The One Person, One Vote Project is trying to do history a different way. Fifty years ago, young activists in the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee broke open the segregationist south with the help of local leaders. Despite rerouting the trajectories of history, historical actors rarely get to have a say in how their stories are told. Duke and the SNCC Legacy Project are changing that. The documentary website we’re building (One Person, One Vote: The Legacy of SNCC and the Struggle for Voting Right) puts SNCC veterans at the center of narrating their history.

So how does that make the story we tell different? First and foremost, civil rights becomes about grassroots organizing and the hundreds of local individuals who built the movement from the bottom up. Our SNCC partners want to tell a story driven by the whys and hows of history. How did their experiences organizing in southwest Mississippi shape SNCC strategies in southwest Georgia and the Mississippi Delta? Why did SNCC turn to parallel politics in organizing the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party? How did ideas drive the decisions they made and the actions they took?

For the One Person, One Vote site, we’ve been searching for tools that can help us tell this story of ideas, one focused on why SNCC turned to grassroots mobilization and how they organized. In a world where new tools for data visualization, mapping, and digital humanities appear each month, we’ve had plenty of possibilities to choose from. The tools we’ve gravitated towards have some common traits; they all let us tell multi-layered narratives and bring them to life with video clips, photographs, documents, and music. Here are a couple we’ve found:

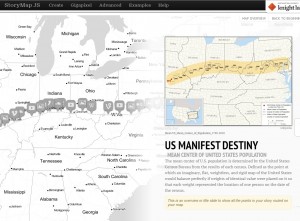

StoryMap: Knightlab’s StoryMap tool is great for telling stories. But better yet, StoryMap lets us illustrate how stories unfold over time and space. Each slide in a StoryMap is grounded with a date and a place. Within the slides, creators can embed videos and images and explain the significance of a particular place with text. Unlike other mapping tools, StoryMaps progress linearly; one slide follows another in a sequence, and viewers click through a particular path. In terms of SNCC, StoryMaps give us the opportunity to trace how SNCC formed out of the Greensboro sit-ins, adopted a strategy of jail-no-bail in Rock Hill, SC, picked up the Freedom Rides down to Jackson, Mississippi, and then started organizing its first voter registration campaign in McComb, Mississippi.

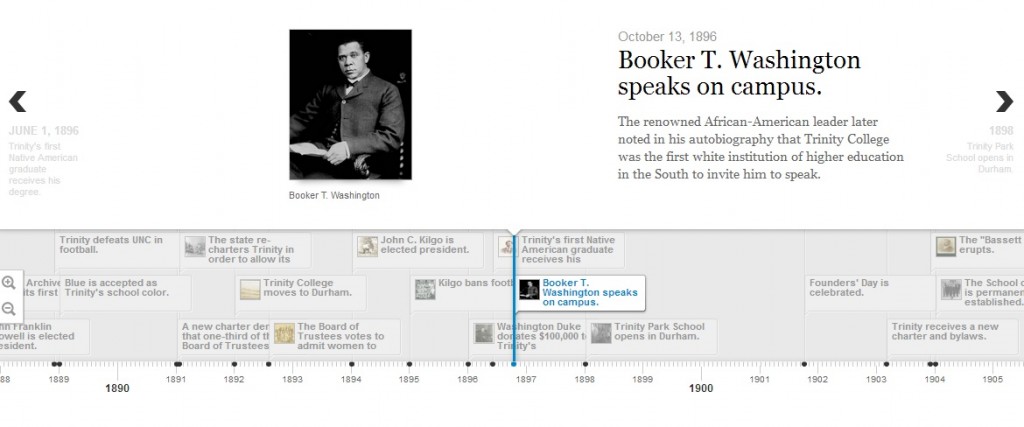

Timeline.JS: We wanted timelines in the One Person, One Vote site to trace significant events in SNCC’s history but also to illustrate how SNCC’s experiences on the ground transformed their thinking, organizing, and acting. Timeline.JS, another Knightlab tool, provides the flexibility to tell overlapping stories in clean, understandable manner. Markers in Timeline.JS let us embed videos, maps, and photos, cite where they come from, and explain their significance. Different tracks on the timeline give us the option of categorizing events into geographic regions, modes of organizing, or evolving ideas.

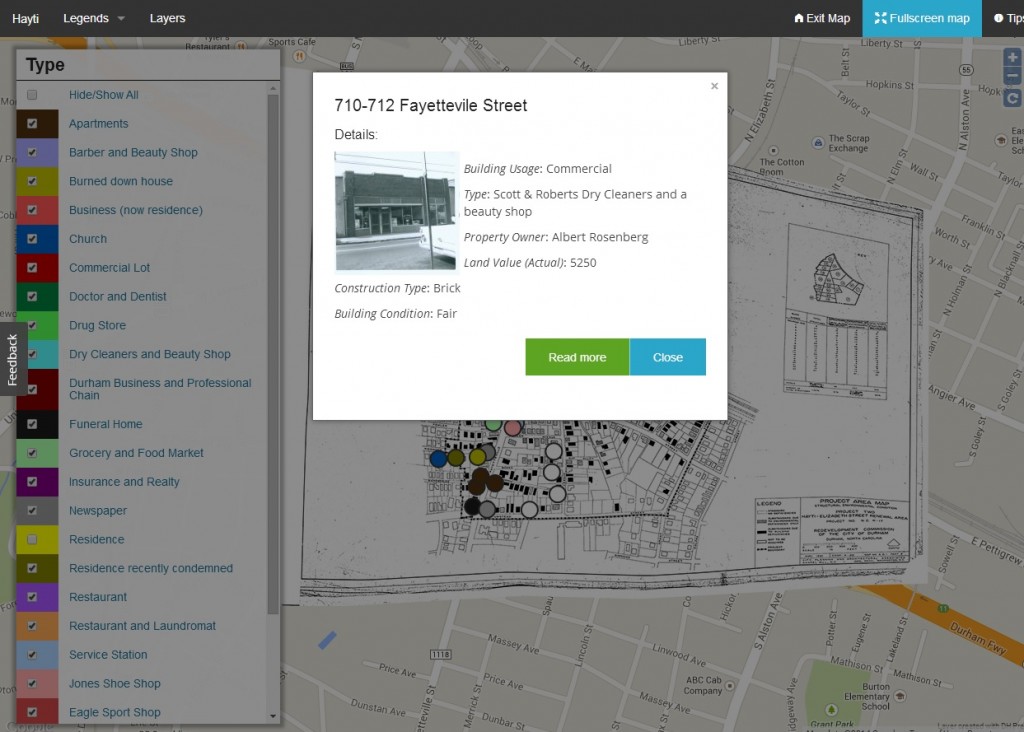

DH Press: Many of the mapping tools we checked out relied on number-heavy data sets, for example those comparing how many robberies took place on the corners of different city blocks. Data sets for One Person, One Vote come mostly in the form of people, places, and stories. We needed a tool that let us bring together events and relevant multimedia material and primary sources and represent them on a map. After checking out a variety of mapping tools, we found that DH Press served many of our needs.

Coming out of the University of North Carolina – Chapel Hill’s Digital Innovation Lab, DH Press is a WordPress plugin designed specifically with digital humanities projects in mind. While numerous tools can plot events on a map, DH Press markers provide depth. We can embed the video of an oral history interview and have a transcript running simultaneously as it plays. A marker might include a detailed story about an event, and chronicle all of the people who were there. Additionally, we can customize the map legends to generate different spatial representations of our data.

These are some of the digital tools we’ve found that let us tell civil rights history through stories and ideas. And the search continues on.

May I caution you a bit in your conclusions as to inclusivity? “… puts SNCC veterans at the center of narrating their history …” – this assumes, a) that you find all the “drivers” (were they still alive) and could interview them and b) that they will narrate truthfully AND/OR do fully and truthfully remeber the happenings “back when”. Now, as for a): if you had been an anti-nuclear activist in France in the 1970s, you would probably not (all) be known publicly -for someone like you to find them later- as France has a legal framework in place whereby the nuclear industry, tied to nuclear armament, is a state secret. Even journalists can get persecuted for reporting. So in all probability, you will never find public records about the the “real”, the “effective” activists and hence will never be able to attribute their successes or failures to them. But rather you may fall victim to attribute obvious success to someone else, interview them and find that bias corroborated … As for b): some of the activists did things, even with the best of intentions, that might still be a punishable offense now as the statute of limitations may not have run out. It is unlikely you could interview them. Had Angela Davis, for whose release I back then campaigned in Europe, not bee in jail on trial for murder charges, but were today still in hiding, again, you would not interview her, she would not be found under her real name and she would not dare participate in such a project for fear of “rejuvenating” the efforts to search for her. It is my sincere conviction that, how much we may try, with radical political movements the history will always be a deceptive patchwork and many of the true “heroes” will never be given their full credits.