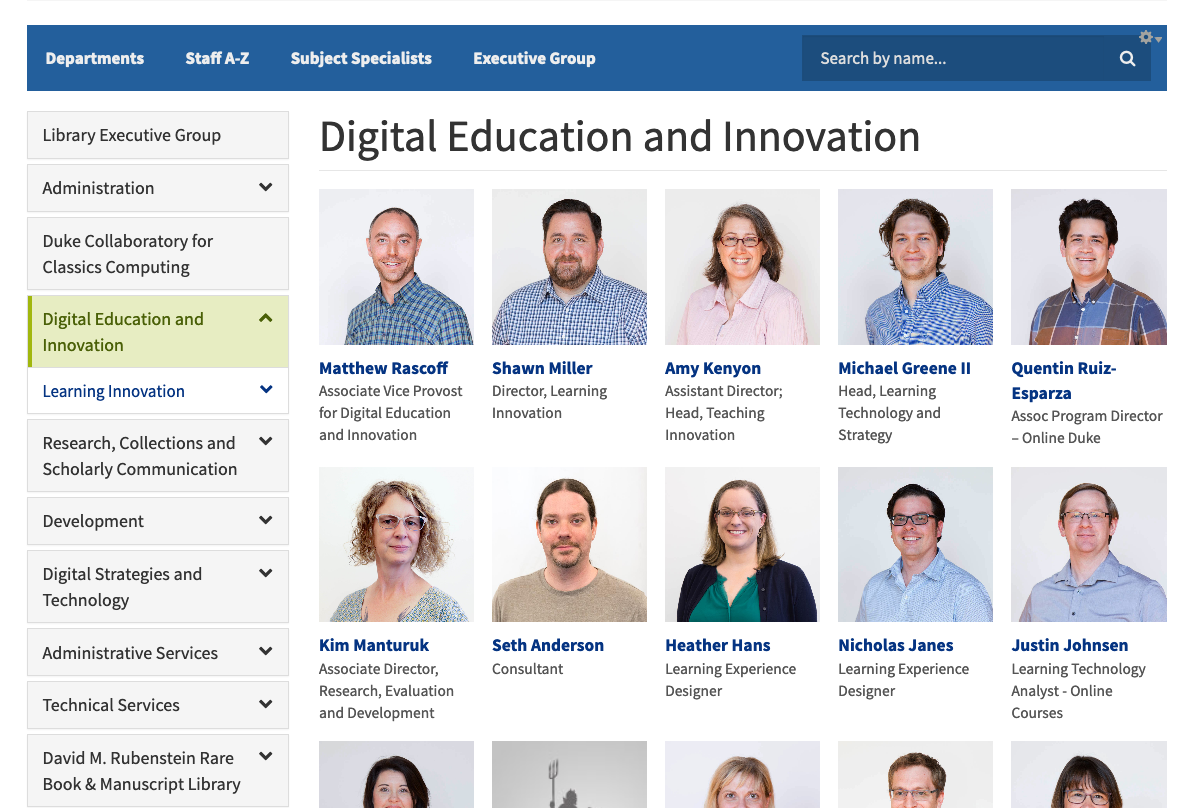

For the past year, developers in the Library’s Software Services department have been working to rebuild Duke’s

For the past year, developers in the Library’s Software Services department have been working to rebuild Duke’s