(Header image: Illustration by Jørgen Stamp digitalbevaring.dk CC BY 2.5 Denmark)

Here at Duke University Libraries, we often talk about digital preservation as though everyone is familiar with the various corners and implications of the phrase, but “digital preservation” is, in fact, a large and occasionally mystifying topic. What does it mean to “preserve” a digital resource for the long term? What does “the long term” even mean with regard to digital objects? How are libraries engaging in preserving our digital resources? And what are some of the best ways to ensure that your personal documents will be reusable in the future? While the answers to some of these questions are still emerging, the library can help you begin to think about good strategies for keeping your content available to other users over time by highlighting agreed-upon best practices, as well as some of the services we are able to provide to the Duke community.

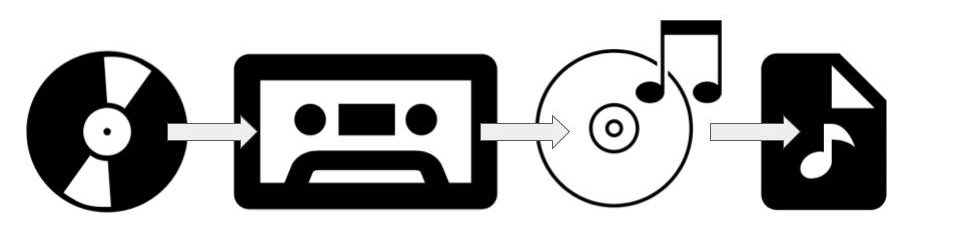

File formats

Not all file formats have proven to be equally robust over time! Have you ever tried to open a document created using a Microsoft Office product from several years ago, only to be greeted with a page full of strangely encoded gibberish? Proprietary software like the products in the Office suite can be convenient and produce polished contemporary documents. But software changes, and there is often no guarantee that the beautifully formatted paper you’ve written using Word will be legible without the appropriate software 5 years down the line. One solution to this problem is to always have a version of that software available to you to use. Libraries are beginning to investigate this strategy (often using a technique called emulation) as an important piece of the digital preservation puzzle. The Emulation as a Service (EaaS) architecture is an emerging tool designed to simplify access to preserved digital assets by allowing end users to interact with the original environments running on different emulators.

An alternative to emulation as a solution is to save your files in a format that can be consumed by different, changing versions of software. Experts at cultural heritage institutions like the Library of Congress and the US National Archives and Records Administration have identified an array of file formats about which they feel some degree of confidence that the software of the future will be able to consume. Formats like plain text or PDFs for textual data, value separated files (like comma-separated values, or CSVs), MP3s and MP4s for audio and video data respectively, and JPEGs for still images have all proven to have some measure of durability as formats. What’s more, they will help to make your content or your data more easily accessible to folks who do not have access to particular kinds of software. It can be helpful to keep these format recommendations in mind when working with your own materials.

File format migration

The formats recommended by the LIbrary of Congress and others have been selected not only because they are interoperable with a wide variety of software applications, but also because they have proven to be relatively stable over time, resisting format obsolescence. The process of moving data from an obsolete format to one that is usable in the present day is known as file format migration or format conversion. Libraries generally have yet to establish scalable strategies for extensive migration of obsolete file formats, though it is generally a subject of some concern.

Here at DUL, we encourage the use of one of these recommended formats for content that is submitted to us for preservation, and will even go so far as to convert your files prior to preservation in one of our repository platforms where possible and when appropriate to do so. This helps us ensure that your data will be usable in the future. What we can’t necessarily promise is that, should you give us content in a file format that isn’t one we recommend, a user who is interested in your materials will be able to read or otherwise use your files ten years from now. For some widely used formats, like MP3 and MP4, staff at the Libraries anticipate developing a strategy for migrating our data from this format, in the event that the format becomes superseded. However, the Libraries do not currently have the staff to monitor and convert rarer, and especially proprietary formats to one that is immediately consumable by contemporary software. The best we can promise is that we are able to deliver to the end users of the future the same digital bits you initially gave to us.

Bit-level preservation

Which brings me to a final component of digital preservation: bit-level preservation. At DUL, we calculate a checksum for each of the files we ingest into any of our preservation repositories. Briefly, a checksum is an algorithmically derived alphanumeric hash that is intended to surface errors that may have been introduced to the file during its transmission or storage. A checksum acts somewhat like a digital fingerprint, and is periodically recalculated for each file in the repository environment by the repository software to ensure that nothing has disrupted the bits that compose each individual file. In the event that the re-calculated checksum does not match the one supplied when the file has been ingested into the repository, we can conclude with some level of certainty that something has gone wrong with the file, and it may be necessary to revert to an earlier version of the data. THe process of generating, regenerating, and cross-checking these checksums is a way to ensure the file fixity, or file integrity, of the digital assets that DUL stewards.