As much myth as morsel, the traditional southern dish of black-eyed peas, long-grain rice and salt pork–known as Hoppin’ John—has long been associated with good fortune when eaten on the first day of the new year.

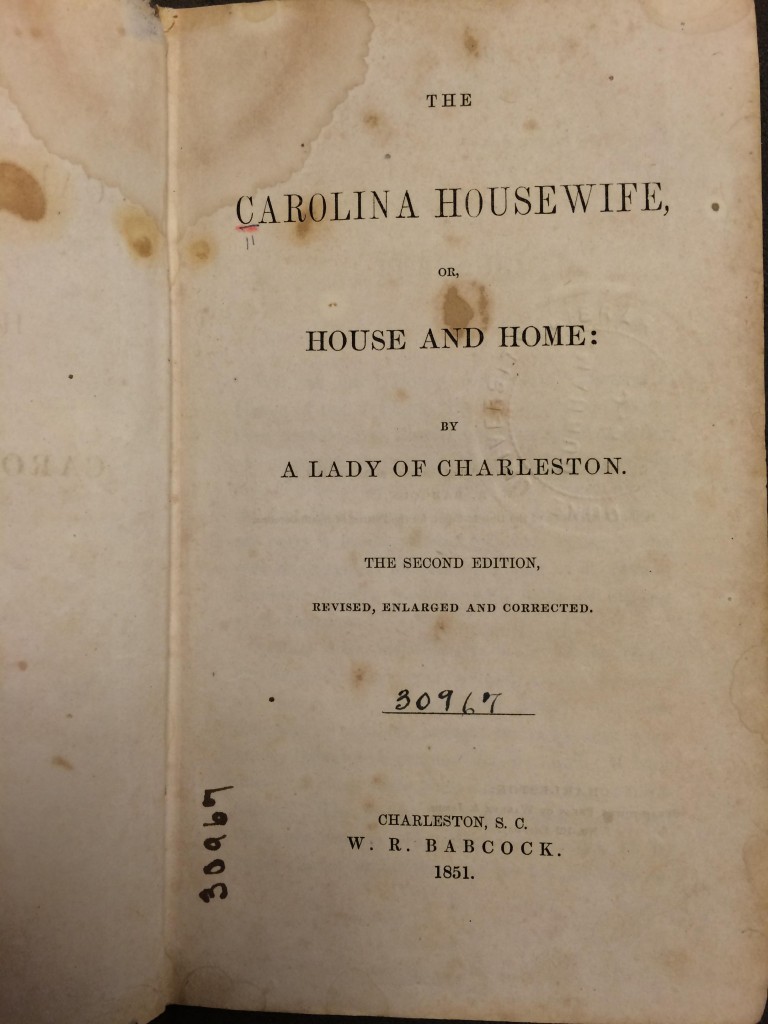

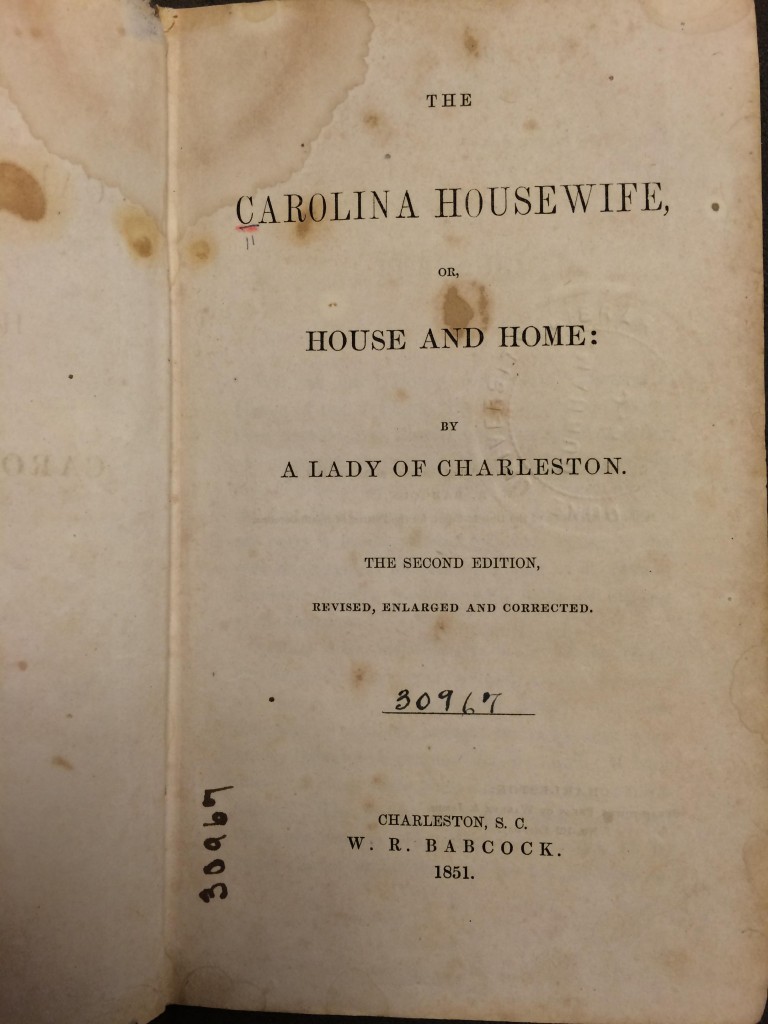

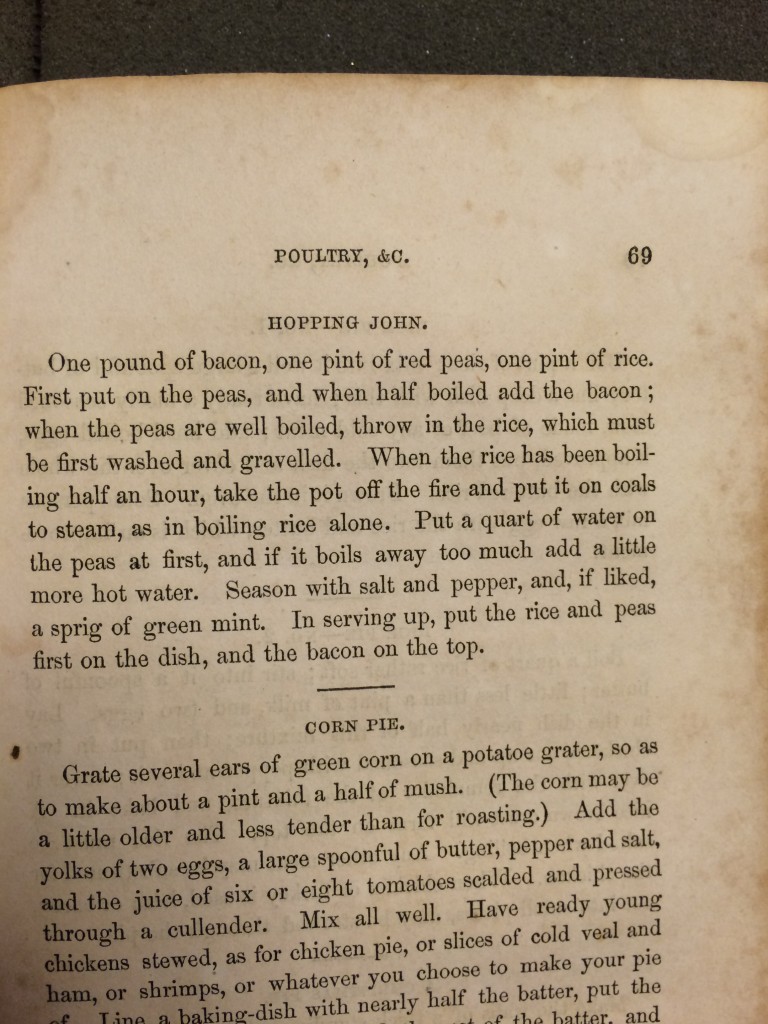

With January 1st fast approaching, I thought I would use the test-kitchen blog to try out the earliest known published recipe for Hoppin’ John, which comes from Sarah Rutledge’s The Carolina Housewife, originally published in 1847.

But like any good legume dish, half of the work lies in letting the beans soak, so before I get into the recipe itself, I want to spend a little time soaking up the aura of this deceptively simple meal.

Google the term Hoppin’ John, with or without the conspicuous g-deletion, and you’ll find a veritable cottage industry of food historians contemplating its finer points. While rice and pork are essential features of Hoppin’ John, most commentators center their accounts on the black-eyed pea, known variously as the cow pea, crowder pea and southern pea. Native to West Africa, the black eyed-pea was cultivated throughout the ancient world, from Greece and Rome to the Middle East and Asia. The durability of the dried African bean made it a prime provision aboard the transatlantic slave ship. The hardiness of the plant and its resistance to heat made it a staple crop on southern plantations, where it became a cheap and reliable means of feeding slaves and livestock. Poor whites across the south embraced the food, and in time, it eventually appeared on the table of southern planters, where it was received as a “very nutritious” and “quite healthy” alternative to the English field pea. Despite attempts on the part of the U.S. Department of Agriculture to expand the crop beyond the Mason-Dixon line after WWI, the food has remained part of the often-caricatured culture of the American South.

And this is to say nothing about the black-eyed pea as prosperity charm or the twisted narrative behind the name Hoppin’ John. In the context of ancient Greece and Egypt, beans were said to possess the spiritual energy of the dead. Whether or not this has any bearing on the America tradition of eating black-eyed peas for good luck is impossible to know. A popular theory as to why the food must be eaten on New Year’s Day revolves around the supposed resemblance of the spotted pods to coins. Similar theories hold that collard greens, often served alongside black-eyed peas, represented paper money. Having grown up in a Tennessee household that regularly consumed black-eyed peas, I called my mother and asked her what she thought. Timid when questioned, she only said: “On New Year’s Day, it didn’t matter what else you had, as long as you had black-eyed peas.” She has a point. It makes sense for the working poor and enslaved to project mythical powers onto the foodstuff that was a ubiquitous part of their everyday lives. When life seems little more than a series of uncontrollable events, strung together by forced migration, famine and persecution, you don’t want to leave matters of good fortune to chance. Or as my mother says, “You don’t go borrowing problems.”

As for the name Hoppin’ John, there is no definitive etymology. Some researchers focus on the semantic meaning of the term, suggesting that it grew out of a folk idiom for inviting a neighbor to dinner, i.e. Hop in John. Others focus on the phonetic properties of the term, insisting that it is an English appropriation of either a French-Haitian name for the pigeon pea (pois à pigeon) or the Arabic name for a similar dish of beans and rice (bahatta kachang). For me, I think the mystery of the name points back to that essential feature of vernacular culture that Richard Wright proposes in his essay “The Literature of the Negro in the United States,” where he describes black folklore and folkways as “The Form of Things Unknown.” By positing unknowing and mystery as the basis of vernacular culture, one is able to entertain various, competing theories while maintaining a healthy respect for the hermetic resistance of anonymous practices.

These various theories were debated in real-time as Ashley Young (Duke, History PhD) and Lin Ong (Duke, Marketing Strategy PhD) helped me bring Rutledge’s recipe for Hoppin’ John to life.

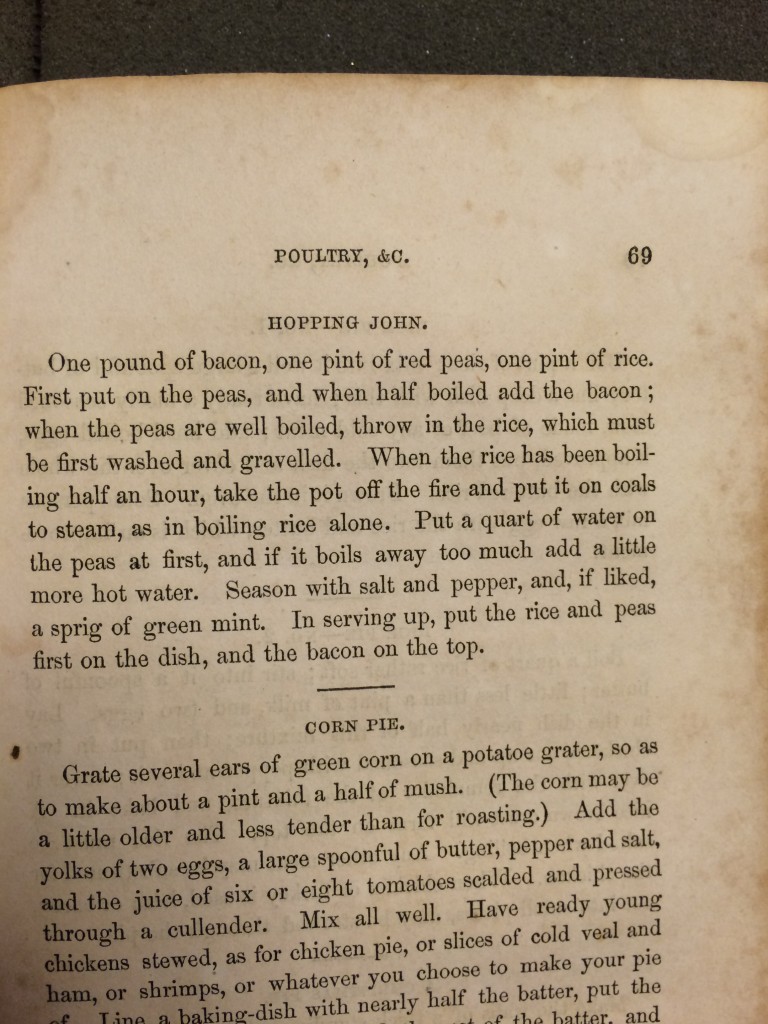

The original recipe is short on details. Here it is in its entirety:

Given the ambiguity of the description and the dramatic changes affecting cultivation and cooking practices, the recipe requires a certain amount of creativity. The cowpeas that Rutledge mentions are prevalent in most parts of the rural south, but I could not find a local store in Durham that carried them in December, so I settled for the black-eyed cousin. As for the rice, I went with Luquire Family Food’s Long Grain Rice on the suggestion of Ashley, a food historian with an eye for unpolished grains. Instead of the standard cured bacon, I decided to go with a medley of swine. A hamhock would provide ample seasoning and flavor, while pieces of pork belly would give a little meat for the actual dish. Lin made the important point that the pork belly would probably take on an unappealing texture if cooked in the boiling stew. So we sliced the pound of pork belly into 1-inch cubes and pan-fried the cubes, adding them (along with a spoonful of the rendering) to the dish at the end.

To speed up the cooking time, I soaked the pint of beans by bringing them to boil in a quart of water, letting them boil for a minute and then leaving them to cool for an hour. We then transferred the beans into a new pot with a fresh quart of water and the hamhock. We brought the stew to a boil and then let it simmer for close to an hour. While the beans were cooking, we washed the rice, making sure to remove all pieces of gravel, as per Rutledge’s slightly outdated instructions. With no objective way of determining when the beans were “half-boiled,” we settled on an hour. In that amount of time there was still enough water in the pot to cook the rice. But this seems totally arbitrary. If you like mushy beans (which I do), don’t be afraid of cooking them longer. You can always add more water when it comes time to cook the rice.

Instead of just placing sprigs of mint on top like a garnish, we decided to slice them into shreds to help bring out the flavor. The experiment paid off. The sharp soprano sweetness of the herb cut against the walking bass notes of the simple grain and savory fat. The end result was a meal that made us feel plenty lucky, if only to have leftovers to go around.

Instead of just placing sprigs of mint on top like a garnish, we decided to slice them into shreds to help bring out the flavor. The experiment paid off. The sharp soprano sweetness of the herb cut against the walking bass notes of the simple grain and savory fat. The end result was a meal that made us feel plenty lucky, if only to have leftovers to go around.

Notes

One could spend an entire day reading through the many, thoughtfully composed online histories of Hoppin’ John. Most of the points made in these posts can be traced back to two works.

Miller, Adrian. Soul Food: The Surprising Story of an American Cuisine, One Plate at a Time. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2013.

Hess, Karen. The Carolina Rice Kitchen: The African Connection. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1998.

Post contributed by Pete Moore, Intern for the Hartman Center for Sales, Advertising, and Marketing History

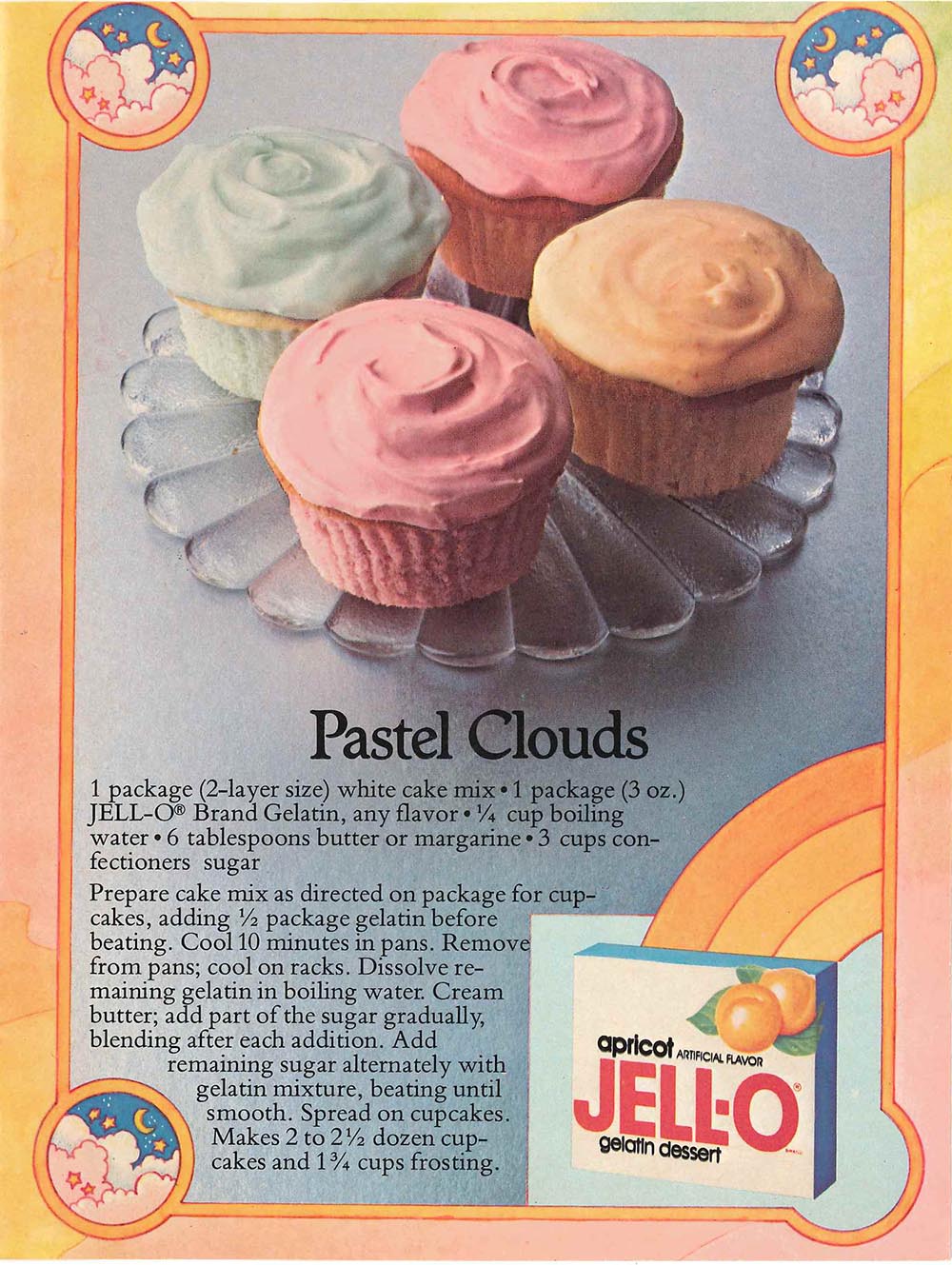

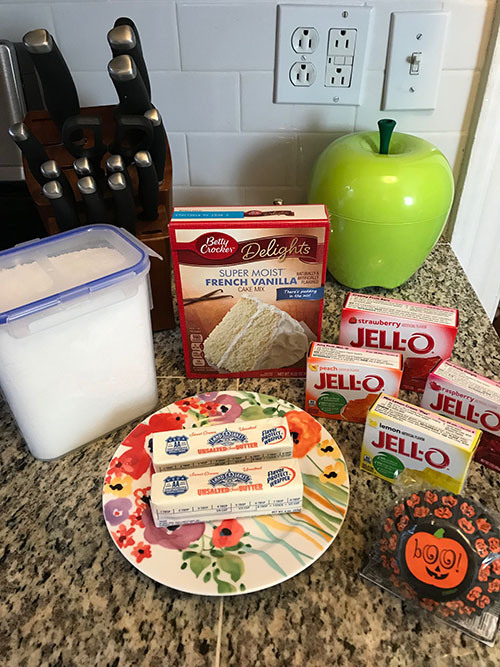

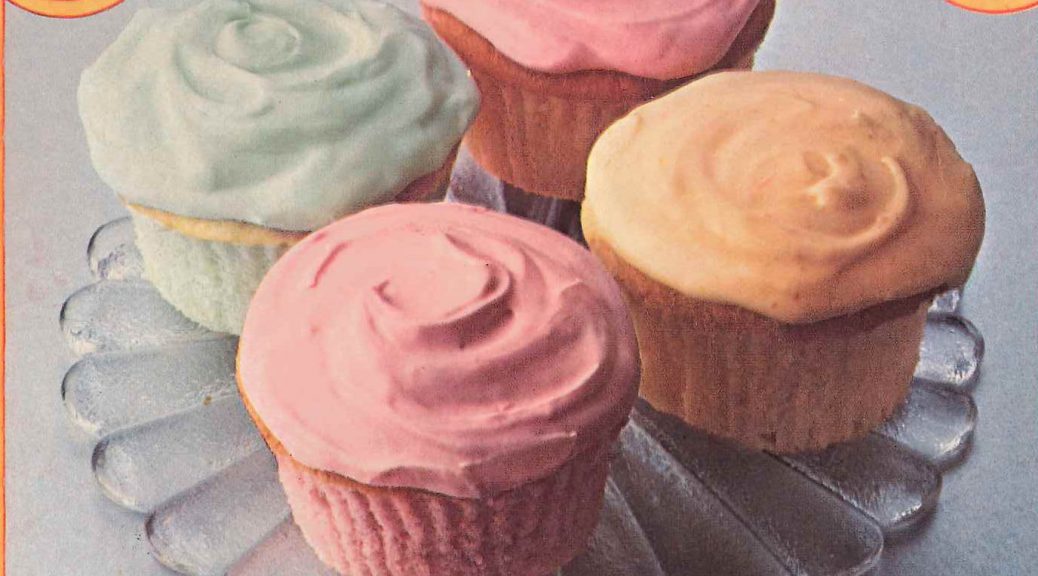

I have not visited the Jell-O section of a grocery store in many years and . . . there are so many flavors of Jell-O! I may have gone a little overboard: I got strawberry, raspberry, lemon, and peach and decided I’d make strawberry cupcakes with lemon icing and peach cupcakes with raspberry icing. Which, since I planned to make only one batch of cupcakes, meant dividing lots of things in half, but I managed. And it’s finally October, so I also had a chance to use my spooky Halloween baking cups (which might not fit with the “pastel clouds” vibe, but oh well).

I have not visited the Jell-O section of a grocery store in many years and . . . there are so many flavors of Jell-O! I may have gone a little overboard: I got strawberry, raspberry, lemon, and peach and decided I’d make strawberry cupcakes with lemon icing and peach cupcakes with raspberry icing. Which, since I planned to make only one batch of cupcakes, meant dividing lots of things in half, but I managed. And it’s finally October, so I also had a chance to use my spooky Halloween baking cups (which might not fit with the “pastel clouds” vibe, but oh well).

Instead of just placing sprigs of mint on top like a garnish, we decided to slice them into shreds to help bring out the flavor. The experiment paid off. The sharp soprano sweetness of the herb cut against the walking bass notes of the simple grain and savory fat. The end result was a meal that made us feel plenty lucky, if only to have leftovers to go around.

Instead of just placing sprigs of mint on top like a garnish, we decided to slice them into shreds to help bring out the flavor. The experiment paid off. The sharp soprano sweetness of the herb cut against the walking bass notes of the simple grain and savory fat. The end result was a meal that made us feel plenty lucky, if only to have leftovers to go around.

A manuscript (i.e. handwritten) cookbook can tell us a great deal about its creator. What foods were available to her? How would her family have celebrated holidays and birthdays? Was she an elite woman with a cook who could prepare elaborate dishes, or a farm wife who had to prepare simple, hearty fare and preserve her harvest to feed her family? Do the recipes reflect a particular ethnic or religious background or geographical location? As is the case today, routine meals do not require a recipe. It is the special occasion recipes, especially those that require careful measurements to work properly, that are recorded for future reference.

A manuscript (i.e. handwritten) cookbook can tell us a great deal about its creator. What foods were available to her? How would her family have celebrated holidays and birthdays? Was she an elite woman with a cook who could prepare elaborate dishes, or a farm wife who had to prepare simple, hearty fare and preserve her harvest to feed her family? Do the recipes reflect a particular ethnic or religious background or geographical location? As is the case today, routine meals do not require a recipe. It is the special occasion recipes, especially those that require careful measurements to work properly, that are recorded for future reference.