“Nobody likes you. Everybody hates you. You’re going to lose. Smile, you f*#~.”

Joe Hallenbeck, The Last Boy Scout

While I’m glad not to be living in a Tony Scott movie, on occasion I feel like Bruce Willis’ character near the beginning of “The Last Boy Scout.” Just look at some of the things they say about us.

While I’m glad not to be living in a Tony Scott movie, on occasion I feel like Bruce Willis’ character near the beginning of “The Last Boy Scout.” Just look at some of the things they say about us.

Current online interfaces to primary source materials do not fully meet the needs of even experienced researchers. (DeRidder and Matheny)

The criticism, it cuts deep. But at least they were trying to be gentle, unlike this author:

[I]n use, more often than not, digital library users and digital libraries are in an adversarial position. (Saracevic, p. 9)

That’s gonna leave a mark. Still, it’s the little shots they take, the sidelong jabs, that hurt the most:

The anxiety over “missing something” was quite common across interviews, and historians often attributed this to the lack of comprehensive search tools for primary sources. (Rumer and Schonfeld, p. 16)

I’m fond of saying that the youtube developers have it easy. They support one content type – and until recently, it was Flash, for pete’s sake – minimal metadata, and then what? Comments? Links to some other videos? Wow, that’s complicated.

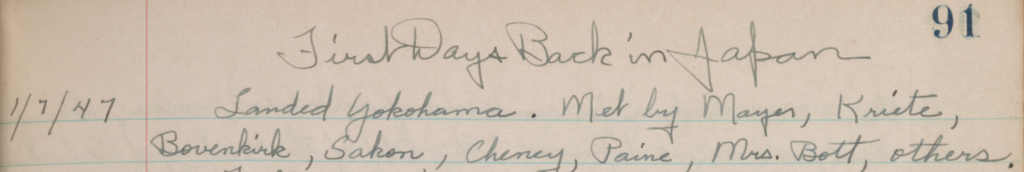

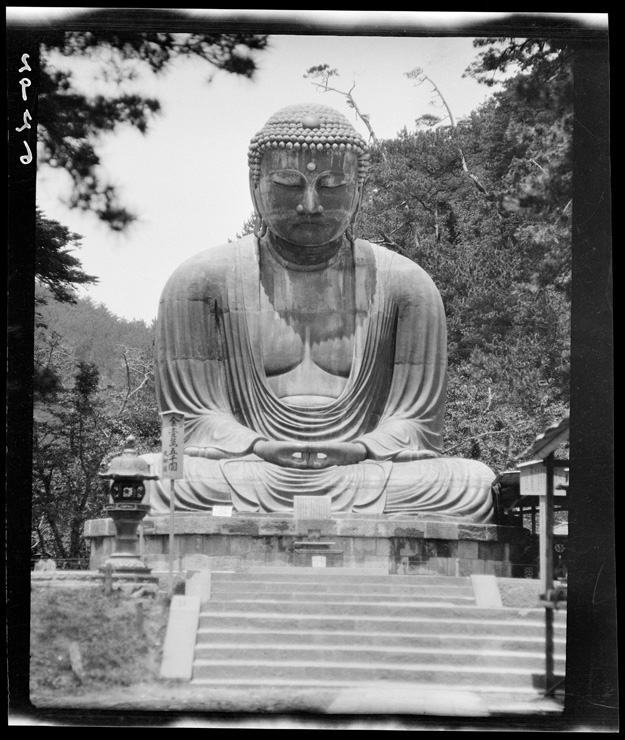

By contrast, we’ve developed for no less than fifteen different item types during the life of Tripod2, the platform that we’ve used to provide discovery and access for Duke Digital Collections since March 2011. You want a challenge? Try building an interface for flippable anatomical fugitive sheets. It’s one thing to create a feature allowing users to embed videos from a flat web-site structure; it’s quite another to allow it from a site loaded with heterogeneous content types, then extend it to include items nested within multiple levels of description in finding aids (for an example, see the “Southwest Georgia Voters Project” item here).

I think the problem set of developing tools for digitized primary sources is one of the most interesting areas in the field of librarianship, and for the digital collections team, it’s one of our favorite areas of work. However, the quotes that open this post (the ones not delivered by Bruce Willis, anyway) are part of a literature that finds significant disparity between the needs of the researchers who form our primary audience and the tools that we – collectively speaking, in the field of digital libraries – have built.

Our team has just begun work on our next-generation platform for digital collections, which we call Tripod3. It will be built on the Fedora/Hydra framework that our Digital Repository Services team is using to develop the Duke Digital Repository. As the project manager, I’m trying to catch up on the recent literature of assessment for digital collections, and consider how we can improve on what we’ve done in the past. It’s one of the main ways we can engage with researchers, as I wrote about in a previous post.

One of the issues we need to address is the problem of archival context. It’s something that the users of digitized primary sources cite again and again in the studies I’ve read. It manifests itself in a few ways, and could be the subject of a lengthier piece, but I think Chassanoff gives a good sense of it in her study (pp. 470-1):

Overall, findings suggest that historians seem to feel most comfortable using digitized sources when an online environment replicates essential attributes found in archives. Materials should be obtained from a reputable repository, and the online finding aid should provide detailed description. Historians want to be able to access the entire collection online and obtain any needed information about an item’s provenance. Indeed, the possibility that certain materials are omitted from an online collection appears to be more of a concern than it is in person at an archives.

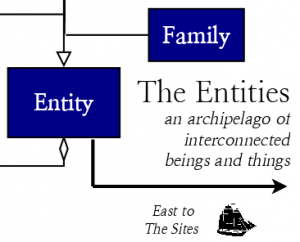

The idea of archival context poses what I think is the central design problem of digital collections. It’s a particular challenge because, while it’s clear that researchers want and require the ability to see an object in its archival context, they also don’t want it. By which I mean, they also want to be able to find everything in the same flat context that everything assumes with a retrieval service like Google.

Archival context implies hierarchy, using the arrangement of the physical materials to order the digital. We were supposed to have broken away from the tyranny of physical arrangement years ago. David Weinberger’s Everything is Miscellaneous trumpeted this change in 2007, and while we had already internalized what he called the “third order of order” by then, it is the unambiguous way of the world now.

With our Tripod2 platform, we built both a shallow “digital collections miscellany” interface at http://library.duke.edu/digitalcollections/, but later started embedding items directly in finding aids. Examples of the latter include the Jazz Loft Project Records and the Alexander Stephens Papers. What we never did was integrate these two modes of publication for digitized primary sources. Items from finding aids do not appear in search results for the main digital collections site, and items on the main site do not generally link back to the finding aid for their parent collection, and not to the series in which they’re arranged.

While I might give us a passing grade for the subject of “Providing archival context,” it wouldn’t be high enough to get us into, say, Duke. I expect this problem to be at the center of our work on the next-generation platform.

Sources

Alexandra Chassanoff, “Historians and the Use of Primary Materials in the Digital Age,” The American Archivist 76, no. 2, 458-480.

Jody L. DeRidder and Kathryn G. Matheny, “What Do Researchers Need? Feedback On Use of Online Primary Source Materials,” D-Lib Magazine 20, no. 7/8, available at http://www.dlib.org/dlib/july14/deridder/07deridder.html

Jennifer Rumer and Roger C. Schonfeld, “Supporting the Changing Research Practices of Historians: Final Report from ITHAKA S+R,” (2012), http://www.sr.ithaka.org/sites/default/files /reports/supporting-the-changing-research-practices-of-historians.pdf.

Tefko Saracevic, “How Were Digital Libraries Evaluated?”, paper first presented at the DELOS WP7 Workshop on the Evaluation of Digital Libraries (2004), available at http://www.scils.rutgers. edu/~tefko/DL_evaluation_LIDA.pdf