Anyone reading this blog knows that archives are full of wonderfully weird ephemera just waiting to be discovered and discussed, of conversations waiting to happen. This is the story of two archives that, it turns out, have a lot to talk about.

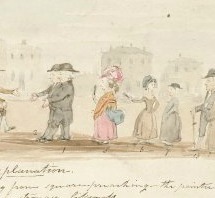

The John Rylands University Library at the University of Manchester has had this drawing on its webpage for some time:

Ostensibly, this is a doodle, maybe an early comic. It depicts an ordinary meeting between preachers and parishioners. Only one thing stands out: the stocky girl just off the center dressed in bright pink and orange, while everyone around her wears drab brown. Look closer and you see that she her awkwardness is not limited to her dress: oblivious to the women gossiping behind her, our young heroine “stands, patiently, while her papa shakes hands with all the colliers, not knowing but she must do so too – a perfect pattern! Dear lady!” This oblivious fool is also the artist.

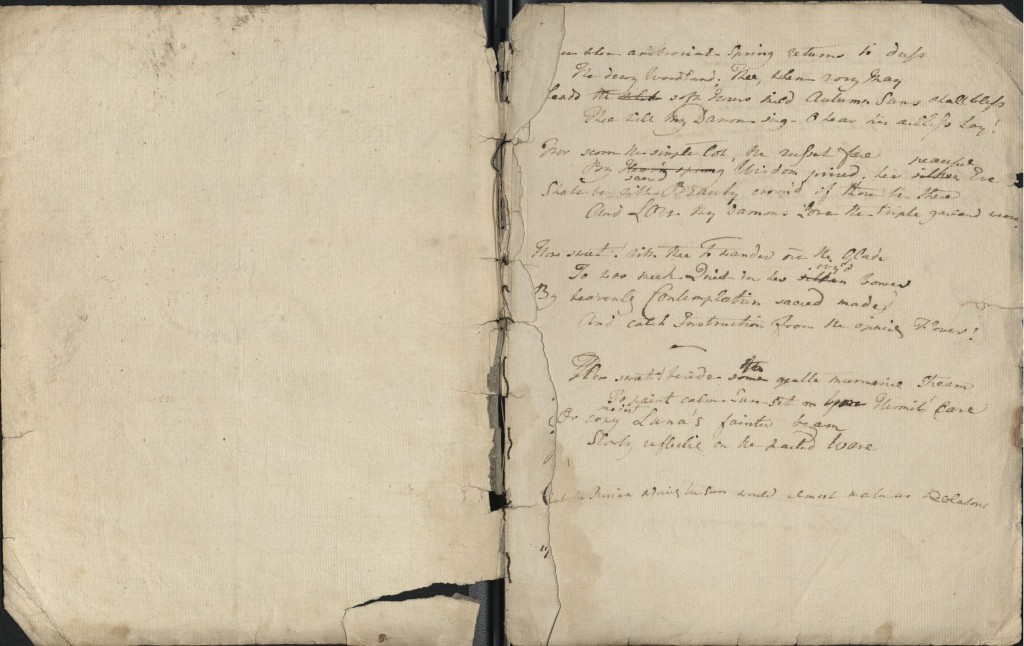

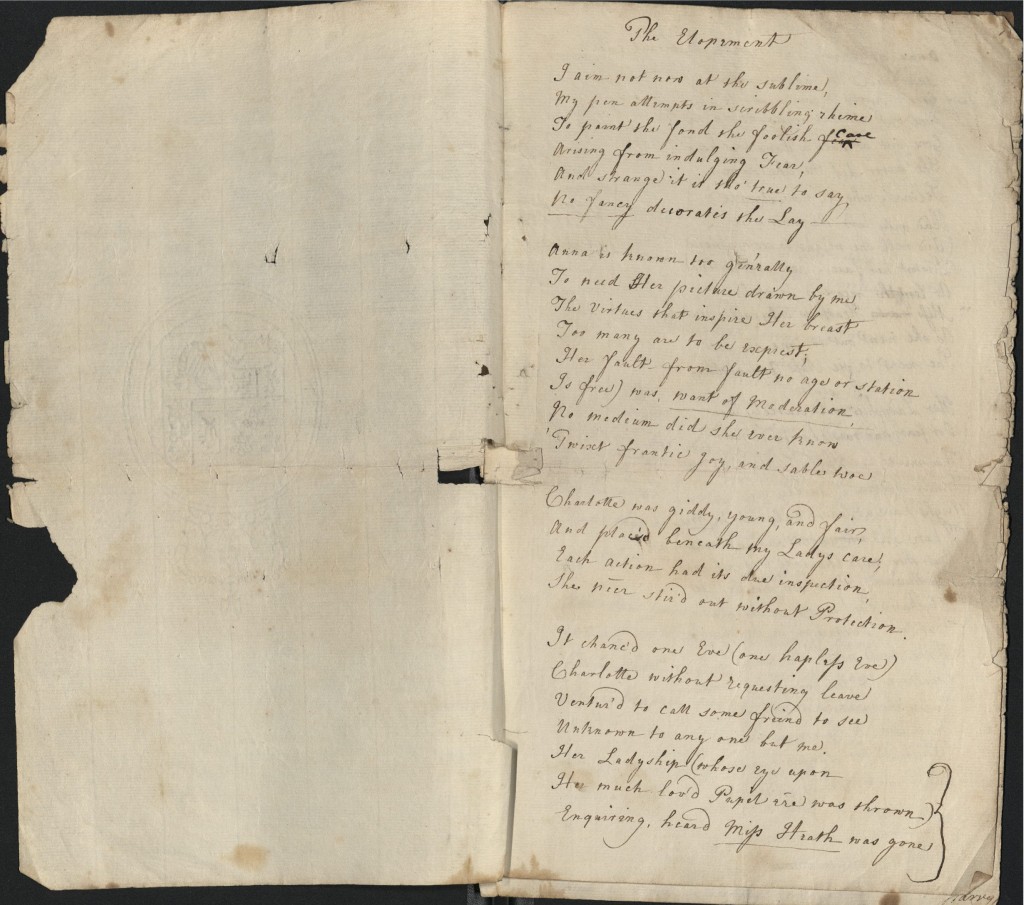

Cut to our own archive: Two summers ago, I was working in the Frank Baker Collection of Wesleyana and British Methodism when I came upon some poems. Having cataloged plenty of manuscript materials within the collection, I wouldn’t have thought much of them, except I noticed that they were tied together with string. Fanciful English student that I am, I recalled that Emily Dickinson’s manuscripts had been likewise fashioned together, and so began my grandiose visions: had I stumbled upon the British Emily? Could these poems help to reinvigorate the field of 18th-century women’s poetry – revolutionize it, even? It’s the fantasy held dear by every budding academic: to discover the next Milton or Frost, to shake the scholarly world to its core. Needless to say, literary scholarship remains unshaken, but it does have a new name on its register: Sarah Wesley.

The poems I found were written by our pink-and-orange artiste, the daughter of Charles Wesley, a co-founder of British Methodism. What is so fascinating about Sarah Wesley is her outright resistance to the restrictive practices of her every-day life – and how, perhaps as a result of that resistance, she has since all but disappeared from most histories of British Methodism.

Her poetry in particular served as an outlet for questioning her father’s religion, as well as engaging with emergent conversations about the rights of women. Even while Wesley’s social commitments were progressive, she remained a devout Methodist throughout her life. But through her writing, most of which she kept hidden away from the judgmental eyes of her community, Wesley takes us to a place we don’t often think of when we read the eighteenth century: the private mind of the teenage girl.

Caitlin Flanagan’s recent book Girl Land (Little, Brown and Co., 2012) makes a compelling case for the fundamental significance of a particular marker of female adolescence: that time when a girl recedes into her room for a few years and emerges a brooding melodramatic for a few more. Flanagan posits that as a society, we take too lightly “a girl’s sudden need to withdraw from the world for a while and inhabit a secret emotional life” (1). But in fact, this is time and space that young girls need in order to come to terms with the world and their place within it. And so, Flanagan urges us to celebrate, rather than denigrate, the importance of this space she calls “girl land.”

Flanagan’s study is predicated on a particular reading of the history of the teenager. But even before “adolescence” became a discrete intellectual category in the twentieth century, Sarah Wesley was, in many ways, a typically modern teenage girl.

She wrote poetry that was evocative, romantic, and highly self-reflexive:

The Pilot Reason stays on Shore,

The boisr’ous Passions more,

Youth is the Ship and Hope the Oar,

And O! the Sea is Love!

~from “Sonnet,” 1770

In particular, much of her work is preoccupied with exploring her budding sexuality:

Her Eyes enraptur’d shall your Beauties own

Her snowy Fingers be your Virgin Lone!

Her Lips shall bid Thee with a sigh Adieu!

Her Lips shall greet Thee with ambrosial Dew!

Descending showers shall fall from Heaven to gaze!

Within your silken Folds shall Graces lie

And panting Zephryss on your Bosom die!

The Muse shall stamp Thee with Idalia’s Crest,

And Venus court Thee to adorn her Breast.

~from “On receiving a Nosegay,” n.d.

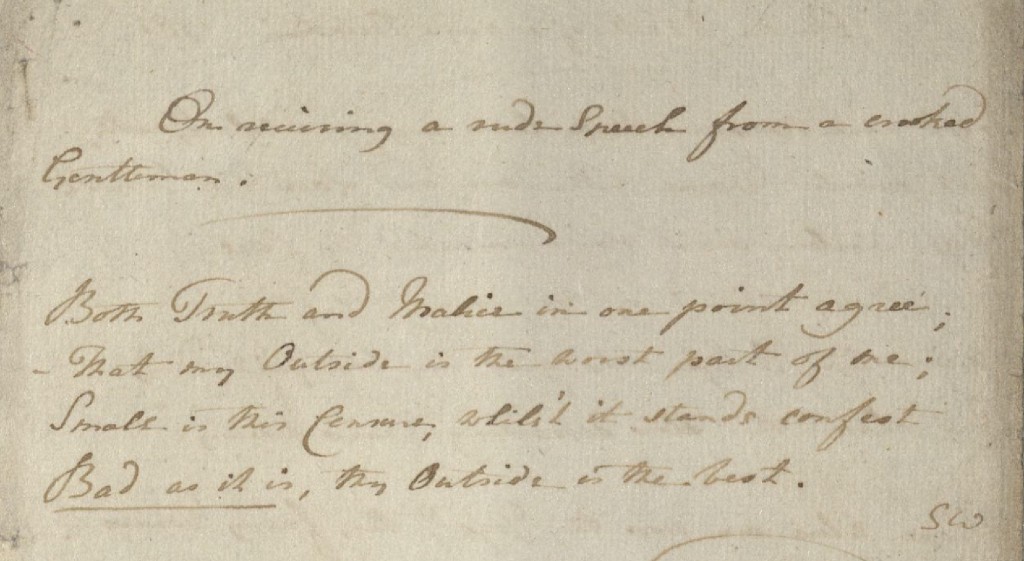

However, she was not without some snark when it came to matters of romance:

Both Truth and Malice on one point agree

That my outside is the worst part of me

Small is the censure, whilst it stands confest

Bad as it is, thy outside is the Best!

~“Epigram: on receiving a rude Speech from a Crooked Gentleman,” 1777

As we saw in the drawing from the Manchester archive, she held some anxiety over her appearance and the perceptions of others.

And in perhaps the defining feature of “girl land,” she was adamant about challenging the values she inherited from her family in order to come to her own understanding of her world (for more on the particulars of Wesley’s intellectual rebellion, see my essay in the Winter 2013 volume of Eighteenth-Century Studies, which expounds on her feminist and abolitionist interests).

So did my work in the Frank Baker Collection yield the next Emily Dickinson? Not exactly. At the level of versification, Wesley’s poetry is derivative at best. But in the connections she asks us to draw between religion and the secular discourses of the key social issues at the end of the eighteenth century, Wesley’s voice raises many productive questions, which I hope eighteenth-century scholars will continue to engage. And further still, the familiar tenor of her poetry demonstrates the persistence of “girl land,” and how productive that sometimes alien-seeming place can be.

Post contributed by Deanna Koretsky, a Ph.D. candidate in the Duke English Dept. and a graduate student assistant in Technical Services.